During the 1840s, the Hawaiian government continued to reorganize, establishing departments and administrative structures. Key issues included securing recognition internationally and addressing land ownership in Hawai‘i. At the same time, Hawaiians protested the growing dominance of foreigners in government and feared the government’s rapid move to adopt private-land ownership. Perspectives differed widely on the evolving path of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i.

Formalizing the Government

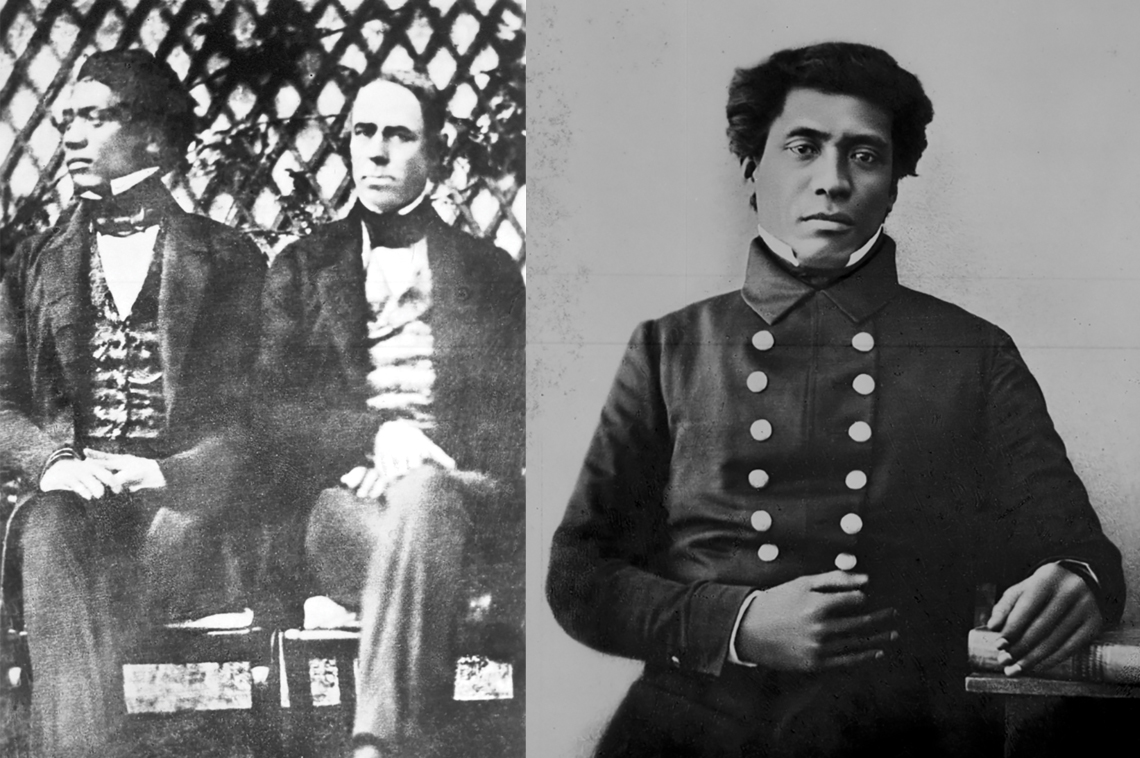

- In 1842, the National Treasury Board was established. The king appointed Dr. Gerrit Judd,1 Timothy Ha‘alilio and John ‘Ī‘ī as members, charging them with organizing the kingdom’s accounts and settling its debts.

- American John Ricord was appointed Hawai‘i’s first attorney-general in 1844. On his advice, the ali‘i adopted legal traditions from Britain and America, which led to the Organic Acts of 1845 – 1847. These established executive departments and the Privy Council, defined the duties of island governors and further organized the judiciary. Significantly, the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles was also created to resolve land-tenure claims.

- On May 20, 1845, the legislature opened in Honolulu for the first time, with great fanfare, formalizing a representative government “common to all liberal and enlightened governments.”2

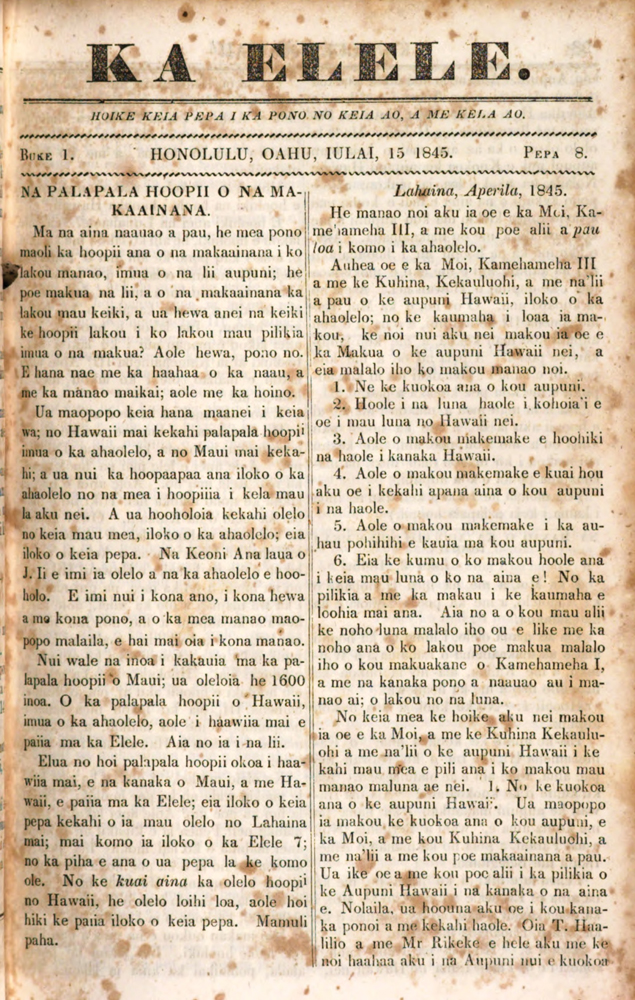

- Hawaiians protested the dominance of foreigners in government. These took the form of prayer meetings, letters published in Ka Elele newspaper and petitions to the king and legislature: “If this kingdom is to be ours, what is the good of filling the land with foreigners?”3

— Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa, Native Land and Foreign Desires, p. 181

International Relations

- Following the enactment of the Bill of Rights and Constitution, “it was necessary, for the future security of the kingdom, to have its independence placed upon the solid basis of a formal recognition by the great powers.”4

- In July 1842, William Richards and Timothy Ha‘alilio were sent as envoys of the king to visit Washington, D.C., France and Great Britain, and “secure the acknowledgement by those governments of the independence of this nation.”5

- In March 1845, Richards returned with proclamations from Britain, France, America and Belgium that officially recognized Hawai‘i’s independence. Richards returned alone as Ha‘alilio had died on the return journey.

Land Ownership

- Governmental reform was accompanied by a revolution in land. The Constitution declared that while all land belonged to Kamehameha, it was not his private property but rather belonged to the chiefs and people in common, of whom Kamehameha was the head.

- Foreigners, both those seeking economic opportunities and missionaries, advocating for commoners’ rights, continued to pressure the government to adopt Western norms of land ownership. Many chiefs supported this, as they had been making land “agreements” for economic purposes.

- From 1845 – 1850, the king’s Privy Council established a series of committees and adopted a process to divide up the lands, which had been owned in common.

- The Māhele of 1848 documented the division of lands agreed among the king and 240 chiefs and konohiki. It defined the Crown lands, held by the king individually; the Government lands, given by the king to the government; and the Chief/Konohiki lands.

- All lands were “subject to the rights of native tenants” and the Kuleana Act of 1850 detailed the process for these claimants, formalizing the Kuleana lands.

- While initially prohibiting aliens from acquiring land, pressure by chiefs and foreigners led to the Resident Alien Act of 1850, which ended such restrictions subject to the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- This rapid change addressed many cultural misunderstandings about land “agreements” but was confusing and disruptive, particularly for the maka‘āinana. The Māhele remains one of the most controversial decisions of Kauikeaouli’s reign.

— Dr. Dwight Baldwin, missionary on Maui, writing to William Richards, June 3, 18476

— Sarah Vowell, Unfamiliar Fishes, p. 157, quoting John H. Chambers

Voices of Resistance

- Hawaiians raised their concerns about the changes. Petitions were submitted from all islands, with hundreds to thousands of signatures.

— A Petition to Your Gracious Majesty Kamehameha III, and to all your Chiefs in Council Assembled, English translation, Friend, Aug. 11, 1845, p. 1187

— Petition printed in Hawaiian in Ka Elele Hawai‘i, English translation in The Polynesian, August 9, 1845

— Samuel M. Kamakau letter to Kauikeaouli, July 22, 1845, describing his conversation with elders, Ruling Chiefs of Hawai‘i, pp. 400 – 401

Even today, widely divergent views abound about the impact of foreign pressures, the bias of naturalized citizens, choices made by the government and the independence of those choices, as the Kingdom of Hawai‘i navigated the nineteenth century.

1 Note that foreigners appointed to government positions were required to take an oath of allegiance to Kamehameha III and renounce allegiance to their home country.

2 Polynesian, May 24, 1845.

3 Petition quoted in Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom 1778 – 1854 Revised, p. 259.

4 Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, p. 187.

5 Letter from Kamehameha III to Sir George Simpson and William Richards, April 8, 1842, quoted in Kuykendall, p. 192.

6 Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, p. 265.

7 Original Hawaiian language petition was called “Na Palapala Hoopii O Na Makaainana” (Petitions of the Maka‘āinana), printed July 1845, in Ka Elele newspaper.