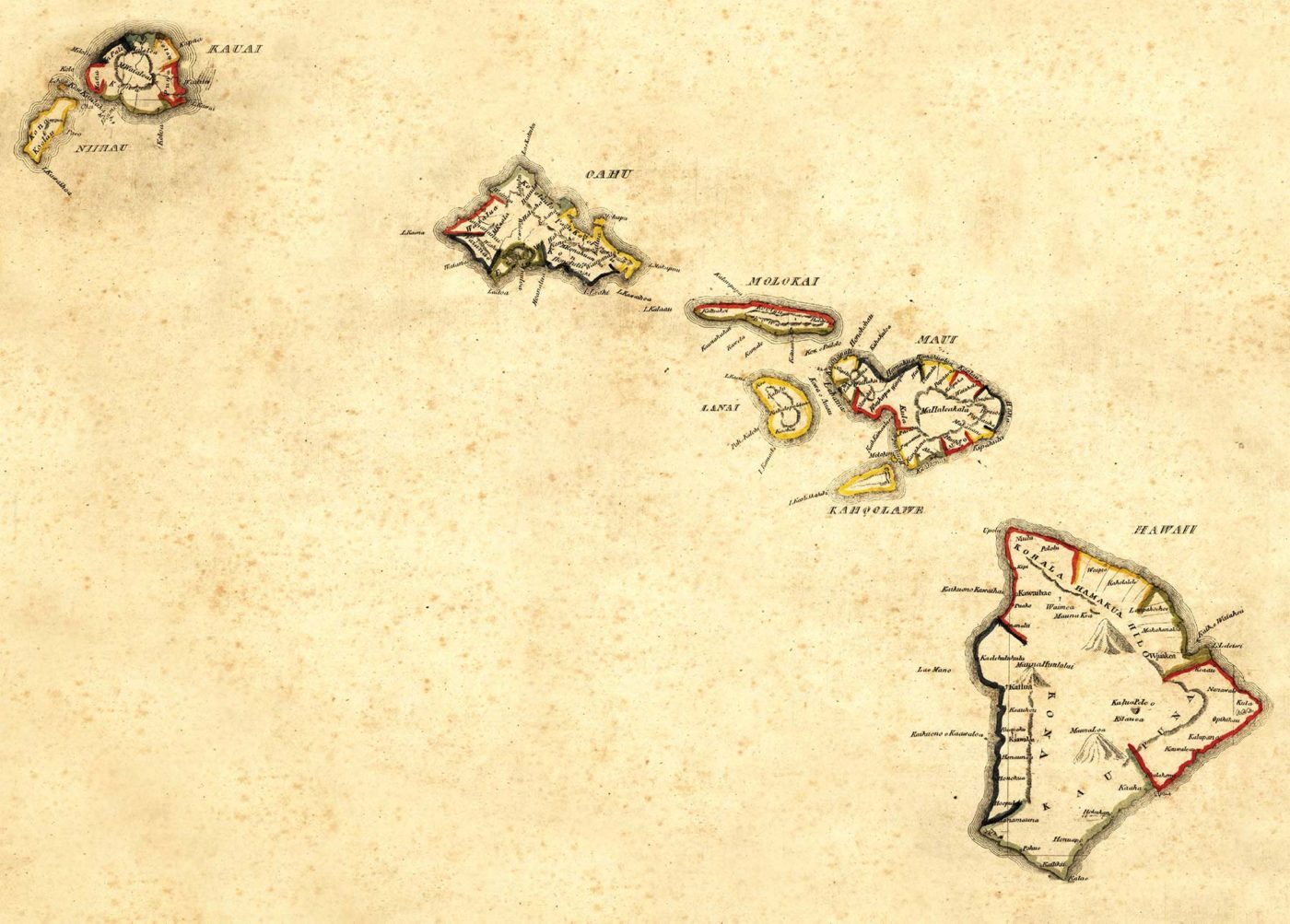

Around 1,000 years ago,1 navigators from the Marquesas Islands launched an unprecedented voyage of discovery across the Pacific Ocean. Steering hand-hewn canoes across 2,000 miles of uncharted seas, guided by stars, ocean swells, birds, and cloud formations, they found one of the most remote archipelagos on Earth – the Hawaiian Islands.

Stepping onto land, the explorers encountered an array of natural wonders. Hawai‘i’s geographic isolation had created a cradle of evolution, where endemic plants and animals proliferated on each of the major islands. At one time, Hawai‘i had 851 species of endemic flowering plants, including six native sandalwood trees; 752 species of land snails; and 71 species of birds, all of which could be found nowhere else in the world.2 Amid a largely predator-free environment, species often shed their natural defenses, making them highly vulnerable to the smallest change.

Hawai‘i’s endemic plants held little nutritional value for humans, but voyagers had brought chickens, dogs and pigs to supplement their diet. They also carried stalks of kalo (taro), ‘uala (sweet potato), ‘ulu (breadfruit) and mai‘a (banana) for cultivation. In the earliest settlements located on windward O‘ahu, archeologists have unearthed remnants of lo‘i kalo, or wetland taro fields. As the population grew, communities worked together to build interlacing terraces of lo‘i kalo along with a number of fishponds to grow and harvest fish. People distributed and exchanged foods and goods across a division of land, the ahupua‘a, that ranged from the mountain to the sea. Prior to Capt. James Cook’s arrival in 1778, a large population, recently estimated at nearly 700,000, 3 thrived on the islands.

Amid such bounty, culture and language blossomed. Hawaiians created exquisite examples of weaving, kapa and feather work. They passed down mo‘olelo (stories) and oli (chant), unfolding a rich oral tradition. The Kumulipo stands as the epitome of the oli art form. This 2,100-line chant traces the evolution of life on Earth that forms the lineage of the sacred chief Lonoikamakahiki.4 King David Kalākaua received a written manuscript of the Kumulipo, which his sister, Queen Lili‘uokalani, translated to English in 1895, during her imprisonment at ‘Iolani Palace.

Hanau ke Ko‘e-enuhe ‘eli ho‘opu‘u honua

Hana kana, he Ko‘e puka

Hanau ka Pe‘a, ka Pe‘ape‘a kana keiki, puka …”

Born was the coral polyp, born was the coral, came forth

Born was the sea cucumber, his child the small sea cucumber came forth

Born was the smooth sea urchin, his child the long-spiked came forth

Born was the ring-shaped sea urchin, his child the thin-spiked came forth

— Kumulipo, lines 15–19 from the text in King David Kalākaua’s possession

2Jacobi, James D. and Atkinson, Carter T., Hawaii’s Endemic Birds, National Biological Service, Washington, D.C., 1995.

3Pew Research Center, “After 200 Years, Native Hawaiians Make a Comeback,” April 6, 2015

4In 1779, a version of the Kumulipo was recited for Captain Cook by two kahuna in a ceremony at Hiki‘au heiau in Kealakekua Bay, Hawai‘i.