Kamehameha I died in May 1819, in Kamakahonu, Hawai‘i. Early on, the king had named his son, Liholiho, successor. But two powerful women – Ka‘ahumanu and Keōpūolani, both his widow – would demand new freedoms, igniting a struggle that toppled the ancient religion.

Hawai‘i’s religion had been in decline for decades. As more foreign ships arrived in the islands, Hawaiians observed how captains and crew members disregarded the kapu with impunity. Men and women ate together on board and survived; on land, such an act was punishable by death. Foreigners also possessed items that Hawaiians coveted: ships, weapons and exotic goods. Moreover, the ali‘i and kāhuna were powerless to stop the deadly epidemics decimating the population, calling into question their overall sacred authority. Hawaiian traditions were being undone by the “gifts” of civilization.

Societal confusion was exacerbated by a tradition that called for the temporary suspension of kapu during the period of mourning after a high chief’s death. People engaged in prohibited behavior without penalty. It was the duty of the next king to bring about order by reinstating the kapu, redistributing lands and reasserting worship of the old gods. But Kamehameha’s death led to the dissolution of that very system, through the actions of these ali‘i.

Keōpūolani

Keōpūolani was a Maui ali‘i of the highest rank, born with the kapu moe, or prostrating taboo. Her sacred status ensured that her two sons by Kamehameha – Liholiho (Kamehameha II) and Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) – would continue his dynasty. Known for her gentle disposition, Keōpūolani also showed bold daring when it came to personal and political loyalties.

Queen Kaahumanu, Louis Choris. Photo of drawing from Hawaiian Mission Houses Historic Site and Archives.

Ka‘ahumanu

Kamehameha’s favorite wife and the guardian of Liholiho. While Keōpūolani outranked Ka‘ahumanu, she could not match the latter’s political acumen, spirited intelligence and commanding presence. Ka‘ahumanu often accompanied Kamehameha onto visiting vessels, where she witnessed the foreigners’ disregard for the kapu. As the only female member on Kamehameha’s council of chiefs, she was said to be the “pillar and cornerstone” of his government.2 Ka‘ahumanu also possessed the power of pu‘uhonua and could grant sanctuary to those condemned to death or exile.

Liholiho

Liholiho, eldest son of Kamehameha I and Keōpūolani. Unlike his father, Liholiho had never known a Hawai‘i without foreigners. He understood his royal duties, but often chose to spend his time carousing and playing games. At the time of Kamehameha’s death, Liholiho was around 21 years old.

In the summer of 1819, ali‘i assembled at Kamakahonu on Hawai‘i Island to install Liholiho as Kamehameha’s heir. It was a dazzling sight. The ali‘i, “radiant in feather cloaks and helmets, with Ka‘ahumanu in the center, faced the people.”3 Liholiho entered wearing a red British coat trimmed with gold lace and a feather helmet, an ‘ahu‘ula draped over his shoulders. Ka‘ahumanu greeted him holding the spear of Kamehameha I: “O heavenly one! I speak to you the commands of your grandfather [Kamehameha]. Here are the chiefs, here are the people of your ancestors, here are your guns, here are your lands. But we two shall share the rule over the land.”4 Liholiho agreed, perhaps reluctantly, bestowing on Ka‘ahumanu the title, kuhina nui, or chief counselor. It was the first time a woman had achieved such a powerful political role in Hawai‘i.

But Ka‘ahumanu had more on her mind. She went on to explain that while some may wish to obey the reinstated kapu, she and her people wanted to be free from it. “We intend that the husband’s food and the wife’s food shall be cooked in the same oven and that they shall be permitted to eat out of the same calabash. We intend to eat pork and bananas and coconuts. … we are resolved to be free.”5

The king kept silent and hastened to Kawaiahae to ponder the decision. He understood that “a Mō‘ī (king) who did not uphold the ‘Aikapu had not long to rule,”6 but he also recognized that other ali‘i would certainly challenge him if Ka‘ahumanu withheld support. Seeing Liholiho’s indecision, Keōpūolani called for her five-year-old son and the two sat down and ate together. Keōpūolani’s sacred rank consecrated the act of ‘ai noa, or free eating.

The New Reign

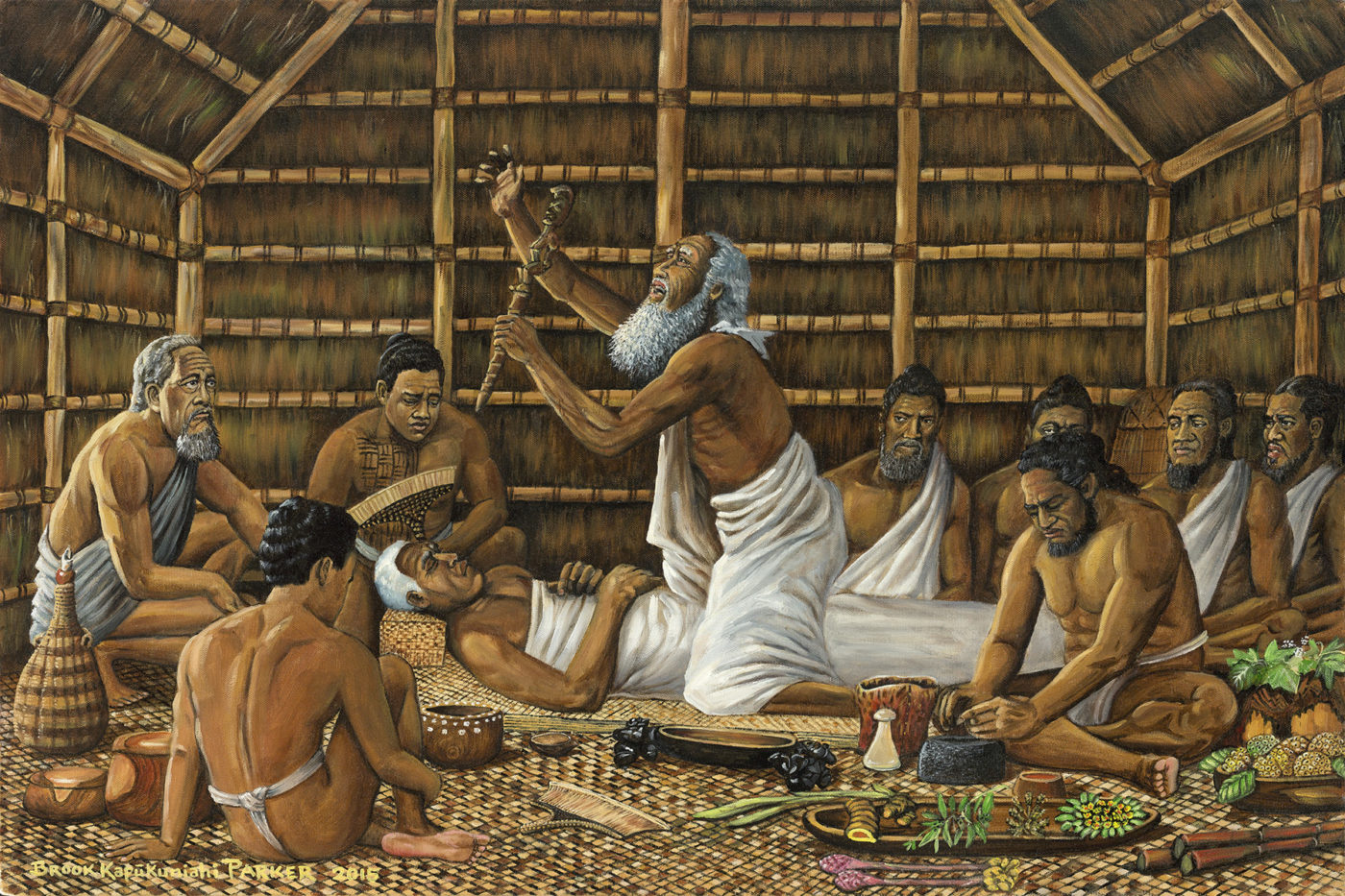

In November 1819, six months after becoming king, Liholiho made his decision. He had consulted the high priest Hewahewa, who gave his approval. He also cemented the loyalty of his ali‘i, by restoring their rights to the sandalwood trade, monopolized under Kamehameha.

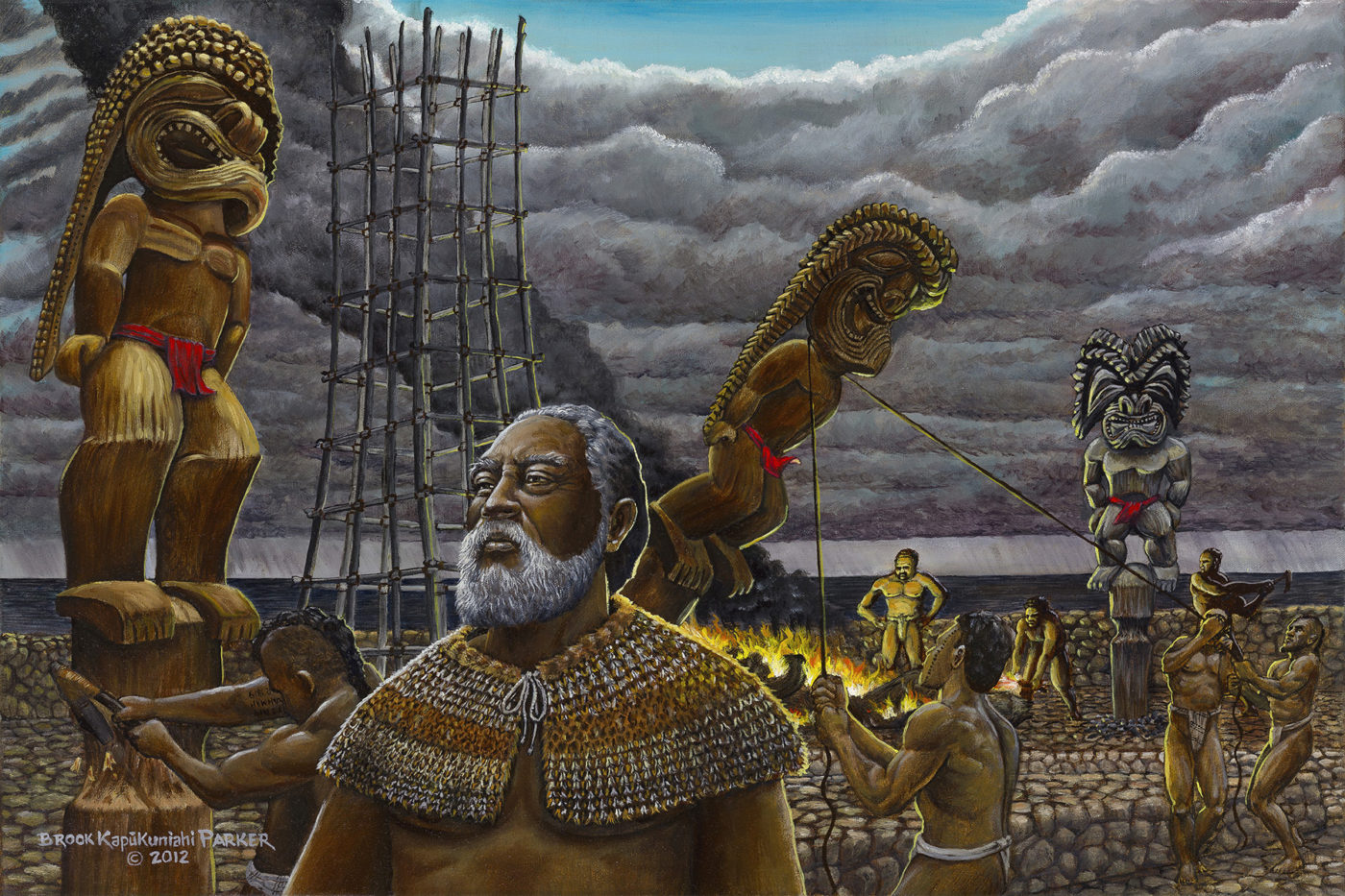

Near Ahu‘ena heiau in Kailua, Hawai‘i Island, a grand feast was underway when Liholiho stepped onto shore. Two tables were set up, one for the men and the other for the women. Liholiho circled the tables with seeming indecision, then sat down abruptly with the women and began to eat. Surprised onlookers exclaimed, “‘Ai noa, ‘ai noa!” Following the feast, Liholiho pronounced the end of the kapu and ordered the destruction of all heiau. Messengers fanned out across the islands, spreading the news as far as Kaua‘i. High priest Hewahewa led the way by setting fire to a hundred wooden idols at a heiau nearby.

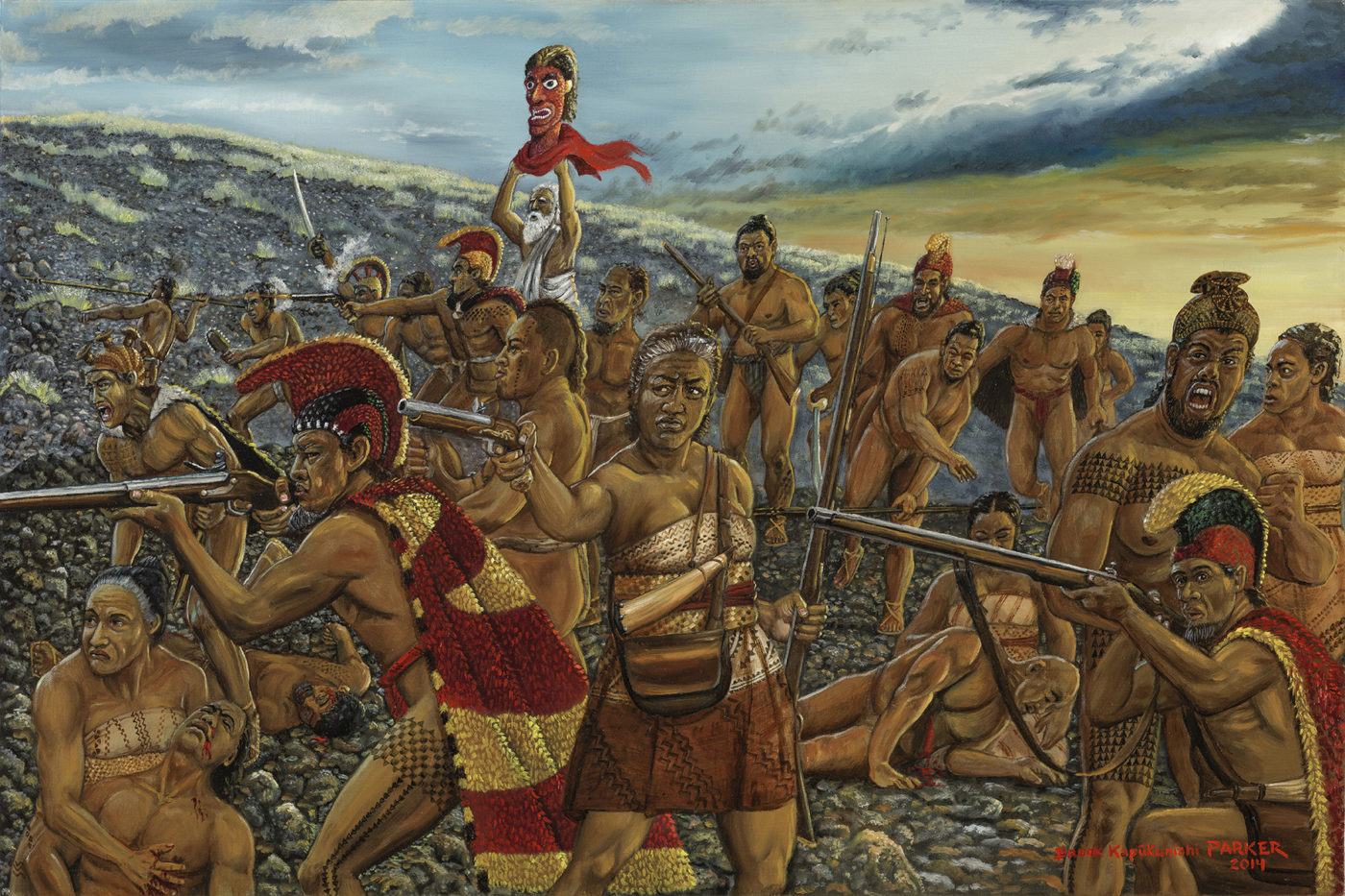

Not all ali‘i agreed with the King’s edicts. Liholiho’s cousin, Kekuaokalani, who had inherited the war god, Kūkā‘ilimoku, from Kamehameha, struggled to uphold the ancient religion. He mounted a last-ditch uprising at Kuamo‘o, but was killed by the king’s more powerful forces. Ka‘ahumanu herself directed the marine forces that decisively quelled the rebellion.

Liholiho, with Ka‘ahumanu and Keōpūolani, succeeded in overthrowing the religion that had governed Hawai‘i for a thousand years. But little thought was given to what would follow. Until the following spring, when a ship from Boston, carrying 14 missionaries, sailed into Kailua, Kona.

— Kapihe’s prophecy on the dismantling of the kapu, imparted to Kamehameha I.7

“When Liholiho began to break the kapus and men and women began to eat together, I had a real abhorrence of his conduct, and even wept aloud in his presence, saying to him: ‘We must forsake this work at once, or god will be angry at us.’”

— John Papa Ī‘ī, attendant to Liholiho

2Ibid. pp. 313–314, 318.

3Mo‘okini, Esther. “Keopuolani, Sacred Wife, Queen Mother, 1778–1823,” The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 32, 1998, p. 15.

4Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii, p. 220.

5Alexander, W.D., “Overthrow of the Ancient Tabu System in the Hawaiian Islands,” Originally published in The Hawaiian Monthly, April 1884; reprinted in the 25th Annual Report of the Hawaiian Historical Society for the Year 1916, Paradise of the Pacific Press, Honolulu, 1917, p. 37.

6Kame‘eleihiwa, Lilikalā, Native Land and Foreign Desires, Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu, 1992, p. 75.

7Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii, p. 223.

8Kame‘eleihiwa, Native Land and Foreign Desires, p. 78.