Jason Kimata ’84 is currently an associate professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. He also is the co-director of the school’s doctoral program in immunology and microbiology. (The views he expresses below are his own.)

By Jason Kimata ’84

I don’t normally study coronaviruses, but my training and expertise are in molecular biology and virology. The research I’ve been doing for the past 20 years has mainly been on how HIV is able to evade and suppress the host immune response to persistently infect a person.

Since the pandemic, my laboratory has been working collaboratively with several other groups on studies of neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2-infected people.

We are characterizing antibodies in convalescent sera patients (those who have recovered from COVID-19) that will be used as a therapeutic for seriously ill patients with active COVID-19 disease. This treatment – convalescent plasma therapy or adoptive immunotherapy – is an old concept that works for curing or preventing infections by other viruses. In fact, there is a nationwide trial to examine how well it works for COVID-19.

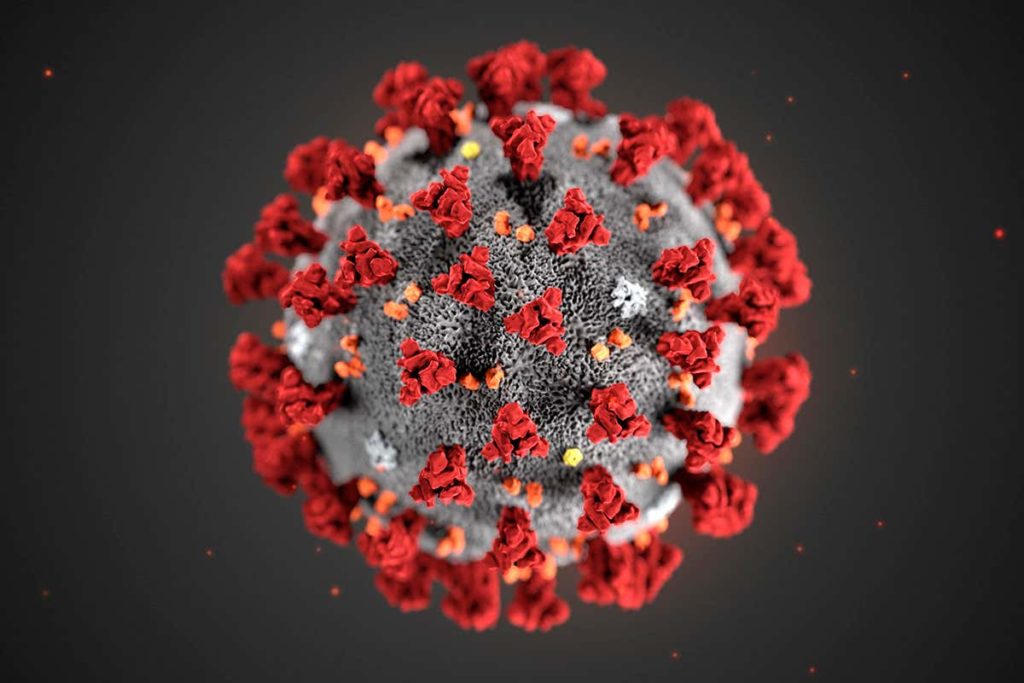

As we expect, not every donor sera will have a positive effect, it presents an opportunity to understand the types and quantities of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies necessary to cure infection. We want to know the types of antibodies produced against the spike, where they bind the protein, and of course, if they neutralize the virus. If we can define which antibodies are most effective for inhibiting replication of the virus, we can improve selection of convalescent plasma that are likely to work therapeutically. Furthermore, we can identify the anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody producing cells from the donors, clone those antibodies, and then mass produce them for use as a therapeutic product. As we do this, we will learn a lot about anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody producing cells and why some people with COVID19 have strong antibody responses to infection while others do not. Knowing this, will help us define the characteristics of a good vaccine.

As you have heard in the news, what makes the current situation so challenging is the lack of antiviral tools for preventing or treating disease. Neither vaccines nor new drugs can be rapidly developed and tested for safety and efficacy. We know transfusing antibodies is generally safe and may lead to improvements in disease.

In the case of neutralizing antibodies, nature has already done the hard work of selectively producing highly specific antiviral molecules (i.e. antibodies) targeting the virus.

In academia, I have the freedom to choose the direction of my research. Having said that, I didn’t have a choice about what I could work on since early March, because our regular research projects were shut down when our campus was closed to everyone except essential personnel needed for clinical care, COVID19 research or critical resources. Nevertheless, I selected an area of research on COVID19 where my laboratory has skills and could interphase with a clinical effort of high importance and provide our expertise. For me and many of my colleagues, it is a matter of serious concern that we don’t have any effective antiviral strategies except social distancing and masks. I do believe we have a moral obligation to support the clinical mission and change that as quickly as possible.