Hawaiians quickly took to reading and writing but were slower to accept Christianity. Ali‘i such as Keōpūolani and Ka‘ahumanu, however, fervently embraced this faith, which enabled the missionaries’ increased influence. Efforts to build churches (funded by the ali‘i), to print hymnals in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i and to translate the Bible drew the populace to the work of the mission.

Embracing Christianity

- In 1823, Keōpūolani became the first ali‘i to convert to Christianity after the arrival of the missionaries. Ka‘ahumanu decided also to convert, convinced that the Binghams’ prayers had restored her health in 1821 and that Jehovah had helped her army crush a rebellion on Kaua‘i in 1824.

- Ka‘ahumanu may have been drawn to Christianity’s promise of eternal life, or ke ola hou. As Hawaiians continued to perish from foreign diseases, ke ola hou offered the queen an especially tempting promise.1

- After Ka‘ahumanu’s conversion in 1825, she, accompanied by the Binghams, circled the islands to encourage Hawaiians to embrace Jehovah.

- By 1840, the Protestant church recorded 20,000 conversions, and Hawai‘i officially became a Christian nation.2

— Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa, Native Lands and Foreign Desires, p. 139

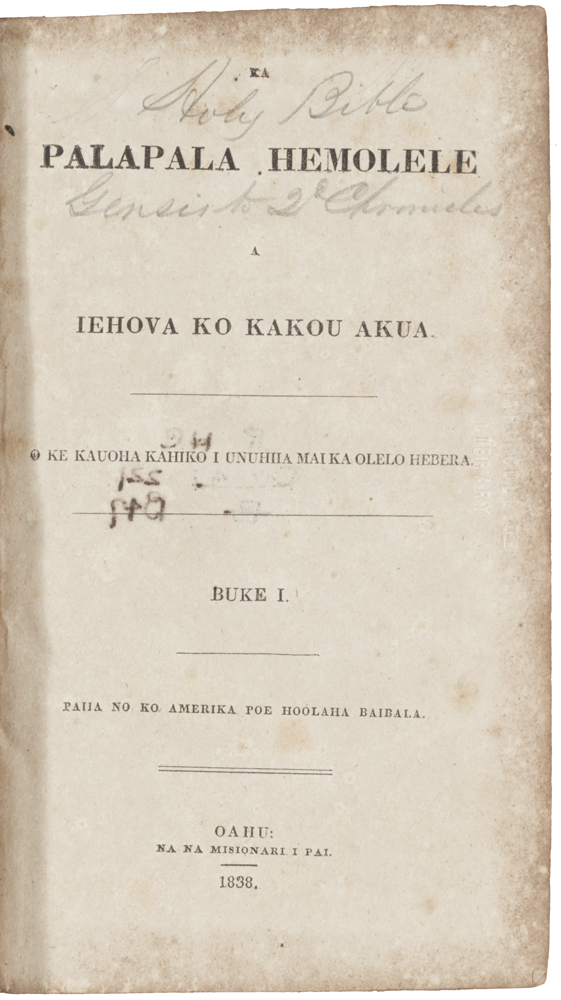

Baibala

— Jeffery Lyon, “No ka Baibala Hemolele: The Making of the Hawaiian Bible,” p.118

- Hiram Bingham led the monumental task of translating the Bible into Hawaiian. After individual efforts at translation, in 1826 Bingham and William Richards gathered a team of at least four other missionaries and five Hawaiian ali‘i and chiefly advisors.

- With the seminary-educated missionaries knowledge of the biblical text in Hebrew, Aramaic and ancient Greek, and the Hawaiians’ scholarship in the language and oral literature of Hawai‘i, together they painstakingly worked and reworked each verse of the Bible, aiming for the language to be “clear, stately, and reflect the language as spoken by the ali‘i.”3

- At the beginning, only one or two verses were completed in a day. In 1832, the New Testament was printed. By 1839, the complete edition of the Bible in Hawaiian was released.

— Jeffery Lyon, “No ka Baibala Hemolele: The Making of the Hawaiian Bible,” p.140

Churches

- The first churches were thatched hale, but growing congregations evidenced the need for larger, more permanent structures. The first stone church, Mokuaikaua, was completed in Kailua-Kona in 1837.

- 1n 1838, construction in Honolulu began to replace the thatched Kawaiaha‘o Church with stone. Designed by Hiram Bingham, Kawaiaha‘o was constructed from 14,000 hand-hewn coral slabs, each weighing more than 1,000 pounds. Kawaiaha‘o Church was dedicated on July 21, 1842.

— American merchant Stephen Reynolds from his journal

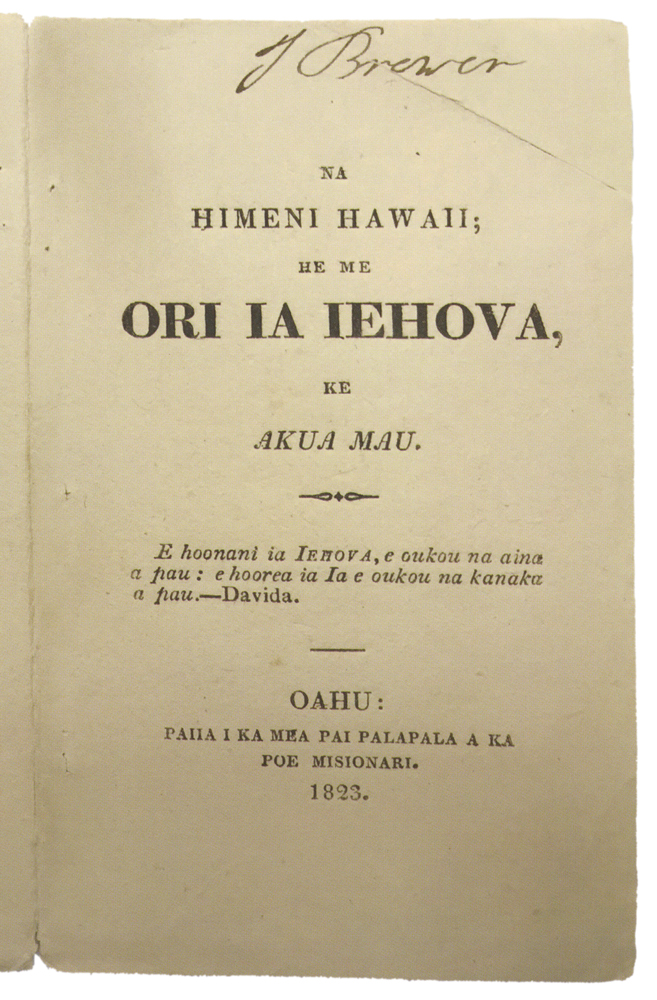

Hymnals and Hymns

- Hymns were an enticement for the Hawaiians to attend church services, and the early, prolific printing of Hawaiian language hymnals followed the example learned from Rev. Ellis and the Tahitians.

- Missionaries contributed to an enduring body of Hawaiian hymns. These include “Ho‘onani I Ka Makua Mau,” by the Rev. Hiram Bingham (first verse), and the beloved anthem, “Hawai‘i Aloha,” by the Rev. Lorenzo Lyons.

Christianity brought to Hawai‘i a belief system that aided education, literacy and social cohesion. It also established a set of moral and secular values that fundamentally clashed with those of Hawaiian culture. Bans on hula dancing or playing games, the need for sustained labor and piety were difficult for Hawaiians to understand, much less live up to. But the main gap in understanding between Westerners and Hawaiians lay in how they each viewed the land. This difference would become a lightning rod for conflict in the coming decades.

1 Dr. Kame‘eleihiwa, Lilikalā K., Native Land and Foreign Desires, Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu, 1992, p. 142.

2 Kuykendall, Ralph S., The Hawaiian Kingdom, Vol. 1, 1778-1854, The University Press of Hawai‘i, Honolulu, 1978, first printed in 1938, p. 115.

3 Lyon, Jeffrey, “No ka Baibala Hemolele: The Making of the Hawaiian Bible,” Palapala Volume I (2017), The University Press of Hawai‘i, Honolulu, 2017, p.118.