From the first arrival of foreigners in Hawai‘i in 1778, Hawaiians perished from introduced diseases at an alarming rate. By 1840, the Hawaiian population had declined 84 percent to around 109,000. This devastating population loss was compounded by the rising number of Hawaiians leaving ali‘i lands for life in the towns and at sea, and leading to early imports of foreign workers to boost the economy. The impact was systemic – economic, social and cultural – seeding doubt in healing methods and the gods that traditionally protected them.

Dramatic Population Loss

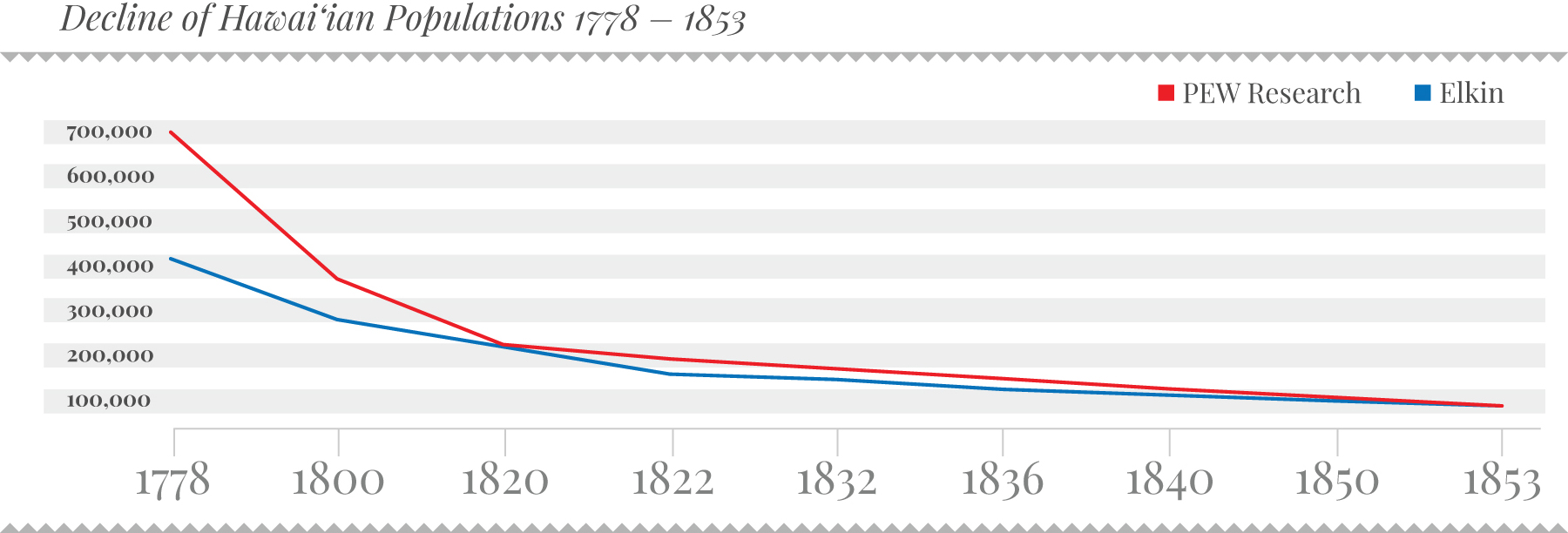

- The first census taken in Hawai‘i was in 1831 – 1832 by the missionaries, officially recording a population of 129,814 Hawaiians. While estimates of pre-contact population range widely, research suggests a population between 400,000 – 700,000, signs of massive decline are clear.

- Rapid decline continued. From 1832 – 1836, approximately 22,000 died of whooping cough and measles. In 1839, an epidemic of mumps hit the islands.

- During 1848 – 1849, “Measles, whooping cough, dysentery, and influenza raged across the kingdom. An estimated 10,000 persons died from these causes, more than one-tenth of the population.”11 The death toll was one of the worst in Hawaiian history.

— Pew Research Center, 2015 (Note: this is based on the estimate of about 700,000 pre-contact)

Causes of the Decline

- Trade with California and Mexico introduced new diseases. “The measles was brought from Mazatlan, Mexico, by an American naval frigate … whooping cough arrived on a ship from California about the same time.”13

- Trade also lured adventurous young men from their homes, adding to population decline. “From 1845 – 1847, approximately 2,000 Hawaiians signed up to serve on foreign ships.”14 Many of them never returned to live in the islands.

Impact of Population Loss

- Hawaiians experienced tremendous suffering during the epidemics. The trauma caused many Hawaiians to re-evaluate traditional systems that no longer served to protect them.

— Dwight Baldwin, a missionary doctor in Lahaina, writing on December 15, 1848

- Heavy personal and cultural losses were accompanied by a bitter economic toll. Increasing numbers of maka‘āinana moved to Honolulu, Hilo and Lahaina for jobs or elected to work on foreigner-run plantations. This left ali‘i lands uncultivated and unproductive. Consequently, the ali‘i became more open to new commercial ventures that hinged on global, rather than local, markets.

— Sumner LaCroix, Hawai‘i: Eight Hundred Years of Political and Economic Change, p.103

Plantations, hailed as Hawai‘i’s new economic engine, stalled from the lack of workers. The Hawaiian government began importing contract laborers from foreign nations, including China. A significant number of workers decided to remain in the islands after their contracts ended. Hawai‘i’s demographic mix was changing. Hawaiians were headed to becoming a minority in their own homeland.

11 Schmitt, Robert C. and Nordyke, Eleanor C. “Death in Hawai’i: The Epidemics of 1848-1849,” The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 35, 2001, p. 1.

12 Goo, Sara Kehaulani, “After 200 Years, Native Hawaiians Making a Comeback”, Pew Research Center, April 6, 2015. Elkin, W. B., “An Inquiry into the Causes of the Decrease of the Hawaiian People,” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 6, No. 3, November, 1902, pp. 398-411.

13 Schmitt and Nordyke, Ibid.

14 Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, p. 312.