On Solid Ground

By Carlyn Tani ’69

JOHN HARA ’51

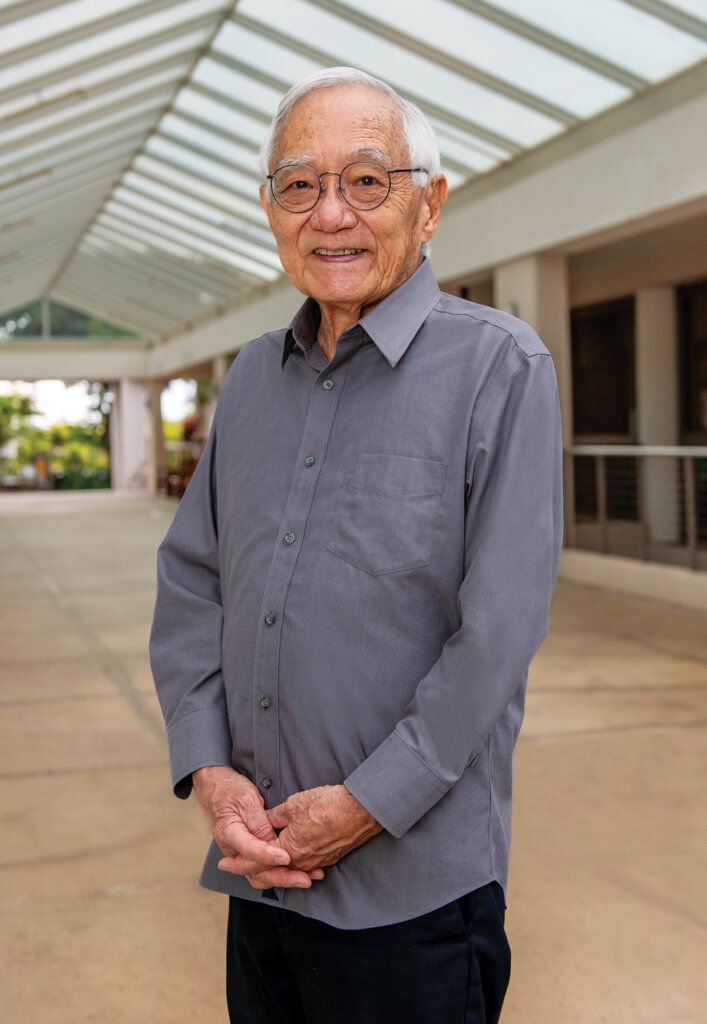

On a brisk spring morning, John Hara ’57 leads me through Mamiya Science Center. It’s been a while since the renowned architect has set foot in the building he designed 30 years ago, and the visit stirs memories of his own student days catching crayfish in the Lily Pond, taking oboe lessons in Montague and hanging out in high school with friends at the Ka Punahou office. Academy students nearby are clustering around a set of concrete tables. “We designed these areas so they would have a place to get together,” Hara explains. He pauses amid a spacious interior corridor and points out, “From here you can see Old School Hall on one side and Pauahi Hall on the other.” In designing the building, Hara aligned the corridor sightlines with campus landmarks to connect students to their history; in thinking about the space, he allowed for ample meeting areas to connect them with one other. For Hara, architecture is not about a particular style but about creating environments that illuminate the human experience.

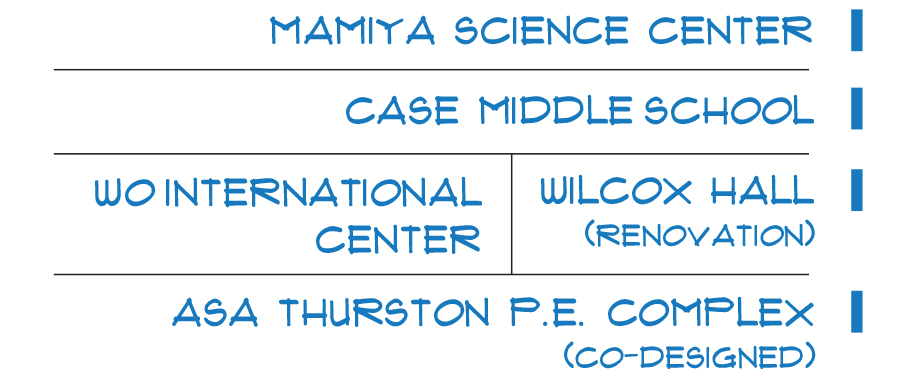

John Hara and his father, Ernest (1928), are among the illustrious architects who’ve made the Punahou campus an exemplar of educational building design. The list includes luminaries such as Charles W. Dickey, Bertram Goodhue and Vladimir Ossipoff. John Hara designed an unprecedented 25 projects for the School, ranging from the renovations of Wilcox Hall and Old School Hall to the construction of Case Middle School. “John has shaped the Punahou campus more than any other architect,” says Glenn Mason of MASON, a firm specializing in historic preservation. “He’s an exceptional talent. He’s one of the best architects who’s ever practiced in Hawai‘i.”

Over a four-decade career, Hara has designed some of Hawai‘i’s most celebrated spaces, including the Maui Arts & Cultural Center, the Clare Boothe Luce Wing and the Luce Pavilion of the Honolulu Museum of Art. His portfolio of private homes, commercial buildings, schools and public institutions has earned him countless awards, including the Medal of Honor for Lifetime Achievement from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Northwest and Pacific Region.

Beyond the glitter of the accolades, Hara has forged a profound legacy. An early proponent of “green” design, Hara helped spur the movement for greater energy efficiency in buildings. Alongside his impressive architectural imprint on campus, Hara helped spearhead a pivotal building process, known as design assist, which has supercharged teaching and learning experiences at Punahou – and is a compass for construction projects to this day.

Constructive Dialogue

Punahou, like other schools, had historically left building design in the hands of the architects. But that all changed in the 1990s, as then-President Jim Scott ’70 and school leaders faced the pressing challenge of replacing MacNeil Hall. When it opened in 1955 as a hub for teaching science in the Academy, the facility was cutting edge. However, as the decades passed, the aging structure struggled to meet the growing needs of the School. Simple essentials, like having enough electrical outlets or well-ventilated classrooms posed significant challenges. The necessity for a new facility became apparent – and the vision for what would become the Mamiya Science Center began to take form.

“John’s design of having distinct yet connected spaces for learning really facilitated a team-based approach, ensuring that each student is known. This aligns with our instructional vision, which prioritizes the development of the whole child.” – Junior School Principal, Todd Chow-Hoy

The bold new project integrated design assist, bringing together architects, engineers and contractors at the onset of the design process, paving the path for greater coordination and swift pivoting, if necessary. But the real game-changer? The inclusion of educators. Their insights would ensure the design was not only functional, but also tailored to the needs of the primary end-users. School leadership, Physical Plant, and Development were also at the planning table to provide diverse perspectives. Mamiya’s steering committee was up and running.

“It was part of an ecosystem of thought where people were beginning to understand how physical spaces craft the way we think and learn,” explains Ruth Fletcher, then-science department co-chair and current President and Head of School of St. Andrews Schools. “So we wanted to design something that was good for kids and for science education over the next 50 years.”

Punahou was among the first schools in Hawai‘i to harness design assist – a method so successful that multi-stakeholder engagement is now a hallmark of every construction project at the School. The rewards of using design assist are substantial, though there is a significant amount of heavy lifting in the beginning, as Hara can attest.

He sat in on weekly meetings as Academy faculty conducted extensive surveys and research on leading models of science instruction. “He was an amazing listener,” recalls Fletcher. “He made sure he really understood us, so he garnered the trust of teachers. And when we’d finally decided on a space, he’d ask us, ‘What do you want next to that?’” During the process, Hara was intently focused on the role of sunlight. “He was always imagining the use of light and of having nature come in the windows,” she says. Faculty ultimately coalesced around the mission of “making science visible.”

Walk through the Mamiya Science Center today and its expansive classroom windows might reveal students launching small projectiles into the air for a Physics lab or examining a human skull in Anatomy and Physiology. For faculty, teaching in the new building was “spectacular,” says Fletcher. “We could do things we just couldn’t do before. For instance, Chemistry classrooms have a lecture area and a lab so students can move between the two areas without disruption, which was great.” Hara incorporated energy-efficient air conditioning and other sustainable elements into the building but its most innovative feature was 5,000 square feet of open, unprogrammed space, which can be reconfigured to evolving needs. Today, the D. Kenneth Richardson ’48 Learning Lab serves as a vital catalyst for design innovation.

“The idea of architecture is that it allows changes to happen. Education is constantly evolving and if the buildings can accommodate that, that’s the test.” – John Hara ’57

Mamiya, which opened in 1999, sits amidst an eclectic suite of historic buildings – Old School Hall, Pauahi Hall, Montague and Dillingham Hall. The Center’s clean lines and graceful proportions are contemporary interpretations of C.W. Dickey’s iconic Territorial-era style (turn to page 27), exemplified by neighboring Montague. Mamiya’s sloping, green-tiled roof and cream-colored, textured walls echo the rooflines and stucco exteriors of Montague and Dillingham Halls, while the unadorned nature of its structure evokes that of Old School Hall, built in 1851. These architectural elements establish a visual connection between the disparate structures. “It’s important to understand the history of a place, to understand the history of Punahou,” Hara explains.

Hara defined the architect’s role as a mentor who works closely with teachers, school leadership and staff. “The important thing was listening to the people who are going to use the buildings. As architects, we always have ideas but these would evolve just by talking with the teachers,” he explains. “It was a very collaborative effort.”

When Hara was in sixth grade at Punahou, he discovered a deep love of music. He took up the oboe and performed with the Honolulu Symphony while in high school. He entered the University of Pennsylvania intending to major in music, but classes with architectural greats Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi and Romaldo Giurgola inspired him to study architecture instead. Hara nonetheless brings a musician’s sensibility to his work, which has a distinctive sense of form, rhythm and harmony. Hara launched his career in France and Switzerland before returning to Hawai‘i, where he married his late wife, Marie Murphy ’61 Hara, a writer and assistant professor of English at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Since opening his own firm in 1970, he’s been a vigorous advocate for Hawai‘i architecture reflective of the islands’ history and environment.

Interconnected by Design

In 1999, Punahou received a major gift from America Online co-founder Steve Case ’76 to build a new middle school. The traditional design of Bishop Hall, which housed the 7th and 8th-grades, kept teachers isolated from one another in self-contained classrooms that sometimes overflowed with students. Faculty on the Steering Committee, led by then-Junior School principal Mike Walker, immersed themselves in educational best practices and embraced ground-breaking research from neuroscience on how adolescents learn. Case represents a transformation of a child’s middle school experience at Punahou. The School’s grade-level configuration, team structure, curriculum and buildings are designed to foster adolescent learning, growth and belonging. It combines sixth grade with seventh- and eighth-grades, organizing each grade into smaller teams. Teachers from math, science, social studies and English occupy adjacent classrooms and collaborate on an interdisciplinary curriculum.

“As teachers, being that close to one another allowed us to have a lot of casual conversations about curriculum and about students,” says Todd Chow-Hoy, Junior School Principal, who taught math at the time. “The curriculum came to life because our team spent a lot of time talking about the interconnectedness of what students needed to learn.” Teachers’ proximity also gave them flexibility with scheduling so they could allot more time for students to complete a project. “John’s design of having distinct yet connected spaces for learning really facilitated a team-based approach, ensuring that each student is known. This aligns with our instructional vision, which prioritizes the development of the whole child,” explains Chow-Hoy.

Throughout the building process, Hara paid attention to all the details, says Charlotte Kamikawa, project engineer for the campus construction team.

Punahou faculty and other stakeholders during a brainstorming session.

“He made sure the colors of the lockers matched the color of the accent walls. And he came up with the idea of organizing the grade levels by color. Not many lead architects would be that hands-on.” Case initially opened in 2004, and the next year received an Award of Excellence from the AIA, Honolulu Chapter.

Several of Mamiya’s experimental elements blossomed into major features at the Middle School. Mamiya’s unprogrammed spaces paved the way for Case’s team spaces and creative learning centers; its flexible spatial design led to moveable walls between classrooms; and the School’s interest in sustainability prompted the pursuit of LEED certification from the U.S. Green Building Council. In 2006, Case Middle School became the first building complex in Hawai‘i to receive LEED Gold designation and was named the “Greenest School in America” by the Green Guide.

Case also is layered with personal meaning for Hara. Two of his grandchildren are now flourishing in its classrooms (and a third is in 3rd grade). When asked what he’s proudest of with Case Middle School, Hara highlights the fact that teachers are still finding new ways to utilize its spaces. “The idea of architecture is that it allows changes to happen. Education is constantly evolving and if the buildings can accommodate that, that’s the test,” he says.

At the Crossroads of Innovation and History

The next chapter of educational transformation is unfolding now on the Academy campus, as Cooke Library is being renovated into the Mary Kawena Pukui Learning Commons. Designed by the late Philip “Pip” White ’66, of WhiteSpace Architects, the LEED-certified building will provide collaborative spaces for students to tackle real-world concerns using emergent technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). Kylee Mar, director of Archives and Special Collections, is excited about the Commons, which will give the School Archives a permanent home. In this new space, Mar explains, “a student will be able to draw from the history in the Archives and library collection, work in future technologies, then go down to the Design, Technology and Engineering Lab to prototype something with their own hands. They’ll be using resources from different time periods to tell the story.” Among the resources available to students is Hara’s architectural archives, an extensive collection of blueprints, drawings and hand-built models chronicling his decades-long work on campus.

“The important thing was listening to the people who are going to use the buildings. As architects, we always have ideas but these would evolve just by talking with the teachers,” he explains. “It was a very collaborative effort.” – John Hara ’57

When Hara visits Punahou nowadays, he often sits on a wooden bench in the courtyard of Sullivan Administration Building, which his father designed and he later renovated. The Punahou campus is a three-dimensional map evoking a lifetime of memories. In its contours, he sees himself as a young child playing in the Lily Pond, a teen practicing oboe in Montague Hall, a rising architect working with his father on Asa Thurston P.E. Complex, an acclaimed master designing Case Middle School alongside his two daughters, a proud grandfather.

As Hara watches the sunlight falling across the courtyard, teachers and students occasionally walk by, many of them unaware that the pensive silver-haired gentleman sitting quietly on the bench has envisioned and brought to life many of the spaces in which they now explore, wonder and discover their purpose.

Main Article: Blueprints for Learning: The Architects Who Shaped Punahou’s Campus