Captain James CookThis portrait of Captain Cook was painted by Nathaniel Dance in 1776, before Cook left London for his third voyage, which brought him to Hawai‘i. From Captain Cook’s Artists in the Pacific 1769-1779, compiled by Anthony Murray-Oliver.

Captain James Cook was a British naval officer and explorer who commanded three voyages to the Pacific. In 1768, he led a team of scientists in an official expedition to Tahiti to observe the Transit of Venus. Privately, he carried orders from the Admiralty to claim any “undiscovered” Pacific islands for Britain, with an eye to assessing the islands’ natural resources. On this voyage, Cook mapped Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the eastern coast of Australia, while the expedition’s botanists collected more than 3,000 plant specimens. In 1772, Cook sought to circumnavigate Antarctica, leading him to survey Tonga, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Norfolk Island, New Caledonia and Vanuatu.

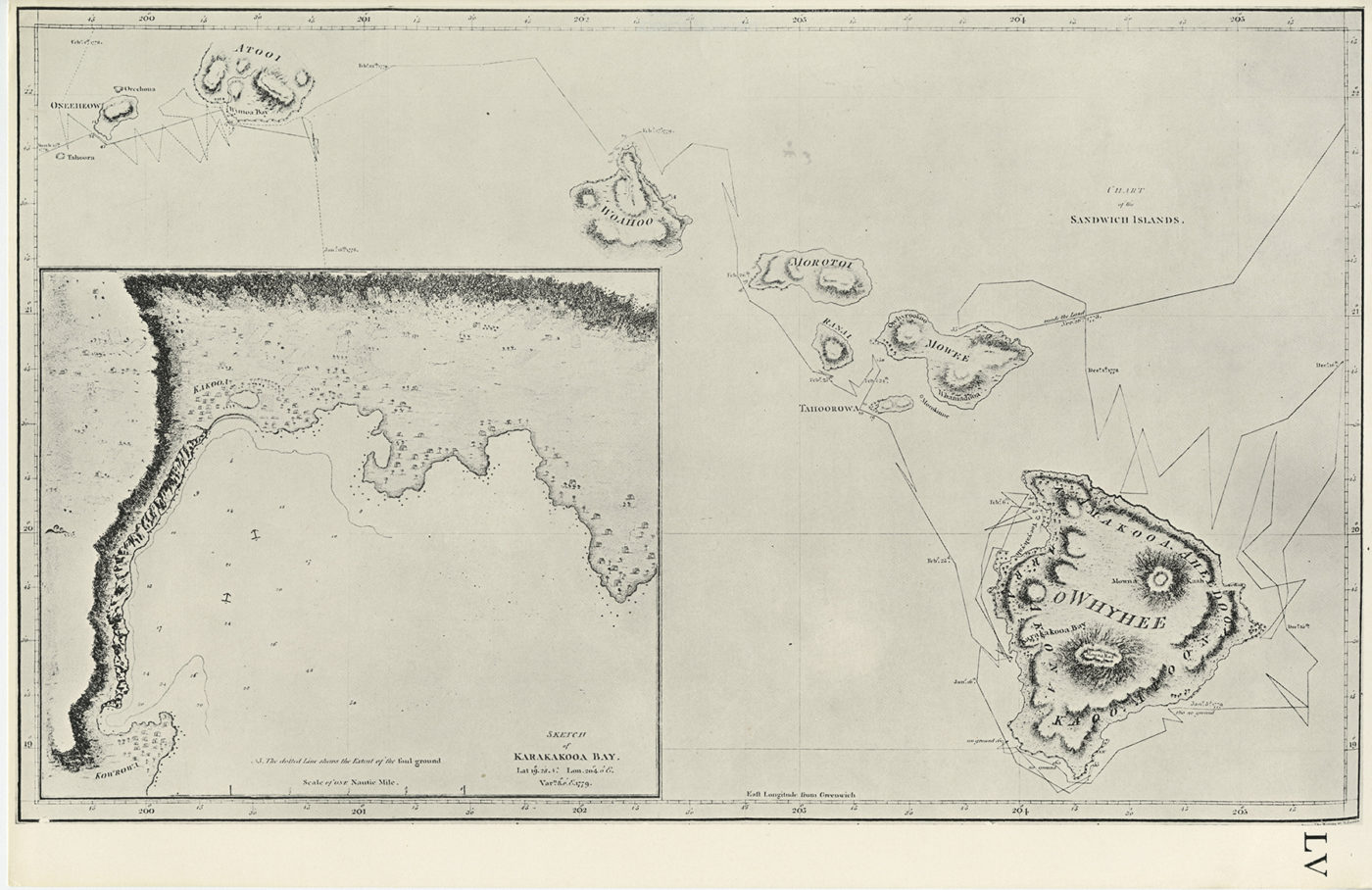

In 1776, commanding HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery, Cook set out to find a northwest passage around Alaska and Canada. On January 18, 1778, the ships sighted O‘ahu and Ni‘ihau, and set anchor at Waimea, Kaua‘i. On land, “chiefs and commoners saw the wonderful sight and marveled at it. Some were terrified and shrieked with fear.” But the kahuna Ku‘ohu interpreted the ship as the arrival of the temple of Lono, the god of fertility and agriculture. “That can be nothing else than the heiau of Lono, the tower of Ke-o-lewa, and the place of sacrifice at the altar,”1 he declared. In his journal, Cook noted that Hawaiians paddled out to the ships and “… exchanged a few fish they had in the Canoes for any thing we offered them, but valued nails, or iron above every other thing.” He named the archipelago the Sandwich Islands in honor of the Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty.

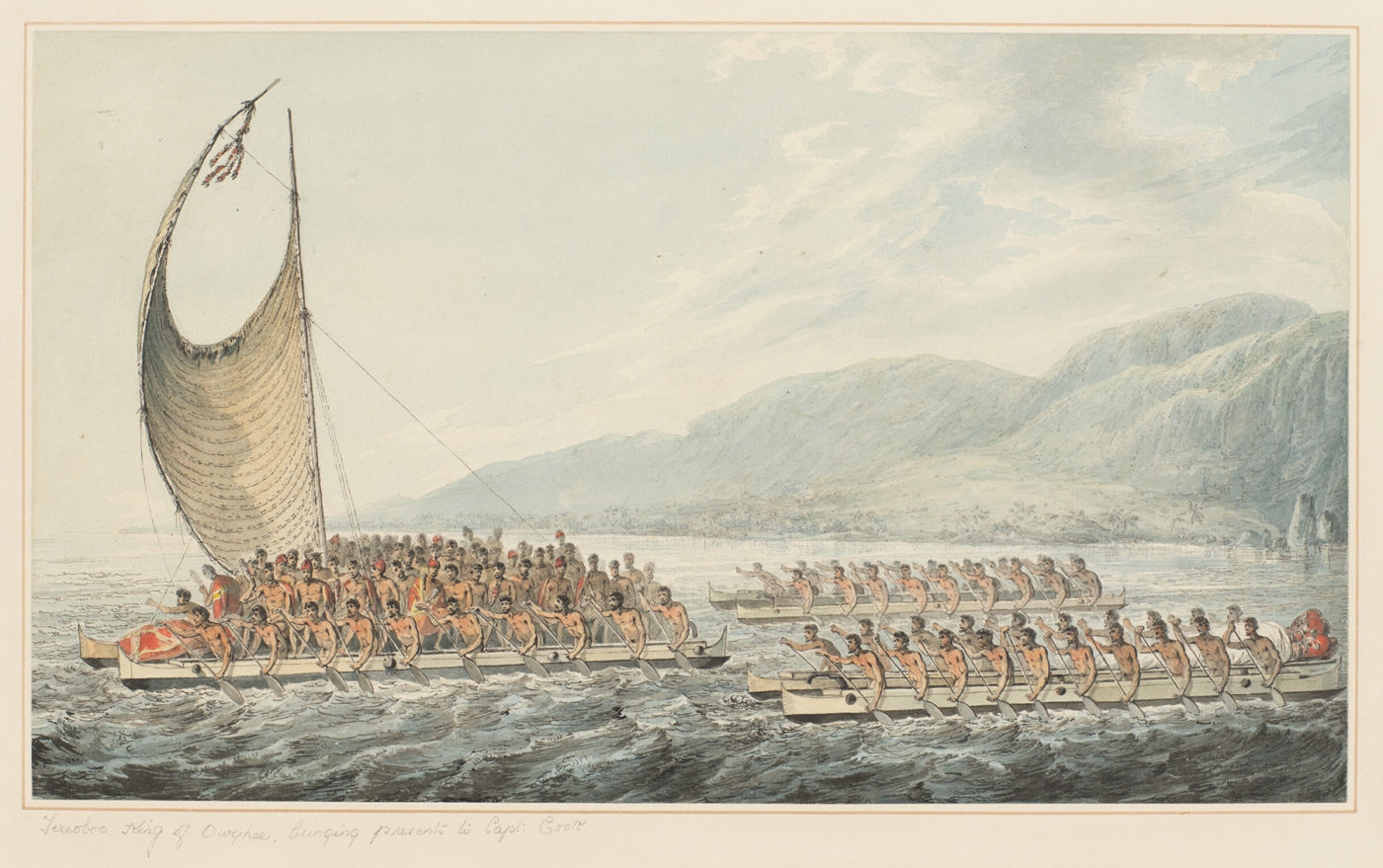

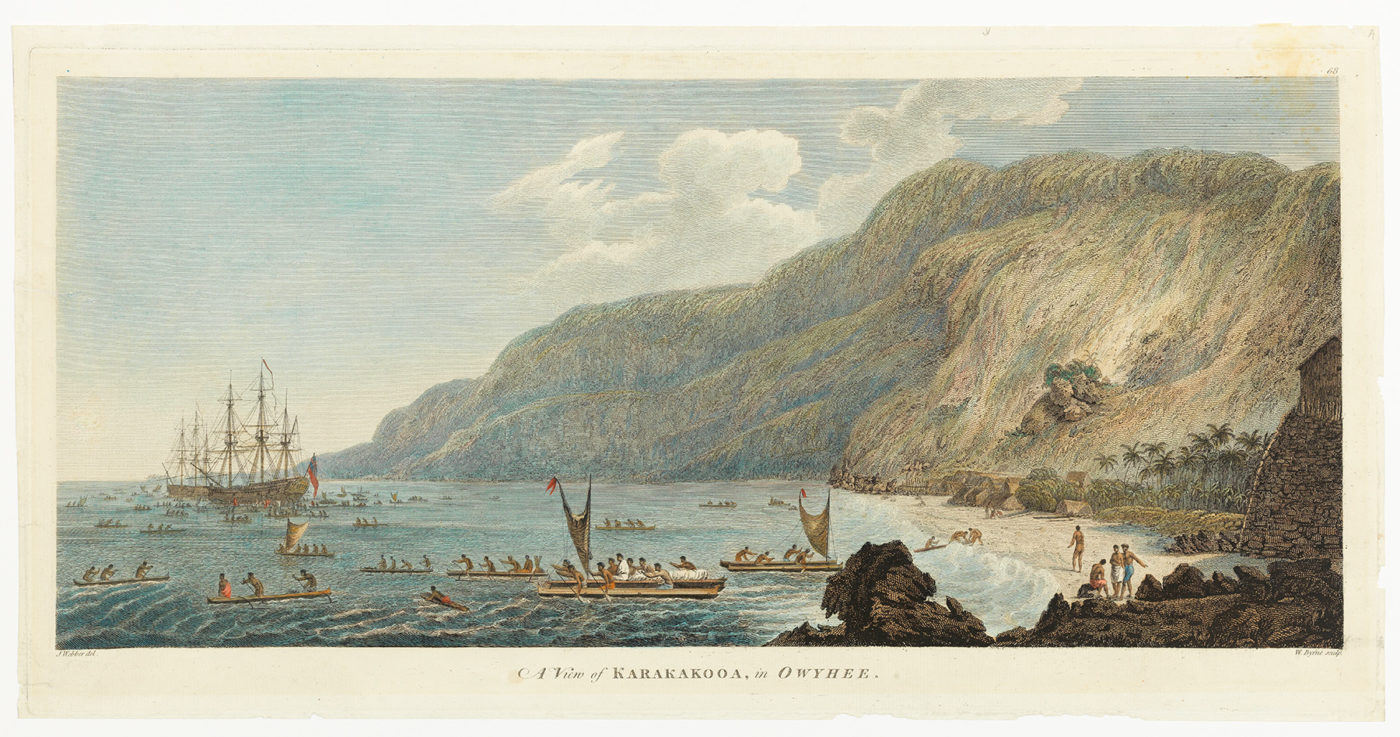

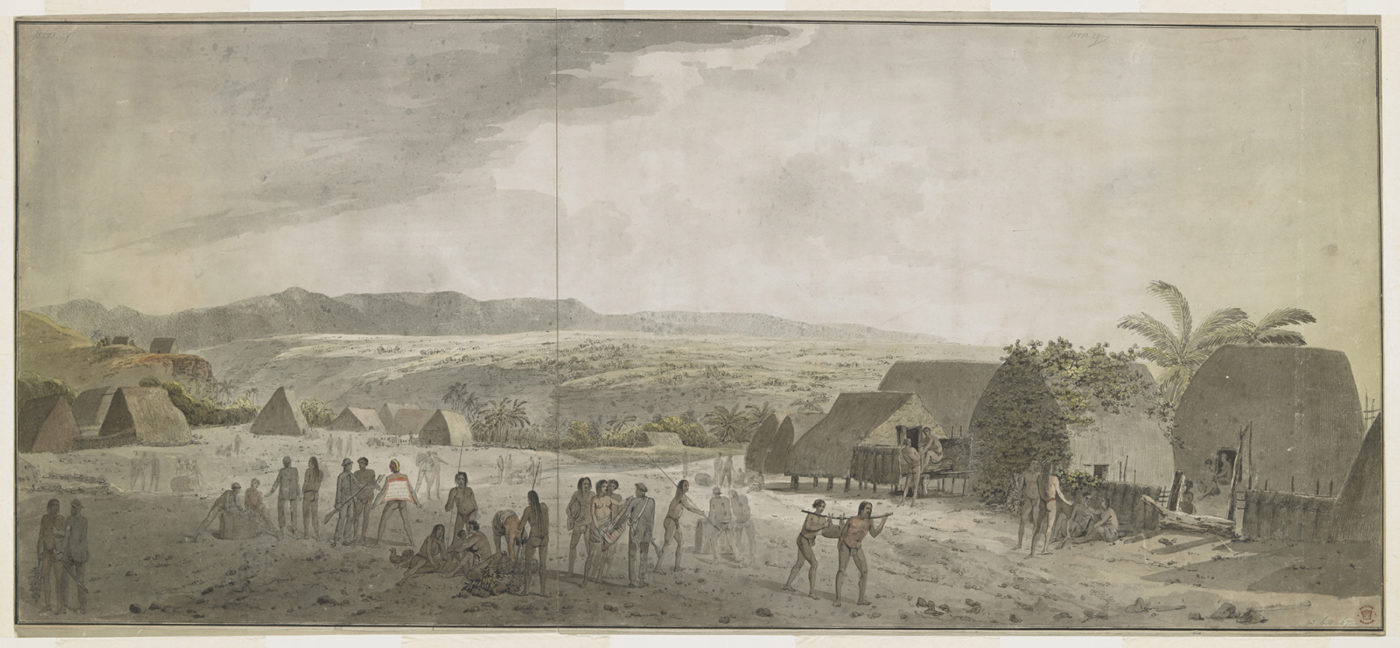

Cook departed to explore American’s northwest coast and returned to Kealakekua Bay, Hawai‘i, in November 1778. By then, word had spread across the islands about the arrival of “Lono.” The expedition was welcomed by 1,500 canoes and feted with grand hospitality. Ali‘i nui Kalani‘ōpu‘u presented Cook with “feather capes, helmets, kahili, feather leis, wooden bowls beautifully shaped, tapa cloths of every variety, finely-woven mats of Puna, and some especially fine mats made of pandanus blossoms.”2 The expedition set off months later but was forced to return to repair a broken foremast. Within one year of Cook’s initial arrival, relations had soured irrevocably. On February 14, 1779, seeking the return of a stolen boat, Cook took an armed contingent ashore to take Kalani‘ōpu‘u hostage. A violent melee broke out and Cook was killed at the water’s edge at Ka‘awaloa. In the tense aftermath, a young ali‘i named Kamehameha was among those who sent hogs onboard to smooth relations.

Cook left behind journals and maps that highlighted Hawai‘i as a key provisioning stop for trading ships crossing the Pacific. His expeditions also produced a trove of ethnographic images, cultural artifacts and botanical specimens that brought Hawai‘i and the Pacific to world attention. Yet Cook and other explorers left a more troubling legacy of disease in the islands that would decimate the Hawaiian people.

— Secret Admiralty instructions to Cook, July 30, 1768

2Kamakau, Samuel M., Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii, Revised Edition, p. 101. Note: Kalani‘ōpu‘u’s cape and helmet are on display at Bishop Museum.