For Hawaiians, land was not something to be bought and sold but a living ancestor. The ali‘i and common people shared in the duty to mālama ‘āina, to care for the land, though commoners bore the brunt of the heavy labor. By practicing mālama ‘āina, the land would reciprocate by fulfilling their needs.

— Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa, Native Lands and Foreign Desires, p. 25

‘Āina

- The ali‘i controlled the ‘āina, but they did not own it. After a ruling chief’s death, lands under his command reverted to his successor, who re-distributed them among his most loyal followers. This practice, called the kālai‘āina, cemented an ali‘i’s right to rule.

- The maka‘āinana resided on the lands, doing all of the work, yet the yield they produced all belonged to the ali‘i.

— David Malo, Hawaiian Antiquities, p. 61

Finding Pono

- For Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III), the question topmost in his mind was how he might become a pono leader1 and restore harmony to a nation buffeted by foreign conflicts.

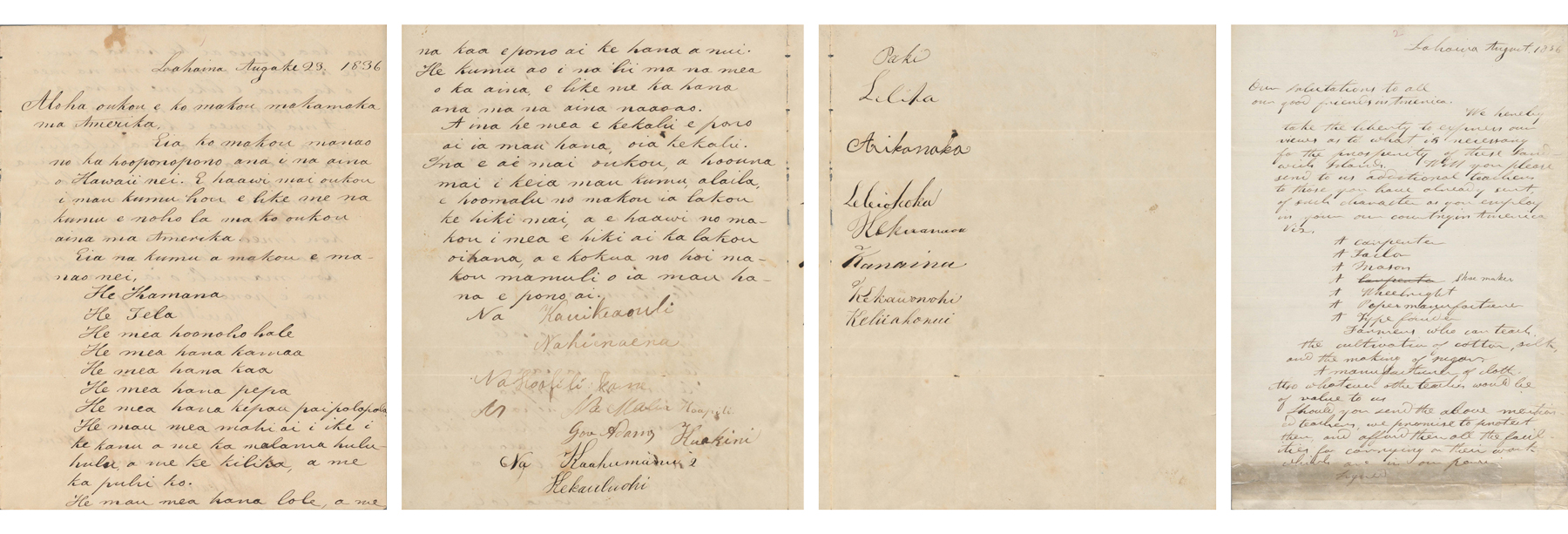

- This is reflected in an 1836 letter the king and his chiefs wrote, on the advice of the missionaries, asking ABCFM to send them teachers. The letter requested one teacher in particular: “He kumu ao i na ‘lii ma na mea o ka aina, e like me ka hana ana ma na aina naauao. (A teacher for the chiefs in matters of land, comparable to what is done in enlightened lands).”2

- Kauikeaouli chose the path laid out by his two mothers, Keōpūolani and Ka‘ahumanu. Under his rule, pono would arise from the twin pillars of Christianity and Western law rather than from traditional sacred beliefs.

— Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa, Native Lands and Foreign Desires, p. 167

1 Kame‘eleihiwa, Native Lands and Foreign Desires, p. 49.

2 Letter dated August 23, 1836. Signed by Kauikeaouli, Nāhi‘ena‘ena, Hoapilikāne, Malia Hoapili, Gov. Adams Kuakini, Ka‘ahumanu II, Kekāuluohi, Paki, Liliha, ‘Aikanaka, Leleiohoku, Kekūanāo‘a, Kana‘ina, Kekau‘ōnohi, and Keli‘iahonui.