Preparing students for a rapidly changing world

Twelve years ago, I started a Science Fiction class in the Academy, and I’ve been teaching it ever since. We cover four units: Time Travel, Utopia/Dystopia, Artificial Intelligence, and Outer Space. Certain ideas that felt highly speculative and gee-whiz just a decade ago are now in our face. Augmented reality! Self-driving cars! AI that can carry on conversations and make art! Fantastical though these technologies seem, our world is increasingly filled with them.

As a father, educator and sometimes futurist, I believe in the transformative power of technology, not least because I have two children who can hear thanks to cochlear implants. AI in particular has the potential to improve our lives in countless ways – medically, environmentally, even economically if we play our cards right. But it would be disingenuous of me not to recognize the magnitude of the challenges we face: Planet Earth smashes heat records year after year, dozens of species go extinct every day, AI experts sound the alarm about Frankensteinian threats posed by their own creations, social inequities fester … and the list goes on.

In taking stock of all this, I draw two working conclusions. First, there is no silver bullet that will extricate humanity from the situation we find ourselves in. Because these challenges are so vast and complex, we will need an integration of disciplines. STEM will remain essential, but as technical obstacles fall, the questions we face as a species will be of an increasingly existential variety. What does it mean to be human? And what – as individuals, members of communities, earthlings – do we value? In a world where we are teaching those values not just to our children but to increasingly intelligent machines every time we interact with them, such questions have never felt so vital. The clear divisions we erect between our various disciplines – science, philosophy, art, etc. – are likely to look more and more porous.

My second conclusion is really another way of stating the same thing: No lone genius-hero is likely to save us. If humans are to flourish in coming centuries and beyond, it will be as a result of recognizing how interconnected we all are, and of coordinating our talents and interests to solve our most complex problems. A mat that seats many – with people of diverse backgrounds and skill sets – will be essential.

Schools, and education more broadly, can play a central role in fostering the types of mindsets the future will surely require. In this issue of the Bulletin, we explore how Punahou is doing its part in supporting students to think through these challenges and harness their creativity, technical know-how and interpersonal skills to generate potential solutions one day.

From the outset of Punahou’s educational journey, students are given opportunities to work collaboratively. Through the Rainbow of Learning Lessons, for example, kindergartners build their listening skills, sharpen their ability to exchange ideas with classmates and finesse the art of negotiation and compromise. Meanwhile, the Davis Democracy Initiative, which launched earlier this year, inspires youth to become better informed, socially engaged citizens.

Classes with multidisciplinary projects – such as Climart, which utilizes scientific data points to create art with a message around climate change, and Biomimicry, in which students study how nature works to conceptualize solutions around human problems – are showing students the power of integrating art, science and design. And a host of other courses, including our Global Sustainability by Design (GSD) classes, challenge students to look at complex problems from multiple perspectives and to think holistically about solutions.

For most of human history, parents could feel reasonably assured that their children’s lives would look something like their own. From here in 2023, amid accelerating rates of change on multiple fronts, it’s hard to know what human life will look like next year, let alone a generation from now. Still, we have reason to feel optimistic. This may be an all-hands-on-deck moment for our species, but just look at all these capable hands.

By Tom Gammarino

Illustrations By Isabel Cheever ’23

Punahou English Faculty, Author

Gammarino leveraged his talents as a seasoned educator and science fiction writer to pen the special introduction in the “Future Forward” cover story. Gammarino has taught English at Punahou for 14 years and is a respected novelist and author of many short stories and essays. His recent work has appeared in “Interzone,” “World Literature Today” and “Utopia Science Fiction.” He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from The New School and a PhD in English from the University of Hawai‘i, and has received a Fulbright Fellowship and the Elliot Cades Award for Literature.

Student Artist

Cheever did not use conventional creative design tools to draft the vibrant art gracing the cover of the Punahou Bulletin – instead, she used artificial intelligence to translate her words into images. What did this process entail? Cheever started by familiarizing herself with the thesis of the “Future Forward” story. She then logged onto Midjourney – a generative AI platform – and wrote words and sentences pertaining to the theme of the article. The program interpreted her text and produced the unique artwork.

“If humans are to flourish in coming centuries and beyond, it will be as a result of recognizing how interconnected we all are, and of coordinating our talents and interests to solve our most complex problems. A mat that seats many – with people of diverse backgrounds and skill sets – will be essential.”

— Tom Gammarino, English Faculty

Reality Check: Blending Art and Science to Raise Awareness About Climate Change

By Noelle Fujii-Oride

Lau incorporated art and scientific data to develop a drawing foreshadowing the impact of rising ocean temperatures on our way of life. Her multidisciplinary project uses a line graph of ocean heat content from 1955 – 2020, published by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Haley Lau’s ’27 love for the beach led her to insert a line graph of rising ocean temperatures into her work of art depicting the causes and effects of this phenomenon.

“The interesting part about this project is that it wasn’t just art and it wasn’t just science,” Lau says of her eighth-grade science Climart project. “I thought it was very unique that we could incorporate the actual graph with the data into the art piece. I feel like it gives it more meaning.”

All eighth graders spend a month working on their Climart projects while they study biology. Through this multidisciplinary unit, students blend historic scientific data with the sensory power of art to create visual projects that convey poignant messages about the state of our environment.

The unit was inspired by climate scientist and artist Jill Pelto whose work focuses on communicating the connections between humans and the environment. Punahou’s eighth-grade science department created their own version of a Climart project by modifying a Science Friday lesson plan that highlighted Pelto’s artwork.

“By embedding the data points into the work of art, the idea is to make climate change more relevant and better communicate the important impact that it’s having in the world,” says Allison Rodden-Lee ’00, eighth-grade science teacher and middle school department head.

“The science behind sustainability and teaching it is very multidisciplinary,” she says. “It’s not its own sort of silo. It weaves in lots of different science areas as well as social studies.”

Lau’s artwork focused on a line graph of ocean heat content from 1955 – 2020 published by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The graph depicts joules calculated using different methods by government agencies in four countries. They are compared to the 1971 – 2000 average.

Using color pencils, Lau wanted to document the ripple effect that small actions can have on the environment. As the ocean’s temperature rose, she showed healthy, vibrant coral becoming bleached, and fish becoming less abundant. She also drew hands holding a melting glacier and a smoggy city to show that rising ocean heat content is largely caused by greenhouse gases emitted from human activities.

“When we’re doing things like using more electricity than we need or using too much gas, which increases the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, it also impacts the ocean and it creates things like excessive storms and unpredictable weather,” she says. “And it all just connects, creating a cycle that doesn’t really stop.”

She says she found it interesting to see how activities across the world connect to daily life for the average person: “These small things we do … when you add it up, it has such a huge impact and it’s all coming back at us.”

Rodden-Lee’s eighth graders wrote artist statements explaining why they picked their subjects, how it was relevant to them and the science behind their data. She says she wanted her students to build on their analytical and critical thinking skills.

“They’re the new generation that’s going to have to figure out how to make some real changes so that we can sustain ourselves on the planet,” she says.

She adds: “When you read their reflections, you can start to see how what they’ve been researching starts to kind of click in their brain and starts to hit home and gets their wheels spinning on what might their next steps be or what might they do in high school to explore ideas further.”

It All Starts Here

By Carlyn Tani ’69

Being able to work effectively in diverse teams will be essential to tackle the complex challenges of tomorrow. Students are given ample opportunities to work collaboratively – whether through gardening, math exercises or design thinking projects – from the start of their educational journey at Punahou.

On a bright spring morning, 25 first graders settled onto the carpet in front of Lauli‘a Phillips ’98 Ah Wong, K – 5 counselor, and learning support specialist Danielle Mizuta, for a lesson on kuleana, or responsibility. The two read aloud a delightful story about a humpback calf, named Na‘auao, who was alienating everyone around him with his thoughtless, self-centered behavior. After listening to the story, the children paired up to brainstorm how Na‘auao could use forethought and insight to take responsibility for his tattered social relationships. As the youngsters traded ideas, they practiced responsible decision-making by weighing the social consequences of individual behaviors. They also employed critical competencies, such as listening attentively, taking turns and sharing ideas, negotiating and showing empathy for others – skills that foster a child’s budding sense of self and others.

The half-hour session is part of Punahou’s Rainbow of Learning Lessons, created by Ah Wong and Mizuta and utilized in grades K – 3. This curriculum empowers students in a multitude of ways, not the least of which is helping them build the skills for working effectively in groups; a core element of complex problem-solving that will be essential not just during their tenure at Punahou but also throughout their careers.

Children learn to disagree respectfully while inviting different points of view, and to negotiate conflict. Appreciating diversity and showing respect for others enhance social awareness, Ah Wong says. “Throughout a student’s journey at Punahou and beyond, they will engage with different peers and groups, and when students are able to accept different perspectives, they’re valuing that person’s identity and experiences. And when we value each other’s identity, we know that we belong.”

The weekly lessons, which reflect Punahou’s character values, are built upon CASEL, a framework that identifies competencies to promote social and emotional learning, and the RULER program. The RULER approach teaches children to Recognize, Understand, Label, Express and Regulate their feelings, validating the full spectrum of emotions.

“It’s important that kids can identify strategies to help themselves manage big emotions,” Ah Wong explains, “because if they have that early foundation in social, emotional and ethical learning (SEEL) skills, it’s something they’ll use over time.” Research affirms that healthy social connections bolster a child’s learning and overall sense of well-being.

For Ah Wong, her work with early learners has personal meaning. As a native Hawaiian student during the ’90s, she often struggled at school to connect with her identity. This experience, she recalls,“really helped me understand that children need to feel that they belong.” Today, Ah Wong is applying her experience not only to nurture the SEEL skills that shape a child’s well-being – but also to equip a new generation of leaders with the aptitude to confront the complex issues of tomorrow.

The Rainbow Lessons provide students with a toolkit for managing feelings.The Mood Meter, a multi-colored quadrant, helps them assess their emotional state; the Charter creates a shared understanding of how children want to be together at school; and the Meta Moment introduces self-management techniques, including deep breathing and mindfulness. Teachers in grades 4 – 5 also have embraced the approach in their classrooms, according to Principal Todd Chow-Hoy. “As a community, we’re using the same words and responding more consistently so that as a student moves through those early years, they’re aware of what their responsibility is when something doesn’t go right.”

Laying the groundwork for principles like working effectively in teams, building a sense of kuleana and sharpening social and emotional skills will have a lasting impact not just for the students, but also for our community. “One of the things that distinguishes us as a school is that we spend a lot of time with these social skills,” says Chow-Hoy. “It’s not just about academics. We’re also cultivating the skills that will enable our children to contribute to society, to work with different people and to lean into difficult conversations with a high degree of grace and understanding. And this is where it all starts.”

Mimicking Mother Nature

By Noelle Fujii-Oride

Punahou’s sixth grade science curriculum culminates in a month-long Biomimicry unit, which challenges students to find answers to some of today’s most daunting problems – by turning to nature.

“Biomimicry is designing structures and systems that draw inspiration from how nature works. In emulating biological designs and processes to create sustainable solutions, you can really help solve challenges related to sustainability – and you’re not compounding the issue with your solution,” says Zoe Namba ’12, sixth-grade science faculty.

This year, the Biomimicry unit began with an assembly featuring Dan Kinzer, lead community technologist at Purple Mai‘a. He spoke about the ways in which the local nonprofit has implemented biomimicry in real life.

Students worked in small groups and selected a problem related to climate change that tied into one or more of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Altogether, there are 17 SDGs, which include no poverty, zero hunger, clean water and sanitation, affordable and clean energy and quality education.

Camille Inouye ’29 and Isabel Pearson ’29, students in Ms. Namba’s class, sought solutions to a critical problem: ending hunger in developing countries. But the catch was that they wanted to avoid solutions that use open fires for cooking because they emit carbon into the atmosphere – and exacerbate climate change.

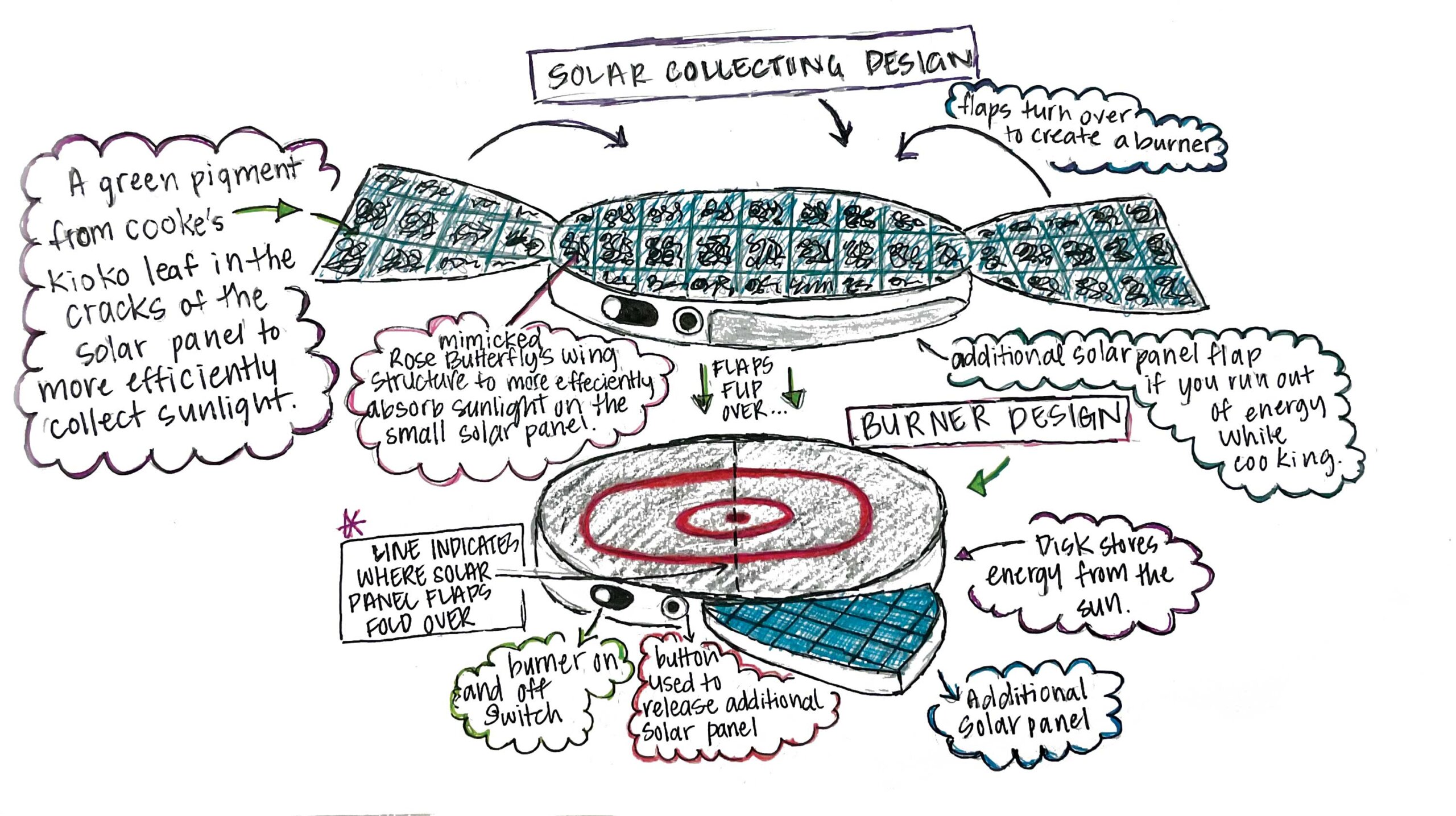

“We wanted to find a way to create renewable energy that was good for the environment,” Inouye says. The pair researched a variety of plants and animals that could inform their design of a solar-powered grill. They ultimately settled on the Cooke’s koki‘o, a rare and endangered plant endemic to Moloka‘i, and the rose butterfly. By combining elements from the plant’s green pigment and the butterfly’s interlaced wing structure, they designed a way to increase the efficiency of the grill’s solar panels.

“We learned about the ways in which animals have evolved and solved problems in their particular environment – and we were tasked to put that into the perspective of an engineer,” Pearson says.

Inouye and Pearson named their solution “Da Solar Steak.” The circular grill has solar panel flaps that – much like the wings of a butterfly – can open to absorb sunlight. A green pigment lines the cracks of the solar panel, forming a grid with solar cells that mimic the rose butterfly’s wing structure in between.

They wrote reflections on their learnings and created an advertisement board and video to showcase their designs. Namba says the advertisement board and video encouraged her students to hone their creativity, communication, collaboration and technology skills.

The students voted on the best ideas within their team spaces, and Inouye and Pearson’s video was one of six shared at the end-of-the-year sixth-grade assembly.

Other students’ ideas included projects like a more efficient and sustainable waterwheel, a reusable bag, a compost creator and an airplane. “I learned that I can help think of ideas that can change the world,” Inouye says.

Namba says she’s enjoyed seeing the students get excited about their ideas. “It’s really awesome to just watch their excitement fuel their learning and just to hear them be like, ‘Oh my god, have you gone to science class yet because this project will be so fun?’” she says.

She and her colleagues plan to continue the Biomimicry project next year, though they want it to have a stronger connection to Hawai‘i. That could mean focusing on Hawai‘i-specific problems or finding inspiration from native or endemic plants or animals. She hopes her students understand they can use what they’ve learned in class to help their community.

“Our world is changing. The amplifications of climate change are increasing and I do think it is our students’ kuleana to do something, to do their part,” she says.

Taking Center Stage

By Carlyn Tani ’69

For Irene Zhong ’24, activism and the performing arts are rooted in the same human impulse: understanding others. She’s finding success in both; last year, the 17-year-old reigned as Hawai‘i’s Poetry Out Loud state champion and placed second nationally in the competition’s written poetry match, all-the-while earning school awards for spearheading an Academy initiative on restorative justice.

“Performing arts allow me to empathize with others because I have to adopt many different roles,” she explains. “But activism is also a channel for empathy because it requires me to give myself to those I’m working with.”

Zhong embodies the notion, extolled by poet Walt Whitman, that one person can “contain multitudes,” an essential trait for tackling the complex challenges we are facing. As a sophomore, Zhong was propelled into social action after witnessing the alarming decline of civil discourse in American politics.“It’s extremely politically polarized today, and seeing this deep divide in ideas frustrates me because we all want the same thing: to live together with compassion and respect,” she says. Her parents, who emmigrated from Chang Zhou, China, encouraged Zhong and her twin sister Ivey ’24 to help others. “My parents came to a new country and were welcomed here so they want us to be welcoming toward others, too. And giving back to our community is just part of Punahou’s education.”

Punahou opened a world of opportunities for this self-described “shy kid.” After entering in fourth grade, Zhong joined the chess club, took up violin and later pursued symphony orchestra, speech and acting in the Academy. The willowy, soft-spoken senior transforms into a powerhouse onstage. Her Poetry Out Loud recitation of “The Coming Woman” by Mary Weston Fordham, a Civil War-era educator, reformer and a free woman of color, offered an acerbic portrait of women’s lives during that tumultuous period.

At the beginning of 10th grade, Zhong was not familiar with social justice or activism. “I remember during our first meeting with Dr. Dave Ball (Academy English faculty and Davis Democracy Initiative program coordinator) he asked: ‘What is one issue you see today that you wish could be changed?’ I was shocked to hear such a hard-hitting question right off the bat because I wasn’t accustomed to talking about sensitive topics,” she recalls. “But the more work I did with Dr. Ball, the more I realized that that type of self-driven and bold attitude was required of people who want to make a change.”

Zhong joined the Shanti Alliance, an organization that promotes inclusive environments in schools. Her six-member Shanti cohort worked two years to design and pilot a program on restorative justice.

Originating in prison reform, restorative justice facilitates a discussion between the affected parties with the aim of repairing the harm done in a holistic rather than punitive manner. For example, if a student were caught plagiarizing, typical punishment might consist of assigning demerits, some of which could be worked off by doing unrelated tasks on campus. This addresses neither the teacher’s loss of time and trust nor the student’s breach of conduct. With restorative justice, the teacher and student would agree to meet within the framework of exploring the question: “How can we heal the harm done?”

The Shanti cohort’s lessons were well-received by ninth graders in Support + Wellness’ SURF-1 classes. Additionally, 9th grade deans began incorporating elements of restorative justice in handling disciplinary matters. “We felt that this approach was so much more effective for our class in learning to be a respectful community together,” explains Wendi Kamiya, Academy Dean. Kamiya attributes the Shanti cohort’s success to Zhong’s inclusive leadership style. “Irene lets everyone else shine, because she realizes that it’s not about her – it’s about the work and the outcome.”

When Zhong steps on stage, she often feels a mixture of gratitude and excitement. “I hope my voice elevates the words, scoops out the emotion and moves the audience to feel something,” she says. The multi-talented teen will also continue to raise her voice for a more holistic approach to justice and life. “Restorative justice is a way to heal relationships and maybe from there we can slowly heal the deep political strife between people.”

Augmented Connections

By Noëlle Nakaoka ’20

Mahina Hardin ’23 felt unsettled witnessing the impact that invasive algae were inflicting on the coral gardens she grew up frequenting in her beloved Kāne‘ohe Bay, so she went into action. Along the way, she has worked in tandem with local environmental non profits; attained a Distinction from the Case Accelerator for Student Entrepreneurship (CASE) and, most recently, turned her passion for protecting Hawai‘i’s irreplaceable coral ecosystems into a business.

“The purpose of the CASE Distinction in Student Entrepreneurship is to offer a framework for students to tackle a big challenge they care about, develop their unique solution and ultimately learn how to turn what they enjoy doing into a career,” says Director Mark Loughridge. “Mahina’s work is an outstanding example of this. She is opening up new vistas in how students can learn and she meets the challenge of coral reef preservation head on with thoughtfulness and creativity.”

Her work produced “Into the Ecosystem” which is a development studio that Hardin is cultivating into a subscription-based platform, working with schools and other educational organizations to create apps for their curricula.

Leveraging augmented reality, “Into the Ecosystem” breaks down the walls of the classroom and transports students into an immersive adventure. Using their iPads, students virtually experience moving among the Hawaiian reef with corals growing along the floor and fish swimming around. They collaborate to identify invasive species, discover the sources of pollution and take action to restore the reef to health.

“Compared to traditional methods of spreading awareness, our apps actively stimulate students’ senses, giving them an authentic experience as they work together to identify real-world threats to an ecosystem,” says Hardin. “We aim for the experience to leave a lasting emotional impression, encouraging and educating youth to take action.”

Getting to this point has taken years of work and commitment. Her journey began in 2020, when she was introduced to computer science through a class called Coding for Social Change – a course developed by CASE and taught by Greg Mittleider, who served as Preceptor in Computer Science for Harvard University. Hardin and her classmates experimented with cutting-edge tools such as artificial intelligence and blockchain, discussed global and local challenges they see across the world – then rolled up their sleeves to code their prototypes and address their chosen challenges.

“Our younger generations are inheriting extraordinary challenges that will require unprecedented innovation, creativity and collaboration to solve,” says Loughridge. “This course empowered our Academy students to build the algorithms and prototypes to demonstrate new solutions to these multifaceted problems and new paths forward for systems change.”

“Into the Ecosystem’s” first production yielded an app for Ma¯lama Maunalua, a non-profit entity that educates youth on how to protect the bay from rapid alien algae invasion. The app, dubbed “Into Maunalua Bay,” offers users a detailed view of the ecosystem’s magnificent coral garden, complete with swimming fish, vegetation and a turtle. They are prompted to find potential solutions for the growing population of invasive algae. The user then opens a toolbox with choices to combat invasive algae and prevent it from taking over the habitat.

Left: Mahina Hardin ’23 uses augmented reality to generate lasting emotional experiences that inspire young learners to connect with the environment – and think of creative approaches to preserve treasured ecosystems.

Right: Hardin’s app shows a detailed view of Maunalua Bay’s coral ecosystem, with an up-close look at invasive algae, including leather mudweed and gorilla ogo.

During her senior year, Hardin was booked and busy with the development of this new app and learned the value of efficient project management. Every Wednesday, she would meet with an XR design and Meta Software developer to grow her Unity programming skill set. Every Tuesday and Thursday, she would collect feedback from fourth grade students participating in Game Academy, a CASE Co-curricular program where students work in Scratch, a block-based visual programming language to create their own games.

“Working with the fourth graders inspired a lot of the creative aspects for the app,” says Hardin. “I’ve observed that young students value creative autonomy and being able to put their own spin on things. This knowledge has influenced the concept of ‘Into Maunalua Bay’ since my goal is to increase their engagement and motivation to learn.”

She is now attending Oregon State University planning to major in computer science. Her goal for the younger generation is to experience coral reef systems as she did during her childhood and to continue developing “Into the Ecosystem” throughout college.