Russian artist Louis Choris drew a portrait of “Tammeamea” on November 24, 1816, the day the Rurik anchored in Kailua Bay. The better-known version shows Kamehameha in a red vest, but Choris published this altered portrait in 1822 after Kamehameha had died. Kamehameha, King of the Sandwich Islands, watercolor by Louis Choris, Honolulu Museum of Art.

King Kamehameha I united the Hawaiian Islands at a time when foreign influences were transforming everything around him. He managed the difficult feat of preserving traditional Hawaiian beliefs while exploiting the economic benefits of modern trade.

Kamehameha was born to Keku‘i‘apoiwa, a Maui chiefess, in North Kohala during the 1750s. His father Keōua was the half-brother of Kalani‘ōpu‘u, ali‘i nui of Hawai‘i Island. As a young man, Kamehameha received special training from his uncle Kalani‘ōpu‘u and grew into a skilled, fearsome warrior. When Kalani‘ōpu‘u died in 1782, rival ali‘i mounted a series of battles for control of Hawai‘i Island that Kamehameha ultimately won.

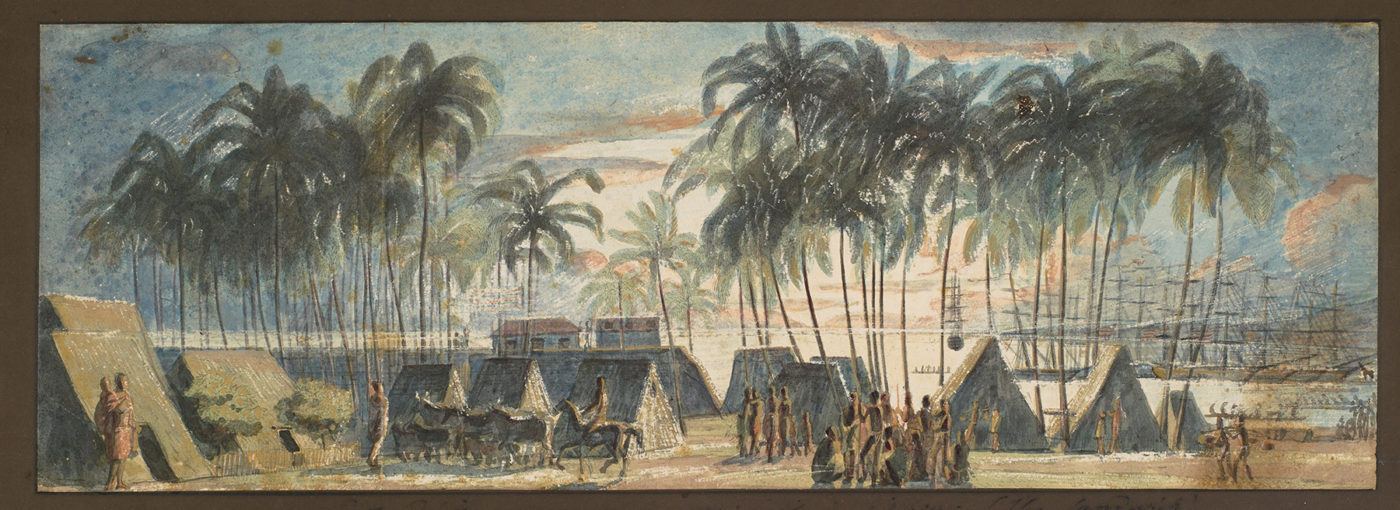

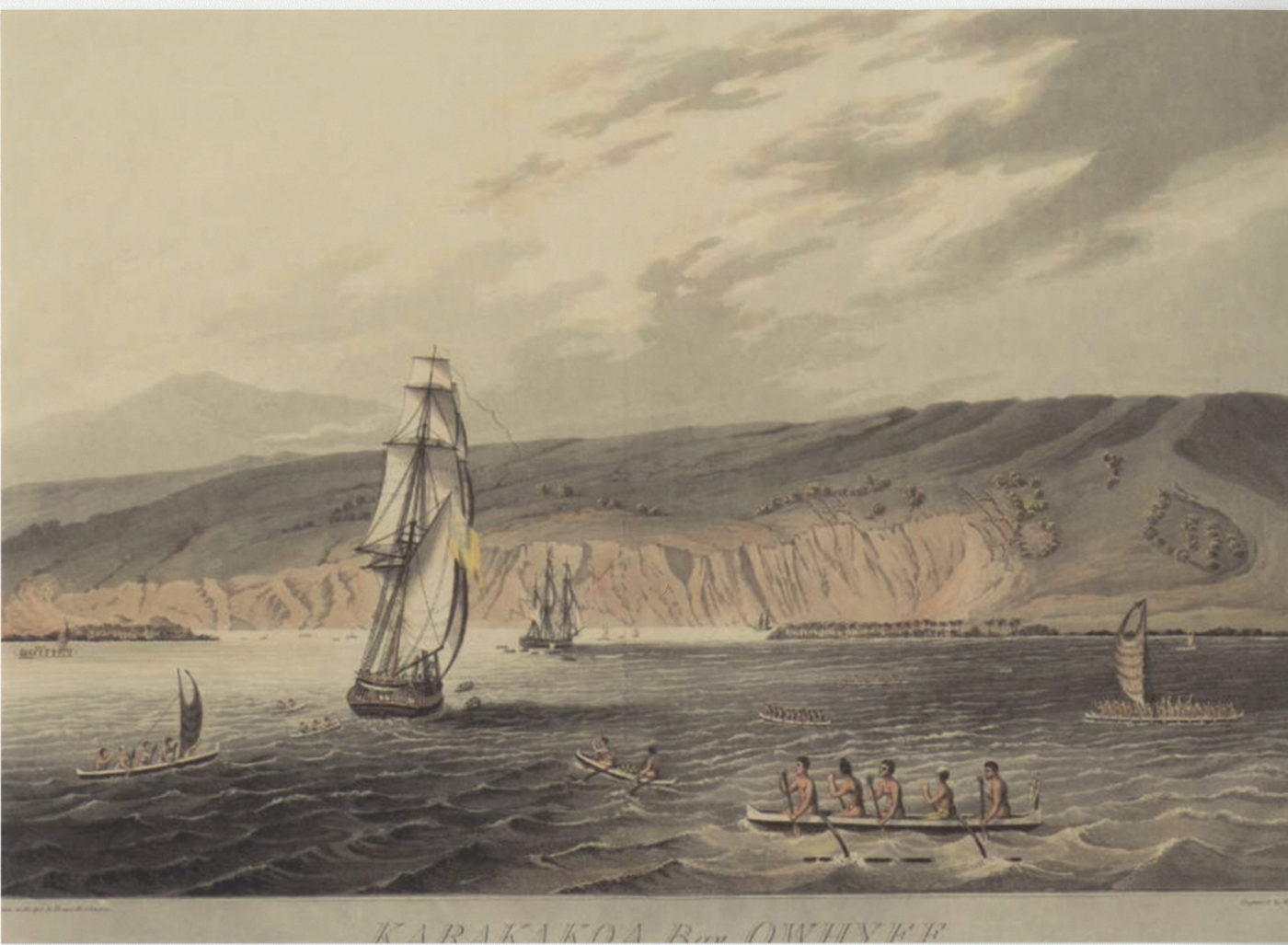

At the time, Hawai‘i was becoming a global shipping hub. From 1786 to 1799, forty-five different foreign vessels entered Hawaiian waters,1 impressing upon Kamehameha the islands’ vulnerability to a foreign takeover. In 1794, he ceded Hawai‘i Island to Great Britain in exchange for military protection. In a ceremony on board the HMS Discovery, on February 25, an assembly of chiefs witnessed Kamehameha’s treaty with Captain George Vancouver.2 Hawai‘i ali‘i expected Britain, which had the world’s leading navy, to deliver ships and men to the islands, but the agreement was never ratified by British Parliament. Still, other countries believed the treaty was in force, which effectively shielded Hawai‘i from foreign incursions for the next 30 years.

Kamehameha took up his decades-long campaign to unite the islands. The 1795 Battle of Nu‘uanu was a turning point in eliminating powerful rivals and bringing the bountiful agricultural lands of O‘ahu under his rule. With an army of 12,000 men and a fleet of 1,200 war canoes, Kamehameha chased the rival forces, led by Kalanikūpule, to the back of Nu‘uanu Valley where 800 defending warriors leapt from its sheer cliffs to their death. Kamehameha had benefited from a superior cache of modern weapons, including a cannon, and the counsel of foreign advisers John Young and Isaac Davis. After the battle, the king awarded Kame‘eiamoku, his loyal ali‘i, the spring-fed lands of Kapunahou, which later became home to Punahou School.

In 1810, Kaumuali‘i ceded Kaua‘i to Kamehameha, formally bringing all of Hawai‘i under one ruler for the first time. Kamehameha wrested control of the sandalwood trade from the ali‘i, who had used it to acquire weapons, ships and exotic goods, by establishing a royal monopoly. He also imposed a kapu on young ‘iliahi trees, allowing them to recover from overharvesting. The sandalwood kapu is one illustration of how Kamehameha and other ali‘i had begun to apply the religious principle of kapu to more secular aims.3 Under Kamehameha, unification of the islands ushered in an era of peace and political stability.

E piʻi ana o lalo

E hui ana nā moku

E kū ana ka paiaThat which is above shall be brought down

That which is below shall be lifted up

The islands shall be united

The walls shall stand upright

— A chant by Kapihe of Kona, Hawai‘i, prophesizing the unification of the islands.4

2Vancouver presented Kamehameha with a Red Ensign flag, flown by British merchant ships, which later was incorporated in the Hawaiian flag.

3Not all royal kapu were beneficial. In 1793, at Kawaihae, Captain Vancouver gifted Kamehameha with five cows, two ewes and a ram, and later supplemented the gift with bulls. At Vancouver’s urging, Kamehameha placed a 10-year kapu on the slaughter of these animals, which proliferated across the Islands. They ran wild and stripped the forests and lands of vegetation, hastening the decline – and extinction – of Hawai‘i’s endemic birds, snails and insects.

4Malo, David, Hawaiian Antiquities, Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, 1951, p. 115.