From the time of Captain Cook, Hawaiians saw that foreigners used writing to both formalize agreements and communicate ideas. But the fleeting nature of foreign interaction did not allow Hawaiians to acquire this powerful tool for themselves. In 1820, when the first missionaries met with Liholiho (Kamehameha II), they promised to teach reading and writing, should he allow them to stay. The King accepted their tantalizing offer, which would solidify the missionaries’ role in Hawai‘i and elevate Hawai‘i as one of the most literate nations in the world.

Teaching the Ali‘i

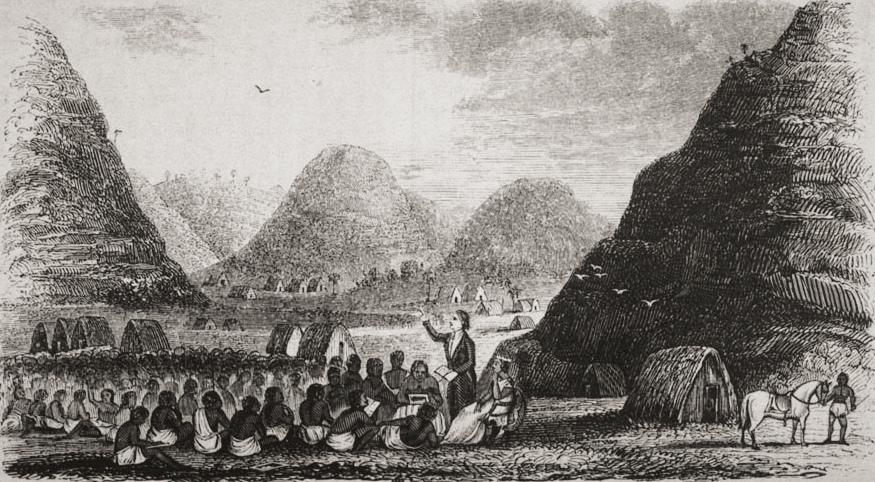

- Liholiho ordered the missionaries to instruct the ali‘i first in reading and writing (palapala). As a result, missionaries gained unprecedented access to the chiefs and their households, thereby boosting their influence.

- Through teaching sewing or reading and writing, the missionaries, unlike other foreigners, were “providing skills the ali‘i wanted for themselves and for their people.”4

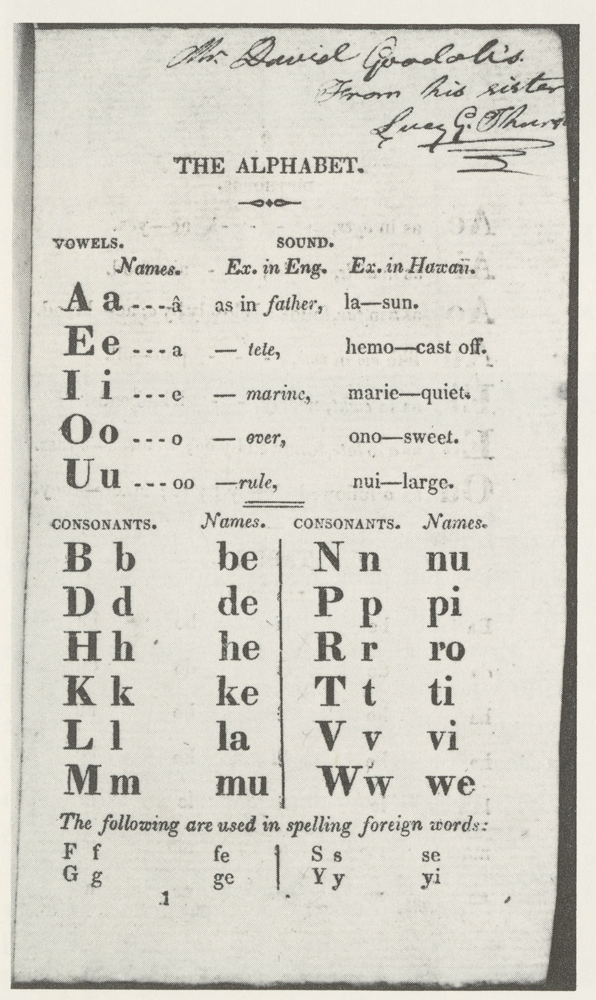

Printing the Pīʻāpā

- The missionaries first taught in English, using interpreters, but worked to realize their goal to teach in Hawaiian. In 1822, the first 500 copies of the pīʻāpā Hawaiʻi, or Hawaiian alphabet, came off the Mission’s printing press. The pamphlet was snapped up immediately, generating even greater demand.

- Rev. Bingham presented Ka‘ahumanu with the new pīʻāpā and highlighted the alphabet for the Queen. “She was induced to imitate my voice in their enunciation of a, e, i, o, u.” Within ten minutes, Ka‘ahumanu could read and pronounce the vowels in order. “Ua loaa iau! I have got it,” she exclaimed, ordering 40 copies for her household.5

— Missionary letters (unpublished), vol. 2, p. 316 (as reported in Laimana6)

Literacy Explodes

— Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) in a speech in 1825 at 11 years of age7

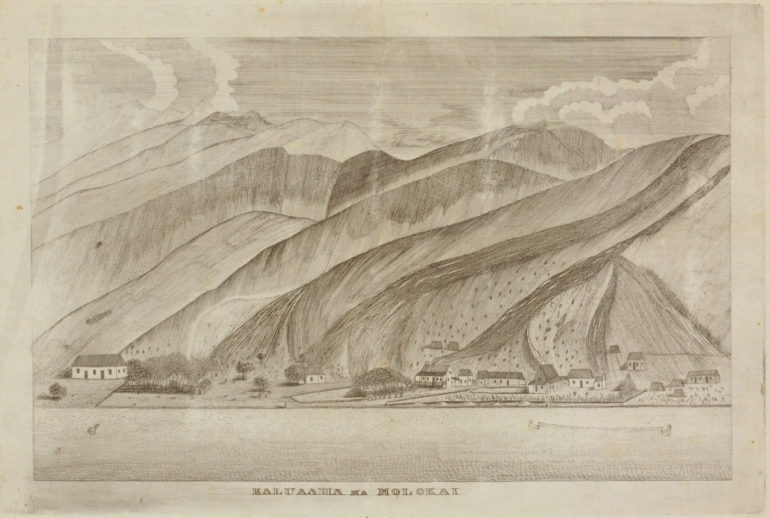

- The Hawaiian government mounted a large-scale effort to build schools for commoners while the missionaries struggled to train enough teachers. By 1831, “the number of common schools throughout the kingdom was about 1,100, and the number of pupils about 52,000, approximately two-fifths of the entire population.”8 Most of the initial students were adults.

- The missionaries set up quarterly literacy exams. These public, two-day events featured rigorous tests in reading, writing, composition and oratory. Students traveled as far as 14 miles to attend. In 1831, a staggering 10,000 students underwent one such examination.

- By 1834, Hawai‘i’s literacy rate had soared to 91 percent.9 During that same period, literacy in the United States was 78 percent while European nations claimed 50 percent or less.

- How did Hawaiians achieve such an astonishingly high level of literacy? Several factors were key:

- Ali‘i sanctioned and actively advocated for the palapala;

- The pīʻāpā was printed and distributed widely, while missionaries trained a cadre of local teachers;

- Hawaiians were eager and adept learners.

— John Laimana, “The Phenomenal Rise to Literacy in Hawai‘i”, p. 30

Literacy would have a profound effect on Hawaiian society. Beyond its proselytizing effect, literacy ensured that knowledge no longer belonged to the ali‘i alone. This leveling of knowledge across different classes served to accelerate the rise of Hawaiian-language newspapers.

4 Arista, Noelani, The Kingdom and the Republic, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2019, p. 124.

5 Bingham, Hiram, “A Residence of Twenty One Years in the Sandwich Islands,” Praeger Publishers, NY, 1969, pp. 164 – 165.

6 Laimana, John Kalei, “The Phenomenal Rise to Literacy in Hawai‘i,” master’s thesis, UH Mānoa, 2011.

7 Kamakau, Samuel, Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, October 3, 1868. English translation in Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs of Hawai’i (Revised Edition), Kamehameha Schools Press, Honolulu, 1961, p. 319.

8 Kuykendall, p. 106.

9 Laimana, p. 10