By Catherine Black ’94

Jeff and David are seniors and good friends. They’ve attended Punahou since kindergarten and play water polo together. But over the years, David has noticed some growing differences between them. Jeff is one of the “smart kids.” He has always taken honors and AP classes, even in the summer. David, on the other hand, is only in math honors — a subject he loves — and two AP classes. In addition to water polo, Jeff is on the varsity track and field team. He is the president of two clubs (one of which he founded) and usually has a role in the spring theater musical. He was a booth chair at Carnival and volunteers at Queen’s Hospital on the weekends. David is on the editorial team of Ka Wai Ola because he loves underwater photography, but that’s his main extracurricular. The two friends used to surf together at least twice a week, but now David is lucky if he sees Jeff once a month.

He knows it’s not for lack of affection; his friend just doesn’t have any time. He often receives text messages from Jeff after midnight and he knows it’s because Jeff is up studying after a long day of activities that rarely end before dinner. One day, seeing his friend pop some caffeine pills before a test, David suggests he take something off his plate and sleep more. “Sleep is for wusses who don’t want to go to Harvard,” replies Jeff offhandedly. David wonders if he is a “wuss” for not wanting to go to Harvard.

When early acceptance letters arrive, Jeff is wait-listed for Harvard but accepted at Yale. “That’s awesome, dude!” says David, giving him a slap on the back. “Yeah, I guess so,” is Jeff’s lukewarm response. “But if I don’t get into Harvard with regular admissions, my parents are going to kill me.”

In a culture accustomed to ranking people by their external achievements, Jeff is often grouped with the winners. However, there are important differences between Jeff and David that are not so easy to see: Jeff suffers from anxiety, sudden bouts of depression, chronic lack of sleep and a growing inability to share his emotional insecurities with others. David, on the other hand, is a happy kid. He is physically healthy and sees direct links between school and his personal interests (surfing combines his love of photography and his fascination with physics).

Jeff and David are fictional Punahou students, but their stories are not unusual. Which of them would you want your child to be? More to the point, who would you rather be?

Of course, there is no right answer to these questions, but the panorama in which they are asked has been changing. Not long ago, high school was a fairly straightforward preparation for college, which was a fairly straightforward preparation for an established profession. Today, this formula has been punctured in so many places that neither is the best Ivy League a guarantee of success in an innovation-based economy, nor do high marks at a good private school reveal the resilient character and creative, critical thinking that many top colleges look for in prospective students.

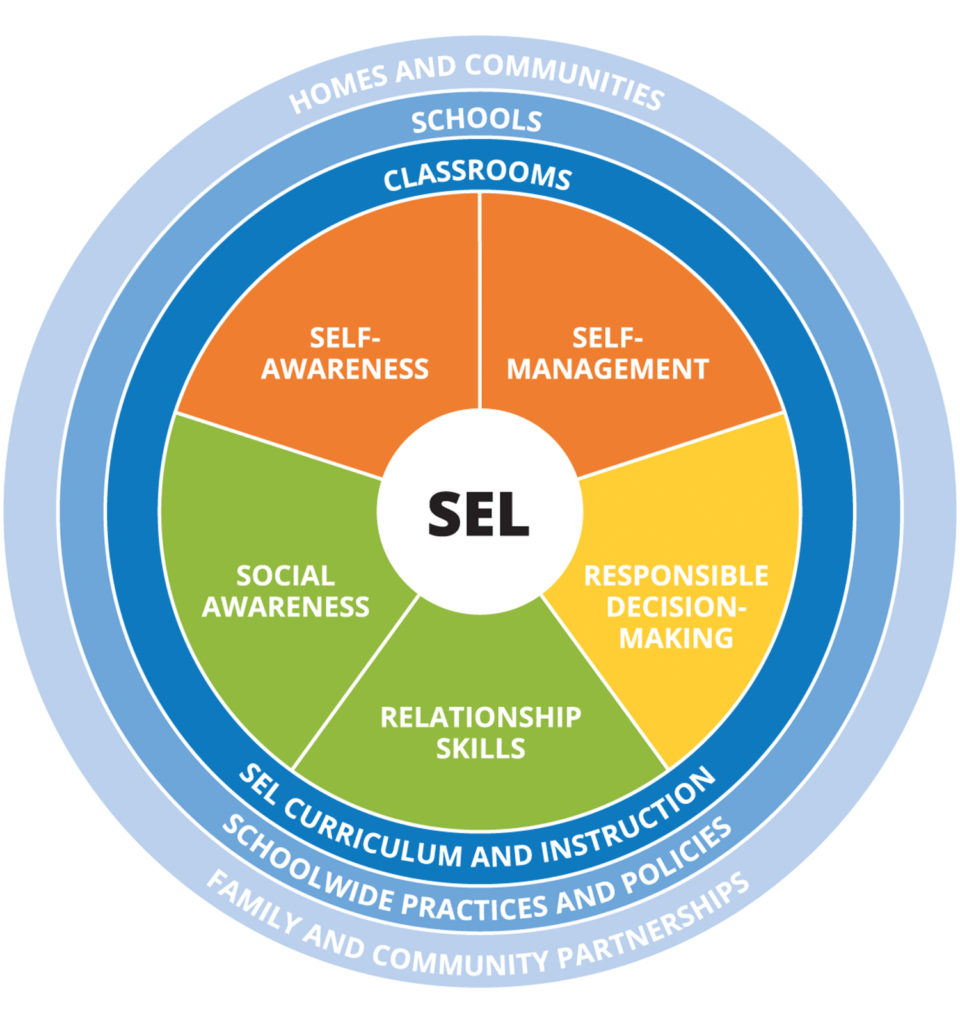

Social and Emotional Learning – Core Competencies

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) is one of the leading organizations promoting integrated academic, social and emotional learning for children in preschool through high school. CASEL’s framework of five core social and emotional competencies recognizes the skills, attitudes and behaviors that parents, educators and employers value. Students with these competencies do better in school, are more engaged, and are less likely to be involved in risky behaviors, as documented by a growing body of research.

Redefining Success

Last year, Punahou participated in a program called Challenge Success, run through the Graduate School of Education at Stanford University. Challenge Success has worked with over 130 schools across the country to live up to its name: challenging narrow, conventional definitions of educational success and broadening them to include the academic, social and emotional skills our children need to thrive in today’s world. The program’s vision statement reads:

“Challenge Success recognizes that our current fast-paced, high-pressure culture works against much of what we know about healthy child development and effective education. The overemphasis on grades, test scores, and rote answers has stressed out some kids and marginalized many more. We all want our kids to do well in school and to master certain skills and concepts, but our largely singular focus on academic achievement has resulted in a lack of attention to other components of a successful life – the ability to be independent, adaptable, ethical and engaged critical thinkers.”

Challenge Success helped Punahou to conduct an in-depth survey of its middle- and high-school students in the spring of 2016, and the findings revealed that Punahou students suffer from many of the same sources of distress as their peers in other high-performing independent schools across the country. In some areas, such as getting enough sleep for healthy brain and body function, the data was alarming. Other findings were reassuring – such as the fact that many students feel supported and “known” by one or more caring adult figures in the school.

Self-awareness

The ability to accurately recognize one’s own emotions, thoughts and values, and how they influence behavior. The ability to accurately assess one’s strengths and limitations, with a well-grounded sense of confidence, optimism and a growth mindset.

Academy Dean and College Counselor Erin Wilkerson ’89 Maretzki was part of the group from Punahou that attended Challenge Success’ annual conference in September. In her role, she sees that, “The pressures on these kids are just so stressful for them. Grades just came out and kids were in tears because they got Bs. And I’m trying to tell them a B is great. Grades make people so emotional. I want learning to make people emotional.”

Maretzki says she sees a fair amount of depression and feelings of low self-worth among her sophomores, in addition to stress, lack of sleep and “high levels of anxiety.” None of this is necessarily new, as feeling anxious and insecure are teenage rites of passage. But Punahou is not alone in seeing a greater demand for psychological, emotional and academic support in recent decades, mirroring the rise in “helicopter parenting” and the proliferation of programs and services aimed at grooming children for ever-increasing levels of academic achievement. Externally, the volatility of the 21st-century job market has made the pressure to be among the 3 percent of high-school students accepted into one of the country’s top 20 colleges and universities stronger than ever.

“Parents and kids get so hung up on the brand name and everyone’s just focused on college, college, college, when you really want kids to be able to do well in college and life,” says Maretzki. She and others point to a difference in generational experiences as one of the reasons family expectations may run counter to the latest research about healthy and enduring learning. “Most of our kids’ parents were raised at a time when college still was a pretty good indicator of what to expect afterwards, but I think in the last 20 years a lot of that has changed,” she observes. “What people don’t always realize is that we don’t even know what jobs are going to be invented by the time these kids are out in the world. That’s why we want them to pursue what they’re genuinely passionate about, because that’s where they’re going to see the biggest return. It’s critical for schools to get buy-in from parents though, they’re our most important partners.”

Social and Emotional Intelligence

If success is more than GPAs, test scores and name brand colleges, what does it look like? According to a growing number of educators, it needs to include social and emotional skills, bringing what were previously thought of as “soft skills” closer to the instructional core.

“Students need to feel safe and engaged,” says freshman Siya Kumar ’20, who also attended the Challenge Success conference. “We don’t want competition to get to a level that’s dangerous and we’re seeing that it’s slowly getting to that point. Our society has become so competitive, we’ve forgotten that we need balance. You can’t give yourself up to become successful.”

Self-management

The ability to successfully regulate one’s emotions, thoughts and behaviors in different situations – effectively managing stress, controlling impulses and motivating oneself. The ability to set and work toward personal and academic goals.

Kumar and her friend, Mei Lee ’19, agree that academic pressures increase as students approach college applications, and they quickly list off the various sources of this pressure: family, peers, one’s own desire to live up to “the perfect Punahou ideal.”

But as Lee points out, a lot of pressure is generated unnecessarily by simply not knowing how to discern between what’s relevant to you personally and what’s only “for show” on a college application. “Instead of always trying to please everybody, sometimes you’ve got to cut out some things,” she says. “Once you find your path, like the way you learn and what interests you, it can change your mindset about everything else. Education and life shouldn’t be based on what looks good on college apps, but what you find interesting. Because if you find it interesting, then it will help you decide what you want, and in the long run you’ll enjoy it so much more. You’ll be motivated because you love it.”

This is the kind of highly self-aware, intrinsically-motivated thinking that social and emotional learning is all about. It is also, unsurprisingly, one of the longstanding results of a Punahou education.

“Some of these social-emotional skills that we recognize now as being so important are part of what has set Punahou apart for a really long time,” says Academy Principal Emily McCarren. “We have put all this energy over the years into content-based knowledge, but in the meantime we’ve been having these amazing outcomes in our graduates because of our traditional focus on student-teacher relationships and our climate of care.

Social awareness

The ability to take the perspective of and empathize with others, including those from diverse backgrounds and cultures. The ability to understand social and ethical norms for behavior and to recognize family, school and community resources and supports.

“So all we’re trying to do now is identify and name these things that were happening by accident and ensuring that they have a purpose instructionally, and that every child has access to them. We want every student to be able to work and receive feedback on, for example, their ability to nurture strong relationships or their ability to self-regulate. We’re just demystifying those qualities that make Punahou alums valuable in whatever field they go into. We used to joke that it’s this Punahou magic but it’s actually these critical skills that come together in a self-aware, centered, self-motivated, passionate and compassionate person.”

Many graduates attest that it is these “soft skills,” like leadership, resilience, communication, empathy, and critical and creative thought, that lie at the heart of their education at Punahou and beyond. The challenge today is to create a rigorous system of defining, developing and assessing those skills, rather than leaving them up to chance. Because, as it turns out, 21st-century education is increasingly focused on these inter- and intrapersonal skills and applying them to real-world problems.

Junior School Principal Paris Priore-Kim ’76 adds: “We’re really unpacking the fundamentals of social-emotional learning and dissecting things like collaboration, communication, global understanding … because global understanding is not just diplomacy – it’s what lies at the core of being able to understand someone else’s perspective. In the same way that communicating well isn’t just that you feel fine standing up and speaking in front of people.”

Relationship Skills

The ability to establish and maintain healthy and rewarding relationships with diverse individuals and groups. The ability to communicate clearly, listen well, cooperate with others, resist inappropriate social pressure, negotiate conflict constructively, and seek and offer help when needed.

“We’re basically talking about the Aims of a Punahou Education,” says McCarren. “And if we as a community come to a shared definitionof all these things then we need to identify the competencies required to demonstrate these skills – for example, what does it look like when a student demonstrates the capacity for critical and creative thought?”

The process of educating parents, faculty and students about the value of social-emotional learning and eventually reimagining the high-school and middle-school curriculum is a long-term undertaking, says McCarren. “Even if we were to go at lightning-fast speed, we probably wouldn’t see significant changes until our current second-graders are ready to graduate,” she adds. “This is slow, complex work that requires all kinds of community education and engagement.”

The Academy’s G-Term was one way to begin exploring this work outside normal curricular frameworks. McCarren likens it to “a pilot of what curriculum and assessment might look like in the future. It’s also a way to have this conversation in a safe space where no one’s married to it and that allows us to experiment in a zone that’s not threatening.”

Measuring Success

While these conversations are still in their infancy, Punahou is not alone in considering alternative forms of assessment. The challenge is bridging this work with the world of higher education and creating a common language for evaluating whether a student is a good fit for a particular institution. Under McCarren and President Jim Scott’s ’70 leadership, Punahou is part of a national consortium of schools currently exploring a “mastery transcript” that could provide colleges with another way to measure a child’s skills and potential.

In a promising signal earlier this year, Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education released the report, “Turning the Tide: Inspiring Concern for Others and the Common Good through College Admissions.” Endorsed by 120 colleges and universities, it included recommendations for reshaping the college admissions process to reduce excessive achievement pressure, among other things.

“Many colleges and universities recognize that this admissions environment is unhealthy and that we need to attend to it for the sake of our students,” says Phil Ballinger, vice provost for undergraduate enrollment and admissions at University of Washington and a trustee of the College Board.

As one of the signatories to “Turning the Tide,” Ballinger is familiar with the challenges outlined in the report as well as the limitations in modifying college admissions processes. He points out that intentional dialogue between high schools and colleges is currently one of the most concrete ways to redefine parameters, and cites the example of Overlake School, which has a policy of limiting the number of AP courses its students can take. Because Overlake has such a strong reputation and a positive relationship with University of Washington, admissions officers don’t view the policy as a negative when students apply.

Responsible decision-making

The ability to make constructive choices about personal behavior and social interactions based on ethical standards, safety concerns and social norms. The realistic evaluation of consequences of various actions, and a consideration of the well-being of oneself and others.

“College admissions is a whole ecosystem in which colleges are really only half the equation,” says Ballinger. “If schools like Punahou were to take a leadership role, that could be an important part of moving this forward.”

McCarren stresses that this is not about making school less rigorous. “Children absolutely need to be challenged; they can’t learn if there’s no challenge. On the other hand, anxiety is not a necessary condition for learning and, in fact, we know from neurological research that it’s detrimental to learning.

“Our core aspiration is engagement, because engaged students worry less, cheat less, and they’re sad and angry less often. As we focus on student engagement, which is tied to all these social-emotional skills that kids need to learn in order to take care of themselves, we have to remember that we’re doing so because this improves learning environments. It’s not because we want to soften the learning outcomes or give everyone a trophy. We’re trying to figure out the optimal environment for student learning because a lot of the assumptions that school is built around are coming into question.”

“To me, academics are actually going to mean more,” says Priore-Kim. “Making these shifts is going to help produce more enduring, meaningful and applied learning, which is what all schools are being challenged to do. We understand so much more about what’s healthy for children and we are educating for a different future.”

In the words of Siya Kumar ’20: “We need to understand that our future is not defined by how well you do on a math test but who you are as a person and, when you get out of school, how you’re going to help the world around you.”

Do You Know?

These national statistics are selected from research assembled by Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education Challenge Success program.

- Over 17 million children in the U.S. under 18 have or have had a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, 32 percent of which are anxiety disorders. The median age at which a child is diagnosed with an anxiety disorder is 6 years old.

- Research indicates that 1 of every 4 adolescents will have an episode of major depression during high school.

- An online survey of 3,641 North American girls ages 8 – 12 demonstrated that while face-to-face communication was strongly correlated with positive social well-being, use of phone, online communication, video, music and other media were associated with negative social well-being.

- Children 5 — 12 years old need 10 — 11 hours of sleep per night. Middle school students need 9 — 11 hours and teens need 8 — 10 hours. There is an increasing demand on their time from school, friends and extracurricular activities as well as media and caffeine products — all of which can disrupt sleep.

- Students in grades 4 — 6 who went to bed an average of 30 — 40 minutes earlier improved in memory, motor speed, attention and other abilities associated with math and reading test scores.

- Eighty-five percent of adolescents are reported to be mildly sleep deprived, and 10 — 40 percent may be significantly sleep deprived. Sleep deprivation decreases motivation, concentration, attention and coherent reasoning; it also decreases memory, self-control and increases frequency of mistakes.

- Thirty-five percent of teens report that stress caused them to lie awake at night, and for teens who sleep fewer than 8 hours per school night, 42 percent say their stress level has increased over the past year.

- High-achieving private and public high school students average 3.07 hours of homework each night.

- Of 1,200 children ages 8 — 17 surveyed in a study by the American Psychological Association, 44 percent reported that doing well in school was a source of worry.

- While parental involvement may boost students’ confidence and abilities, over-parenting (helicopter parenting) appears to do the converse in creating a sense that one cannot accomplish things socially or in general on one’s own. Students who reported higher levels of over-parenting were more likely to endorse solutions that relied on others rather than taking responsibility oneself.

- In a survey of over 10,000 middle- and high-school students, 80 percent reported that their parents value personal happiness and achievement over caring for others. Youth were also 3 times more likely to agree than disagree with the statement: “My parents are prouder if I get good grades in my classes than if I’m a caring community member in class and school.”

- Nine- to 13-year-olds said they were more stressed by academics than any other stressor — even bullying or family problems.

- Seventy-three percent of high-school students listed academic stress as their number one reason for using drugs, yet only 7