Editor’s note: Fourth-grade faculty Kris Schwengel recently returned from a year-long sabbatical. While his proposed “auto query” is an unusual format for the Punahou Bulletin, we thought it was a fitting expression of Schwengel’s iconoclastic and innovative teaching style.

An Auto Query by Kris Schwengel

What is your definition of a Schwabbatical?

Great question! While the word sabbatical comes from the Latin word for “rest,” this opportunity and these research topics were too exciting to pass up. A Schwabbatical, in my experience, is a time to try new things, chase your professional and personal passions, and live each day like it’s your second-to-last. A sabbatical is essentially about time. Time to grow. Time to challenge your own assumptions. And time to dance.

What were the original goals of your sabbatical?

My Goal:

To help Punahou build bridges between the Junior School Learning Commons and the classrooms.

The Challenge:

As we change the hardware of our school, we must also initiate a software change. In other words, as we transform our physical campus, we should also be redesigning or at least reconfirming our educational programming.

What Success Looks Like:

A palpable symbiotic relationship between the Learning Commons and the surrounding classrooms, in which the Learning Commons facilities will support students as they collaborate on and create projects in the spirit of true 21st-century learning.

Why did you choose Mammoth Lakes, California, as base camp for your research?

I knew getting far away from Punahou would be essential to envisioning new paths for my work at the School – it can be hard to see the forest for the hala trees, so to speak. Despite its geographic isolation, Mammoth Lakes has a vibrant education scene ranging from progressive public schools to makerspaces to collaborative-communal workspaces to ski academies that turn learning on its ear.

What were your findings during your sabbatical?

I set out to answer essential questions that dealt with three aspects of 21st-century learning:

- Engagement of students with the material and each other;

- skill-building and project production versus content consumption;

- making learning fun and “sticky.”

Visiting the University of California, Los Angeles GameLab (a high- school summer camp for video game production) and Riot Games (an American video game developer and eSports tournament organizer whose online games are being played by 7 million people as you read this) reaffirmed my vision for students working in diverse groups while engaged in a meaningful and educational challenge. Imagine a coder, storyteller, musician, project manager and artist all working on a game simulation based on the American Revolution or the splitting of a cell.

The extended time away allowed me to sit down and draft a “MakerFesto” document, which is a blueprint for programming a makerspace from the rooter to the tooter. This 46-page manual is full of quotes from other educators from a survey sent out nationwide, project successes and failures. (See link at end of article to find the MakerFesto online.)

How can your findings support bridging the Learning Commons with the classroom studios?

Engaging with teachers around the world who are immersed in the Project-Based Learning model inspired me to explore how we can continue to transform learning on campus. First, we need to tackle the misconceptions about this type of learning, such as teachers abandoning instruction of basic skills. Any project worth its salt will require skills such as spelling, grammar, math and self-assessment. Investigating schools that have pivoted to PBL is both fascinating and daunting, because you cannot remain committed (or addicted) to content consumption and also present a strong PBL model.

This pivot is harder than it seems because we need to question and challenge how our own educations and careers have shaped our thinking about what true learning looks like. But it has become clear to me that if we focus on the needs of our current students, we cannot deny that they require new skill sets that are relevant to the rapidly changing and unpredictable world they are entering.

“Wide bridges” is a theory I developed regarding the two-way traffic between the Learning Commons and classroom studios. These metaphorical bridges support students as they journey to research and fabricate projects in the Learning Commons and then return to the classroom studio for the essential steps of presentation and self-reflection.

How did homeschooling your children for a year go?

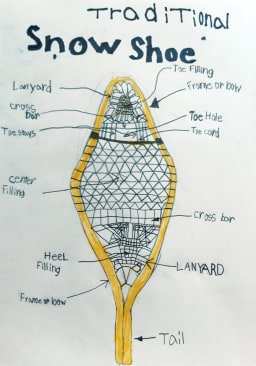

Leia ’25 and Woody ’27 thrived this year. We focused exclusively on inquiry projects and skill-building while shedding any concepts of scheduling and content consumption. One shining moment saw Leia creating the soundtrack (using GarageBand) for Woody’s coding game project based on skiing Mammoth Mountain. Collaboration, research-based decisions, skill-building and fun were all a part of their learning. If we were interested in snow shoeing, we did it. Following mouse tunnels under the snow? Did it. The workings of a BBQ? Done. Coding the random movements of snowflakes? Yup. We were also blessed to ski 156 days, enjoy two mountain bike seasons, learn to make pasta from scratch, hike to create a photo essay inspired by fall foliage and beaver dams, complete wood-burning art projects, and best of all: experience seasonal changes in ways that inspired our daily schedules.

What are your next steps on campus?

Punahou has taken amazing steps this past year to ensure students experience a 21st-century education, and I’m excited about the opportunities to continue engineering bridges between content and skills, makerspaces and classroom studios, and fun and learning. As for my part in this work, I hope to bring back some innovative ideas to ensure kids are engaged in sticky learning challenges and building skills they’ll really use in their futures. I’ll also be campaigning for the addition of Thousand Island dressing to the teachers’ dining hall.

What’s this I hear about a “Gratefulness Tour?”

Words can’t express my gratitude to Punahou for this experience. People were nothing short of stunned to hear a fourth-grade teacher could even take a sabbatical. It was never lost on me that sabbaticals are almost always reserved for college professors, and I plan on Mammoth black-bear-hugging each and every one of my 58 bosses on campus upon my return.