By Shannon Wianecki

Photo: Olivier Koning

Yunus Peer has taught History and World Civilizations at Punahou for the past 26 years. And for almost just as long, he’s juggled a second full-time job: contributing to revolutionizing STEM education in rural South Africa.

From 1954 to 1994 the Bantu Education Act deprived South African youth in majority Black areas from receiving math and science training. Peer explains: “The Bantu Education Act decreed that Black children didn’t need math and science beyond elementary grade level because their future was going to be manual labor. So, no Black child could ever dream of being a doctor, scientist, mathematician or astronomer.” The cruelty of this policy still disturbs him. “For all the brutality of apartheid, nothing was as brutal as the Bantu Education Act. It destroyed the life dreams of millions of children.”

In 2001, Peer took it upon himself to address this long-standing injustice. “Punahou has such an amazing faculty, I wanted to take my colleagues to South Africa to help teachers in rural schools there. And rather than tell those teachers what to do, I wanted them to send us their list of priorities.” This simple plan evolved into Teachers Across Borders South Africa (TABSA), a grassroots volunteer organization that has equipped thousands of rural educators with the tools they need to inspire students in STEM fields. More than 200 U.S. teachers, 30 of whom were Punahou faculty and alumni, have accompanied Peer on this critical mission – resulting in the mentoring of 7,500 Southern African educators who have touched the lives of millions of students in rural areas. “I am indebted to past Punahou President Jim Scott ’70 and Director of Instruction Diane Anderson for approving the pilot program in 2001,” he says. “To send Punahou teachers to a country on the opposite side of the planet that had just gone through a political and social revolution took a great deal of courage and confidence.”

workshops in STEM subjects to educators in rural South Africa – closing the educational divide that lingers after the end of apartheid in 1994.

Peer is uniquely suited to run this far-reaching project. He was born in Port Shepstone, a South African town close to the exact opposite side of the globe from Hawai‘i. “Maybe my destiny is to bring two sides of the planet together,” he laughs. Furthermore, Peer doesn’t just teach history; he lived it. The grandson of migrant laborers from India, his birth certificate is checked “Free” which Peer described as “a relative term” under the racist policies of apartheid. His father Cassim Peer never had the opportunity to attend school, a handicap that didn’t prevent him from building schools in Black villages. Peer remembers that as a child in the 1960s, his father told him that Nelson Mandela would be president of South Africa one day.

Cassim sent his children out of the country for school. “He didn’t want me growing up thinking I was a second-class citizen, that I wasn’t worthy of anything,” says Peer, who attended Waterford Kamhlaba in Swaziland (now Eswatini). His classmates included the children of imprisoned political leaders Mandela, Sisulu and Bishop Tutu.

“I am indebted to past Punahou President Jim Scott ’70 and Director of Instruction Diane Anderson for approving the pilot program in 2001, to send Punahou teachers to a country on the opposite side of the planet that had just gone through a political and social revolution took a great deal of courage and confidence.”

— Yunus Peer

To punish Cassim, the South African government confiscated Peer’s passport, effectively holding the teen under country arrest and preventing him from finishing at Waterford school. It took Cassim three years to retrieve his son’s passport – and when he did, 19-year-old Peer left for India, traveled across Asia to London, New Jersey, and ultimately to Hawai‘i. The University of Hawai‘i offered him resident tuition under a reciprocity agreement.

“As an international student I had to be extremely resourceful and creative. To pay my rent I would buy cars off insurance lots, fix and sell them. I went to class during the day and worked as a janitor at the University at night.” The hustle paid off; Peer obtained degrees in both psychology and education. He applied for political asylum and married a girl from Kailua just in the nick of time. Two weeks later, his deportation papers arrived in the mail. His marital status allowed him to stay.

He taught at Maryknoll High School from 1980 to 1985, then moved to Andover, New Hampshire to teach at Proctor Academy. In 1994, he obtained a master’s degree in public administration from the University of New Hampshire in Durham after three years of night school. To address the crisis in his home country, Peer spent many hours touring schools in New England, explaining to people that the U.S. support of the South African government was wrong. “The U.S. agreed with the apartheid government that Mandela was a communist and a terrorist. He was not,” says Peer.

Finally, in a stunning reversal, South African leaders dismantled apartheid. Mandela walked free, and ran for president in 1994. “My dad was so excited because he voted for the first time in his life at age 69.” Mandela visited Peer’s hometown to express his gratitude to his supporters. Peer’s mother remembered him as “a wonderful, warm old man who made everyone feel comfortable around him.” He complimented her on the Indian roti she made, a rare treat he savored with Ahmed Kathrada, his Indian cellmate of 26 years on Robben Island.

Cassim Peer passed away in 1997 before he could vote for Mandela a second time. Peer’s mother didn’t wait a day before asking her son, “Now what are you going to do?’’ He had hefty shoes to fill. Serendipitously, South Africa’s new Minister of Education expressed a need for mentors in math and science to make up for the void left by the Bantu Education Act. In the years after apartheid, Black children in cities were able to close the gap with their White classmates, while children in under-resourced rural schools remained far behind. “We needed to find a way to help the government reach teachers and students in the rural areas.”

Peer approached Punahou with his plan, supported by assurances from his family and friends in South Africa. The School agreed to send teachers; his mom agreed to house, feed and transport them in South Africa. The pilot team consisted of three Punahou math teachers, Mike Pavich, Jim Clarke and Mike Vogel, with Steve Hanks from Honoka‘a High School on Hawai‘i Island. One hundred South African educators attended three workshops in two provinces in the first year.

Twenty-two years later, it remains a labor of love. Each December Peer starts planning the teacher workshops from scratch. He clocks in at 8 p.m. Hawai‘i time, to communicate with his colleagues since South Africa is 12 hours ahead. They discuss by email the most critical curricular needs in math, science and now, robotics. He asks the Department of Education for their priority topics in those subjects. Then they figure out the logistics of where to host 300 to 500 teachers over three weeks in June and July.

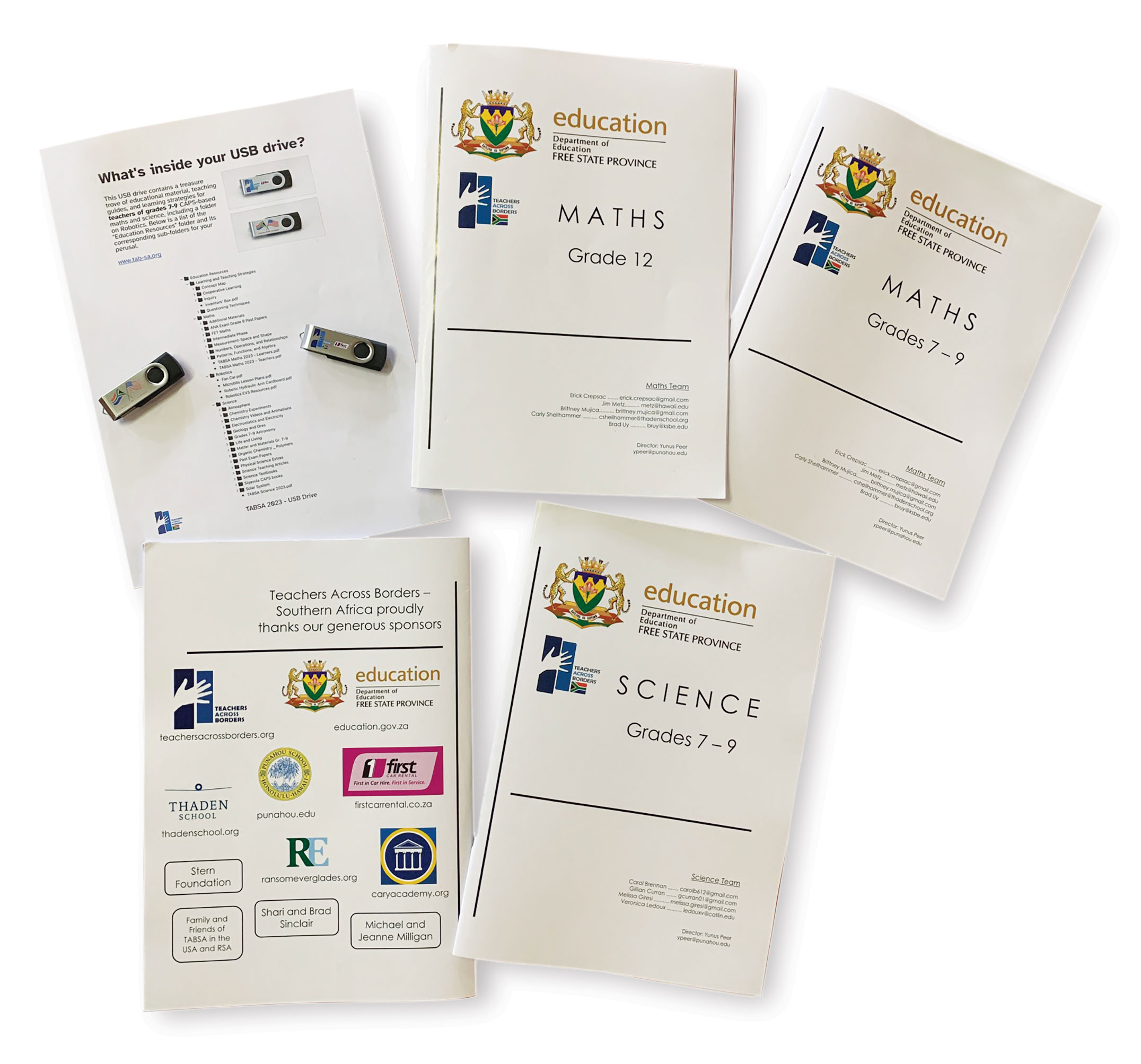

Peer then recruits a team of 10 – 15 educators from various schools across the country who agree to pay their own airfare and prepare lessons in their discipline under the South African Department of Education guidelines. The lessons must accommodate large classes with little or no access to lab equipment and must use everyday, readily available materials. TABSA’s volunteer coordinator, his daughter, Nadia Peer, collates these lessons into workshop booklets and flash drives.

In June, Peer and his wife Laurie Lee ’80 travel to South Africa ahead of the team to secure lodging, food and transportation and to confirm all the arrangements made through the year. The day after the volunteer teachers arrive, the TABSA team piles into three vans sponsored by First Car Rental, and they set off for their assigned province. Over the next three weeks they log 14 – 16-hour days, sharing, teaching and learning with an average of 200 attendees per week.

“We have five or six classes going simultaneously with 30 – 40 per classroom,” says Peer. The South African teachers are dedicated to becoming better teachers; they’ve sacrificed their winter break to attend the workshops. “Our U.S. teachers look at their subject in a whole new light, and most say they learn more than they teach! The workshops require the cooperation and contributions of a vast network of people in two countries and the process of putting it together and then seeing the magic take place in the classroom is the greatest reward for me,” he says. “It means our children can dream of careers without boundaries determined by the color of their skin.”

The experience proves profound for both attendees and volunteers. Early on Peer coaxed Punahou’s Jim Clarke into joining the team. “He was this brilliant math teacher and a curmudgeon,” says Peer. “But when he returned, he could not talk about South Africa without becoming sentimental.” When he died in 2016, he left TABSA $5,000 in his will. Peer created a teacher scholarship in Jim Clarke’s name in Eswatini (Swaziland). He was not around to see it, but a young man graduated from college and became a math teacher through Jim’s generosity.

Aside from teacher development, Peer runs a few side programs. In addition to fully equipped computer labs, TABSA provides student scholarships, school uniforms and sanitary pads to rural communities. The TABSA Uniform Project was developed by Jay Seidenstein, retired Punahou history teacher. In 2023 TABSA commemorated Nelson Mandela Day by dedicating a coding and robotics lab for a 1,200-student school in the Free State province. To avoid shipping costs, the team transported 30 laptops in their luggage. In all, TABSA has donated more than 300 computers for 10 labs in rural schools, and even one computer lab to a Pretoria prison for incarcerated youth.

“We needed to find a way to help the government reach teachers and students in the rural areas.”

— Yunus Peer

TABSA produces this educational bonanza for roughly $50,000 each year with donations from friends, family, churches and schools. The South African government shares the cost of the workshops in-country. After wrapping up the TABSA program, Peer returns home to prepare for his classes at Punahou. “I am so excited about returning to the classroom after watching math and science teachers working together in South Africa.”

It’s a Herculean effort, to be sure, and now that he’s entering his 46th year of teaching, he’s ready to hand over the reins, “preferably to a U.S. institution with resources willing to provide the best personal and professional development for U.S. teachers and help our colleagues in South Africa who were never given the opportunities we have in the First World.”

The progress continues in June 2024 as plans are already in place for workshops in South Africa with 600 teachers of math, science and robotics. “The South African government estimates that this program has directly benefited 2 million students but that’s only a drop in a very large bucket,” says Peer. “We have 20 million more students to reach.”

As he prepares for TABSA’s 21st year, Peer acknowledges the need to pass the torch to an institution with resources to continue this international professional development program – and to impact the remaining 20 million more students in South Africa that TABSA has not reached. Left, Brad Uy ’99, teacher at Kamehameha Schools, Kapa-lama and current math captain of TABSA.

Right: The South African government estimates that TABSA has touched the lives of more than two million students. This sign sits in the courtyard of Tsoseletso High School, (Bloemfontein, Free State Province) where the 2023 workshops were held.