Mark Noguchi ’93 has sprung to action amid the COVID-19 crisis to do as he long done – to help those in need in the local community. With Hawai‘i’s restaurants closing their dining rooms, thousands of pounds of food has been shuttled to Aloha Harvest, which collects and redistributes food to Hawai’iʻs hungry. Pili Group, headed by Noguchi and his wife, Amanda Corby, cultivated a partnership with Pacific Gateway Center, acting as the hub of food distribution.

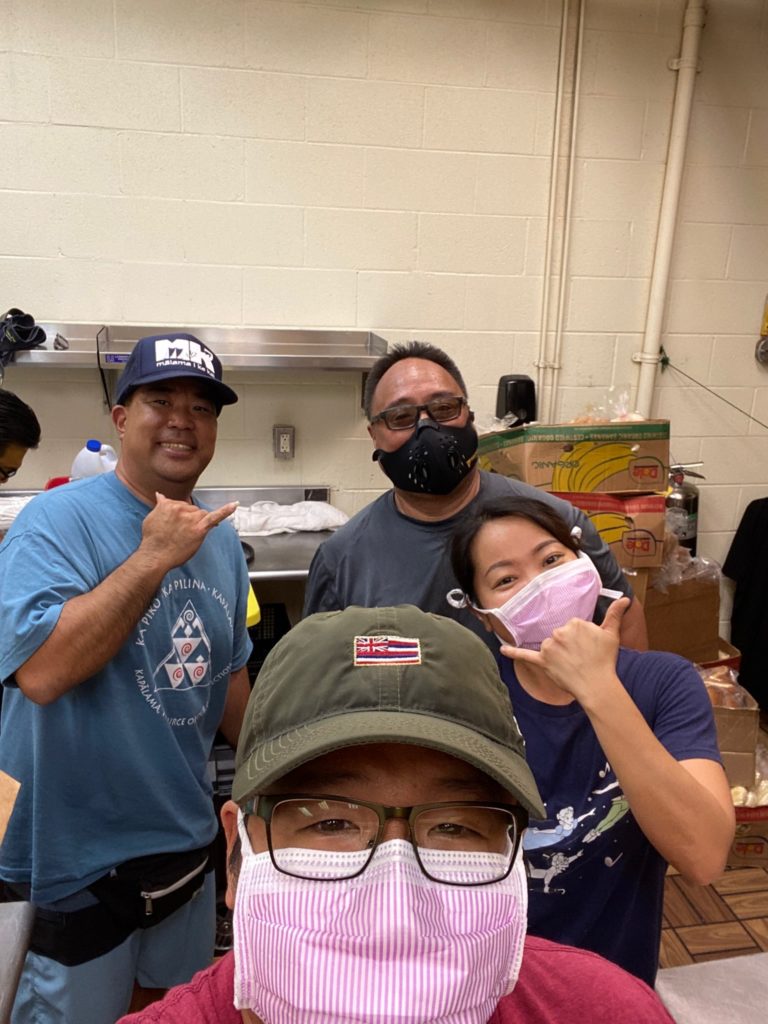

They partnered with chefs and restauranteurs looking to support the community, and created a website, chefhui.com, to build a network around the effort. “Our team breaks down the donations into manageable-sized deliveries to other organizations already cooking,” said Noguchi, a notable chef and Punahou’s food curriculum specialist. “Amanda on the back end, has stayed in touch with Hawai‘i Food Bank, Waianae Comprehensive, Lili‘uokalani Trust, etc. to ensure that we’re all working towards the same goals, and we have the least amount of outreach overlap as possible.”

About half of the group’s daily drops go to the University of Hawai‘i West O‘ahu, where close to 5,000 kupuna meals are prepared each day. The remainder head to Makaha communities, Salvation Army and groups cooking along Ko‘olaupoko and Ko‘olauloa. Although restaurants remain limited to take-out and deliveries, Noguchi says he’s seeing a decrease in restaurant donations, which means that the group will soon need to buy products for the deliveries. While he and Corby are working with various organizations and investors to secure funding, he welcomes outreach from ranchers, farm owners and others in the food industry who may want to sell products at a discount or donate. He also is looking for kitchens to prepare meals for communities in need.

For more information about the effort, visit chefhui.com or email chefhuihi@gmail.com.

While on-the-go on Thursday, Punahou’s Team Up podcast editor Allen Murabayashi caught up with Noguchi and interviewed him for this podcast (see podcast player above), where he talks about the struggles those in the restaurant industry are facing, his current efforts to distribute food, his work at Punahou and his sources of inspiration.

You can find Punahou’s Team Up podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Simplecast and Google Play.

Podcast Transcript

AM: Thanks for joining our Team Up podcast produced by Punahou School. I’m Allen Murabayashi, an alumnus from the class of 1990. As part of our #PunsUnited coverage of the COVID-19 outbreak, we’re interviewing alumni working on the front lines of this global health crisis. They’re out in force playing instrumental roles and helping their communities across the world during this unprecedented time.

Mark Gooch Noguchi, class of 1993, made his name in the restaurant community as a champion of locally sourced foods and worked at Chef Mavro and Ed Kenney’s Town restaurant. He branched out, opening a series of restaurants before starting the Pili Group, a catering and events company. After giving a talk to students for Punahou’s entrepreneurial accelerator program, Academy Principal Dr. Emily McCarren approached him with a job offer, to join the faculty, but continue to work with the community. Mark’s life work is a manifestation of the idea of Punahou as a private institution with a public purpose.

You’re Punahou’s food curriculum specialist, but most people know you as a prominent chef in the community. Can you quickly give a background of your culinary experience?

MN: Well, I’m very proud that this year made 20 years in my industry. When Punahou asked me to come aboard, I think I feel very blessed because Punahou still allowed our company, Pili Group, to thrive. They could have said, ‘We’d like you to come aboard, and all you can do is Punahou.’ But in discussions with Punahou, I think a good deal of the community outreach that helps to facilitate the activities that we do at Punahou, it helps that I’m still involved in my restaurant community. So, there’s this balance of developing curriculum and still supporting my colleagues outside of the Punahou campus, which is what we’re doing right now.

AM: Obviously, here in Hawai‘i, we are confronted with the outbreak of COVID-19, as is the rest of the world. I went over to Fete restaurant in downtown Chinatown the other week, and I saw Chuck Bussler, who is one of the owners of Fete with his wife, Robynne Mai‘i. He told me that what we’re seeing is ‘An extinction level event.’ Can you talk about what you’re seeing in the restaurant industry in Hawai‘i?

MN: Yeah, I think to many listeners, what Chuck said may sound extreme, but if you can imagine people like Chuck, Ed Kenney and the Le family, and I can name all of our small restaurant family and groups that we have here, all of a sudden, in less than a week, every single person in our initiative has been confronted with the reality that they might not open doors when this is through.

And I can’t orate the feeling that you are responsible for the livelihood of how many other people, and my colleagues have had to tell their employees, ‘I’m really sorry we need to let you go for the sake of survival.’ And even after letting everybody go, the employees in how many restaurants I’ve seen, the employees get laid off and they show up for work the next day. It shows a couple of things. One, it shows a dedication to our craft, a dedication to our industry, but our dedication to our leaders. And that’s huge.

AM: What doesn’t the public realize about all the people that are involved in the supply chain supporting local restaurants?

MN: I think it is very hard for the general public to understand how small the margins are for the hospitality restaurant service industry to thrive on. People see our friends with beautiful places, accolades out the door, magazine covers, awards, and they think, ‘Wow, they’re killing it.’ Even when we had our restaurants, that’s what people would say. ‘You guys are killing it.’ And we might be busy, but it every restaurant, what was it, 40 percent closed in the first three years. If you make it past five years, you’ve beaten the majority. So, it takes five years before we get to a point where you can start building if you’re lucky on that stick.

AM: You’re still very involved in the community. You’re even driving around all morning doing deliveries. Can you tell me what you’re up to to support the community right now?

MN: The evening that we heard the news and realized that our education systems were going to be shut down and put on extended leave, I think that evening I was talking with my wife, ‘I wonder how our public school kids are going to eat.’ Almost one in five children go to school hungry. And there’s a lot of our keiki that depend on that public school lunch. That’s their only full meal of the day. That’s the truth.

And we’ve done a lot for the Kokua Foundation, and Jack and Kim responded back the next morning saying that, ‘Great, we had already gotten a few emails.’ And so, bunch of us started putting our heads together. And then, we got on a call with state and city and county, and they were not yet ready to activate. But community groups had already started activating on their own.

So, what we figured was why don’t we leverage our network and our community and start to help those guys that are cooking already. Allen, you as a community leader yourself, you know how when there’s a big project, everybody needs something from you, and even though we feel obligate to try and satisfy all those needs at one time, sometimes the best use of our time is to stay put and start connecting the dots? That’s what we did.

And we were able to partner with Aloha Harvest, who is the state’s largest, I guess, food rescue company. They have this incredible network of restaurants and outlets that we’ll call them at the end of the day when they have extra food. They’ll pick it up and then they distributed to different shelters around Oahu. We partner with them. Pacific Gateway Sandwich is a kitchen incubator. And we started to intake all the food and ingredients from restaurants and hotels that were closing their doors or are really paring down. And then, from there, we take a pallet of eggs and break it down into four deliveries or five deliveries for groups that are cooking already.

This morning, all the driving around is because the trucks, right now, are busy. There’s a couple of different loads that I’m just helping out with. They need to be picked up. So, that’s why communities are activating at this grassroots level. And even, I had gotten a call from someone asking, ‘Hey, how can we as a state move quicker?’ And I was like, ‘You’ve got to trust your community.’ They’re doing it. They know how to do it. Hakipu‘u and Ko‘olaupoko – they have been feeding their community through crises for years. We need to trust our community. They’re already doing it.

AM: There are obviously a lot of people who are working from home, a lot of people seeing the news and trying to figure out how can they help. How can the Punahou community help in this effort right now?

MN: Ways that people can help in the Punahou community is we have a community from every sector in Hawai‘i – health, medical, ranching, restaurant, et cetera, you name it, law. We formed a little website called chefhui.com, where we’re putting up information, things that groups, community organizations around need, but also a place where people can email us if they have a concern or if they want to reach out. I think that one thing that’s important to tell our Punahou community is that this is a marathon. It’s not a sprint. So, we are getting a lot of wonderful people that are saying, ‘How can we activate now?’ And we’re saying, ‘Okay, well, send us an email, give us your contact and as these needs continue to grow and build, we’ll reach out to you.’ But I think it’s very important for us as a community to know that this is not going to be done in a couple of weeks.

AM: Yeah. Some people have suggested go to your favorite restaurants and buy gift certificates even if you might not be able to cash it in later, because it helps these restaurants just stay in business for a little bit longer. Is that something in the short term that we can do to support local restaurants?

MN: I think that’s one thing – that’s a great idea. I would also say for those of us in our respective fields, like the health industry. If you are in the medical field, and you know that supplies are needed, I would say throw it up there. If you are a member of your community, that’s how you can activate and people will hear that. There are people that are more empathetic to the needs of our health workers in restaurants. That’s fine, that’s great. Support that way. I think that simply by the act of checking in our neighbors…

One thing that we’re forgetting about our kupuna besides just feeding them is they are probably used to being around family and friend and their other kupuna, their other peers. So, we’re missing that human interaction, is being missed. Dr Paris Priore-Kim’s husband started this kupuna delivery service, and we were talking about last night. And I think one of the greatest gifts that he is providing is he is providing a human interaction.

As a community, guys, go scream at and call at your neighbor. Just ask your neighbor how you’re doing. It’s that sense because we’re trying to still cultivate and hold sacred the honor of community even though we’re isolated. And I think that if all of us did that, the impact that it would have on our social, emotional wellbeing would be immediately noticeable. I do believe that. I know it might sound a little cheesy. ‘Oh, you’ve just got to love your neighbor.’ No, but for real, more time ever than now to aloha the people around us is huge.

AM: When I talk to kids about you and your career, I often point to you as a guy who… Fair to characterize you as not the best student in high school?

MN: Yep, totally. I own that.

AM: I like the fact that you found a way to find your own path, and it didn’t necessarily have to be in high school, where a lot of kids nowadays feel so much pressure to define who they are. Can you talk a little bit about at what point you found yourself, found what you were interested in?

MN: I’m still finding myself I think, but I definitely have a greater amount of focus and direction. If I have found myself, perhaps it is that I do believe that my place in life is one to be of service. That is definitely something that has been a common thread in everything that I’ve done. But I feel like in today’s day and age, with media and technology, everybody is expected to produce and be authentic and be the best human that they can be, that hashtag, being your best self, everyone is expected to be that.

And when you’re young, and you are still trying to find the core of who you are, our youth, especially our high schoolers, are at this cusp where they’re about to break off and step into that intermediary point of being on our own, because most of us at that age aren’t on our own. We still have a scholarship for college or family helps us. So, there’s this incredible amount of pressure to be somebody.

And I think it’s really important to slow down. And it’s definitely something that I tell students when I interact with them, is don’t feel that you have to know exactly what you’re doing, exactly where you’re going. And perhaps that goes against what some parents say. So, if I’m contradicting what you’re telling your children, I apologize. But I’ve been asked to share me and my story and my path and create a curriculum with that. So, this is the experience that I know and how I got here.

AM: When you were a rising chef on the food and beverage scene here in Honolulu and the rest of Hawai‘i, you were a very early adopter of sourcing ingredients locally, which now sounds somewhat obvious with the whole farm-to-table movement. But why were you such an early champion of this cause?

MN: I feel that a lot of it has to do with my time with Halau o Kekuhi. My time with halau and hula gave me definition on things that I felt inside of myself. I was always drawn outside. I was always drawn to our home. But I definitely did not know how to parlay that into a profession. Hula started to give some definition where we learn the stories of where we came from. We learn the stories of the plants and the animals and the clouds and the rain around us. So, that starts to clarify this love.

And then, in traveling around the world with hula, started to understand that food brings us together in ways that are sometimes obvious, as in if it’s your grandmother makes this amazing dish year after year. But it also translated to ways that are not so obvious. In other words, learning how to have respect in how we pick la‘au for lei translated into this respect and reverence for the food that we grow here. And I didn’t realize that until later.

AM: We’ve got to step back just a second because you’re downplaying it. For the audience who’s not in the hula world, can you explain what Halau o Kekuhi is and who Nalani Kanaka‘ole is?

MN: Okay, I’ll try to do my best and I’m going to try not to sound stuck up. Halau o Kekuhi is a small hula group out of Hilo, Hawai‘i. It has been multigenerational and it’s a matriarchal where the women have held the knowledge. And so, the chants and the stories in the hula have not been diluted by subject to interpretation. We are a Pele halau that is the source of our energy and our knowledge and our inspiration. Our style of dance is known to be ‘aiha‘a or low to the ground. It’s very intense. It almost looks rough. When you watch halau dance, there’s a different energy and we’re not subtle.

AM: The halau actually flew up to New York a couple of years ago to perform at The Joyce Theater, which is a very well known dance theater. And I hosted them for dinner at my apartment and they had two dozen people doing hula in my New York apartment. It was unbelievable.

MN: Isn’t that cool?

AM: Yeah, so great.