By Catherine Black ’94

How can Punahou build a learning experience that ensures the pioneering mindsets and skills needed to address the challenges of a changing world? The K – 12 Learning Commons are two facilities – one in the Junior School and one in the Academy – that represent the School’s vision for the future of education.

Most parents would do anything to ensure their child’s future success and happiness. For many, this includes providing the best education possible, often with great personal and financial effort. But with the professional landscape changing so rapidly in the new millennium, precise definitions of a top-tier education can seem elusive. When reviewing the research on education and job readiness over the past decade or so, the numbers are telling.

- Public school performance standards and testing outcomes are slipping, despite major government initiatives like “No Child Left Behind” and “Common Core State Standards.” 1

- Between 1980 and 2012, the age at which young workers reach the median wage has increased from 26 to 30. 2

- Forty-five percent of recent college graduates return home to live with their parents. 3

- Sixty-five percent of today’s grade-school children will end up in jobs that haven’t been invented yet. 3

- Just 11 percent of employers – yet 96 percent of academic provosts – believe colleges are effective in preparing graduates for the workplace. 3

- The cost of private school education nationwide is rising faster than the rate of inflation. 4

- Forty-seven percent of current U.S. jobs are at risk of automation within the next 20 years. 5

- Young college graduates are heavily represented in jobs that require only a high school diploma or less. 6

- More than half of recent college graduates are either unemployed or underemployed. 6

- The cost of higher education has risen faster than median family income, requiring many students to take out expensive loans that mortgage their futures. 7

While some of these numbers are still being debated in the aftermath of the Great Recession, the general trend is clear: In order to prepare children for a rapidly changing workforce and global economy, many fundamental assumptions about how education is designed and delivered must change. The irony is that, unlike industries that must respond quickly to market demands in order to survive, education is slow to shift course. This has caused its relevance to be questioned by growing numbers of analysts, employers and successful entrepreneurs who contend that a college degree does not necessarily guarantee the appropriate skills one needs to make it in the world today.

What are these skills? There are numerous variations on this theme (including the Aims of a Punahou Education), but best-selling author, education reformer and Harvard School of Graduate Education Thinker-in-Residence Tony Wagner summarizes essential 21st-century survival skills as follows:

- Critical thinking and problem-solving

- Agility and adaptability

- Effective oral and written communication

- Collaboration across networks and leading by influence

- Initiative and entrepreneurship

- Ability to access and analyze information

- Curiosity and imagination

These aptitudes, which Wagner articulated after interviewing hundreds of business, nonprofit, philanthropic and education leaders, describe someone who can innovate and create value in today’s world; someone who knows how to ask the right questions, sees opportunity where others see challenge, and thrives on the uncertain edge that spurs creativity and invention. This would be the opposite of someone who is groomed to follow instructions and be a predictable gear in a highly structured labor force – in other words, the industrial-era skills that our modern educational system was designed for more than a century ago.

During a visit to Punahou this past January, Wagner pointed out that there are depressingly few schools intentionally building a curriculum to develop today’s essential skills. Despite growing evidence to the contrary, most educators still reward individual achievement over collaboration; abstract specialization over real-world multidisciplinary approaches; passive content absorption over creative problem-solving; fear of failure over learning through trial and error; and extrinsic over intrinsic motivation.

The world no longer cares how much Punahou graduates know. What the world cares about is what they can do with what they know.

Students traditionally studied content to become “college ready” and curricula were designed to facilitate ranking for college placement. But “we no longer live in a knowledge economy – most of the routine knowledge work is being done today by computers. The world no longer cares how much Punahou graduates know,” Wagner said. “What the world cares about is what they can do with what they know, because we are now living in the era of innovation and we see the immediate implications of this in the world of work.”

Wagner shared the example of Google, which analyzed its human resources data and found no correlation between job performance and an employee’s GPA, SAT scores, or college pedigree. “Google used to only hire kids from Ivy League schools with the highest GPAs and test scores. Right now, 15 percent of new Google hires do not have a B.A. degree. They no longer ask for a transcript because the transcript only tells them about seat time served in college. It does not tell them about the skills they need to succeed at Google.”

Innovators and Entrepreneurs

Erik Jia ’18 and Bobby Liu ’19 met on the bus going home from school and discovered they shared a mutual passion: devising solutions to problems they noticed in the world around them. As a young boy, Liu acquired a taste for self-education, reading articles voraciously on the internet, hanging out in Barnes & Noble, and closely following inspirational organizations like Humanity+ and Mindvalley Academy, and individuals like Elon Musk. Today, Liu spends three hours a day on average (sometimes more on weekends) on his personal learning outside school and schoolwork.

Jia has been interested in business and entrepreneurship since he was a freshman and, like Liu, feels there are infinite opportunities to address widespread needs in society (he is particularly interested in problems associated with student health and well-being). This past spring, the two decided to collaborate on a venture and, after analyzing a number of options, zeroed in on the lower back pain that they and many of their peers suffer as a result of lugging around heavy backpacks all day. Their research uncovered a few specially designed but costly backpacks that addressed this need, but no simpler, cheaper devices that could be connected to a bag the way lumbar support cushions can be added to office chairs and car seats.

After school and on weekends, the two began an exhaustive process of research and development to create a cushion that could counteract the habitual deformation of the spine when carrying a conventional backpack. They cold-called a chiropractor’s office to request an informational meeting, which helped them understand the mechanics of back health. They bought a cheap computer program to help them design their product and made dozens of trips to Walmart and Home Depot, testing a variety of materials – from foam rollers to pool noodles – in a series of prototypes that they assembled by hand at Jia’s apartment.

When the chiropractor responded enthusiastically to one of these models, they took to the streets for market research, asking 76 random individuals at Ala Moana Center between the ages of 15 and 25 to test their product and give them feedback: 9 out of 10 gave it a thumbs up. They visited the Small Business Development Center, filed for a General Excise Tax License and began the process of securing a patent. When they realized they had done all they could to build homemade samples of their device, they called a local prototyping and product design company to inquire about next steps for mass production. The owner agreed to meet with them on a Saturday.

“It was really depressing,” remembers Jia. “He told us that just the mold for the elliptical shape in our blueprint would cost around $25,000 and the casing would be about 15 times what it cost us to make using supplies from Walmart. But it was incredibly helpful because we understood the industry a lot more and he basically showed us reality. We were too optimistic, thinking that for a couple hundred dollars we could start production. So we went back to the drawing board.”

Searching for a way to make more professional samples of their product, the friends decided to see if there were any resources at Punahou. Liu remembered the woodshop in Case Middle School and dropped in one day. Design and engineering faculty Taryn Loveman and Aaron Dengler listened to Liu’s idea and immediately offered to help. They showed him how a laser cutter and CNC (computer numerically controlled) mill could be easily programmed to cut the elliptical cushion they had been previously cutting by hand, and suddenly the project was moving forward again. Now, the two are preparing their latest prototype for a Kickstarter campaign to generate support and seed money for an initial manufacturing run.

There are many notable elements to Jia and Liu’s story, but one of the most interesting is that the two didn’t turn to Punahou as a resource until quite late. When asked why, their answers reveal a perception of school as a place to do “schoolwork” more than to carry out an entrepreneurial initiative. In some ways, it was sheer luck – Liu’s memory of his middle-school shop class – that led them to the human and technical resources that they needed.

Liu thoroughly enjoys school, calling it “a learning environment where you get to experience new ideas and be surrounded by students who are hungry for bigger things.” He believes that all his classes have something useful to impart, as long as he focuses on what’s applicable to his life in a broader way. Yet when asked what portion of his overall education he attributes to Punahou, his response is ambivalent: “I would say certain skills like writing and math. But most of the stuff I learn is on my own … self-education for me is a bigger thing.”

Jia expresses a similar sentiment: “I feel like at Punahou, when you look for opportunity, you find it. If I ask for support, nobody’s going to say ‘no.’ They always say ‘yes, go for it’ and they’ll provide me with all the resources they can.” But after a pause, he adds, “I do find it to be more lacking in terms of entrepreneurial opportunities. [This project] has been like school outside of school, I’m learning so much from it.”

“We can’t afford to let brilliant students like these find an outlet for their passion by chance, which is why the K – 12 Learning Commons becomes so critical,” says Academy Principal Emily McCarren. “Faculty and academic leadership are working to design a learning environment that intentionally connects students with their interests and gives them all the necessary resources to pursue their questions, projects and dreams.”

How is Punahou Changing?

At the dawn of the new millennium, education was challenged by the young field of neuroscience and a more sophisticated understanding of the brain that contradicted long-held assumptions about how people learn best. Coupled with the radical new rules of the “innovation economy,” this changing landscape has urged Punahou to explore new approaches to pedagogy, faculty professional development and campus design – sometimes at a speed that feels dizzying when compared with the pace of change over the preceding century.

“Because we know more and more about how learning works, and because technology has transformed how we think about education, we recognize that a traditional school system is not sufficient for creating those realities for every child,” says McCarren. “The true value of an education is measured over a person’s lifetime and we have to create environments where children can see connections between things, where they can tackle real-world challenges, where they can ask the questions that they truly wonder about, and where their wonder can drive how they learn.”

Junior School Principal Paris Priore-Kim ’76 notes: “We risk operating in a paradigm that trains children to enter a world that no longer exists – that’s the urgency.”

The good news is that many of the elements built into the DNA of a Punahou education are as relevant today as they were 100 years ago: breadth and depth of opportunity, attentiveness to the whole child, a climate of care and community, and high expectations for students, faculty and others, to name a few. Punahou students continue to distinguish themselves across all fields – a testament to an environment that encourages children to do what many education reformers advocate: feed their curiosity, explore their personal interests, and develop an authentic sense of purpose that will shape their journey through Punahou and through life.

But despite its deep humanistic roots and child-centered philosophy, Punahou – like all other schools of its age and prestige – shares the same foundations as the rest of our traditional educational system. This is prompting a healthy process of questioning the established practices of education, such as the value of grades and test scores in measuring a student’s learning, or organizing curricula by separate disciplines.

Punahou has always approached change through a thoughtful, reflective process of testing and refining new instructional methods with the feedback of students, faculty and families. The past few years have seen a number of such explorations – with the Mastery Transcript Consortium and G-Term examining new approaches to student assessment and the realignment of several K – 12 programs (such as global education, social responsibility and entrepreneurship, Hawaiian Studies and sustainability) to more fully integrate school priorities into every child’s experience.

Perhaps the most ambitious of these initiatives is the K – 12 Learning Commons, which faculty have been conceiving for more than six years. Initially prompted by the opportunity to reimagine school libraries, the vision for the K – 12 Learning Commons has expanded to become a template for the type of educational experience both teachers and students can expect at Punahou in the years to come.

What is the K – 12 Learning Commons?

When completed, the K – 12 Learning Commons will consist of two spaces – one in the Junior School’s Sidney and Minnie Kosasa Community and one in the Academy’s current Cooke Library – that function as a hub for the creative and collaborative energies on campus and form an integral part of every student’s Punahou journey.

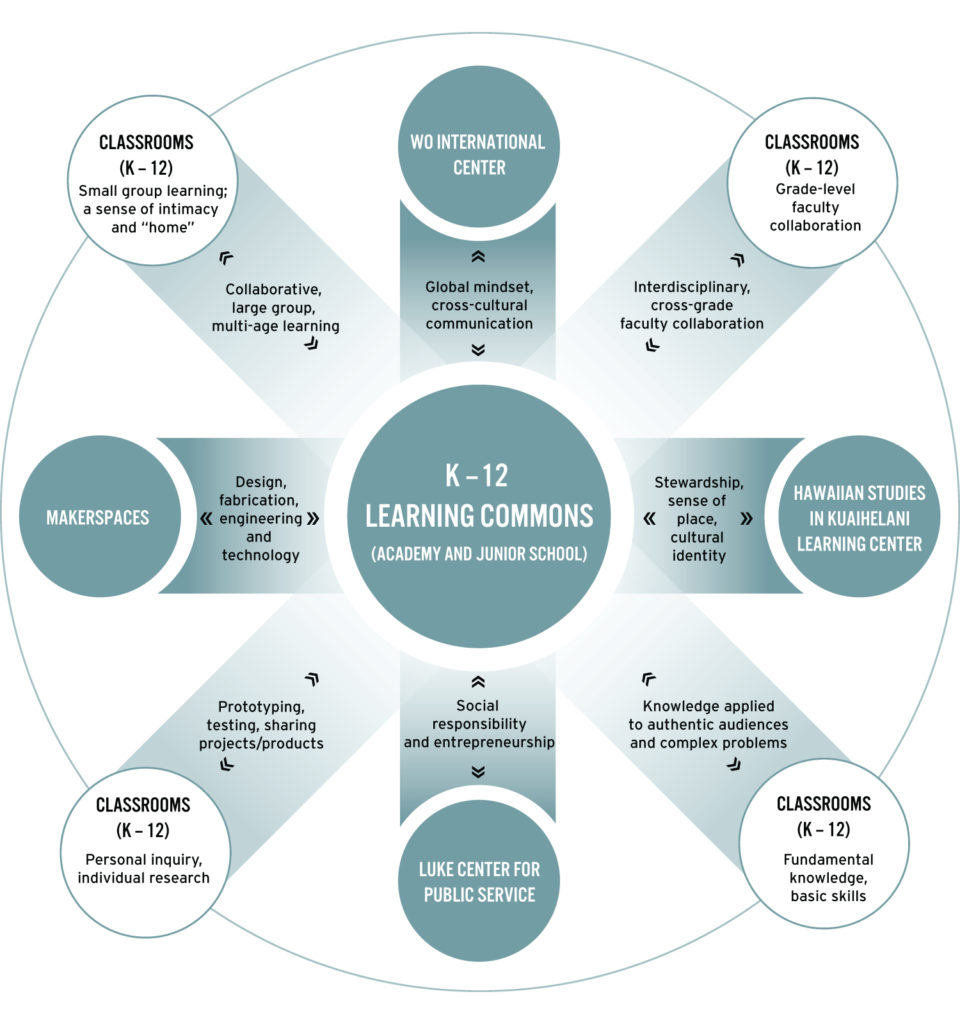

While the two facilities are located in different areas of campus, they will work together and in tandem with the School’s other creative learning centers – including Wo International Center, Luke Center for Public Service, Kuaihelani Center for Hawaiian Studies – to deploy a fully networked array of resources so that students like Erik Jia ’18 and Bobby Liu ’19 can bring their personal inquiry projects to life.

Fundraising has been underway since 2013 for the Junior School Learning Commons, which is a central element of the emerging Kosasa Community. While the architectural transformation of Cooke Library into the Academy Learning Commons is still in the planning stage, faculty schoolwide have been building on the successes of other flexible and unprogrammed spaces (the Gates Family Science Workshop in Mamiya Science Center and Creative Learning Centers in Case Middle School and Omidyar K – 1 Neighborhood) and experimenting for several years to define the student experience the two Learning Commons facilities will provide.

For example, last year, Junior School teachers piloted an “Imagineering” course for all students in grades 2, 3 and 5, testing out curriculum in hands-on technology and the “makerspace” concept (makerspaces or makeries are collaborative spaces for people to invent and build projects using a range of tools). Concurrently, Academy engineering faculty were prototyping for the new D. Kenneth Richardson ’48 Learning Lab, scheduled to open in January in the Mamiya Science Center, where it will function as a sophisticated design and fabrication space with the type of high-tech equipment one would find in a professional production workshop. Cooke Library has undergone a number of experiments in its internal spaces in the last two years, adding areas like a video makery, an “unfinished theater,” a peer-to-peer learning center, a café, a restorative studio for activities like meditation and yoga, and an exhibit space. A number of professional development opportunities have helped faculty incorporate hands-on, applied learning projects into their teaching, and Summer School courses such as “Art, Design and Fabrication” have enabled teachers to test out new curricula and tools for different age groups.

A recently formed department, Design Thinking, Makery, Engineering and Technology (D-MET), convenes K – 12 faculty working with educational technology, engineering, fabrication and design. The D-MET department’s instructional philosophy is grounded in the design-thinking process, which encourages students to identify an authentic problem and audience, and go through the iterative steps of designing a solution through trial, error and improvement based on real feedback. While it’s easy for people to associate this process primarily with fields like engineering and technology, faculty are quick to clarify that it can apply to intangible ideas such as social services or systems such as patient care delivery in a hospital.

“The goal isn’t the object,” says D-MET faculty Taryn Loveman. “The goal is empowering a mindset and a series of skills so students feel they can have an impact on the world. It doesn’t have to be about building a product, it can be about social entrepreneurship or creating experiences as well.” If anything, Loveman adds, the social and emotional component to creative problem-solving is perhaps most important of all, because it urges children to work together and develop empathy for others. “That’s what employers in today’s job market want; they’re a lot less interested in whether you have memorized a specific piece of information than if you can work with a team to solve a problem.”

The K – 12 Learning Commons will be at the center of a campus-wide network, connecting Punahou’s classrooms and program-specific centers to the School’s broader instructional vision.

In the K – 12 Learning Commons, students will:

- Build congruency between their experiences in school and the real world;

- Have the appropriate spaces and resources (technological, creative and human) to transform their questions into meaningful work that addresses authentic challenges and audiences;

- Make connections with students and teachers from different classes, grades and disciplines to spark collaboration and innovation;

- Learn from outside experts and mentors whose knowledge and networks can broaden their thinking about relevant, real-world questions.

In the K – 12 Learning Commons, faculty will:

- Have a shared space that facilitates interactions and connections across grade levels and disciplines, helping Punahou truly leverage its potential as a K – 12 institution;

- Belong to a thriving professional community with resources and programs that help them to deepen their learning and share it with one another;

- Work with partners from Hawai‘i and beyond to explore essential questions and new approaches to education that can be shared within Punahou and across the community.

School as Community

The Learning Commons will offer a multiplicity of spaces with different functions: quiet areas for study and research; fabrication studios for inventing, prototyping and building; visual and performing art spaces; media labs for creative production; meeting rooms, social café-like spaces and exhibit areas for sharing one’s work. This atmosphere will be much more similar to the dynamic work environments that companies like Google or Apple have built to stimulate creativity and innovation than the self-contained classrooms and department-specific buildings traditionally associated with school campuses.

“All that variety supports personalized learning so that students’ interests and passions are ignited,” says Priore-Kim. “The Learning Commons becomes a transparent space for collision and for unlikely partnerships, a place that gathers people not just from our community but from beyond campus as well.”

“We want to create relevance and congruence between the world outside of schools and what students experience in schools,” says McCarren. “But we don’t currently have spaces that allow us to do this. We’ve been chipping away in pilots and prototypes, trying out ideas in basements or existing multipurpose rooms, but we can’t achieve our goals until we have the spaces that are designed specifically for them, which is what makes the Learning Commons so critical.”

Those goals include bringing people together by creating a place that draws in the School’s diverse, talented community and facilitates meaningful collaboration and purposeful, student-driven learning. They point to a holistic educational experience that draws on Punahou’s mission to create the conditions for children to realize their full potential as contributing members of a global human family.

“One of the most important things that school can offer today is community,” says McCarren. “These big spaces that we’re calling the Learning Commons become a demonstration of the many incredible pathways that children and adults can take to a deeper understanding of themselves and the world around them. That’s something you can’t learn on YouTube or experience through social media: a family of caring adults who accompany children on their personal journeys of self-discovery, and that’s the promise we need to fulfill to every one of our students.”

An inside look at the future Junior School Learning Commons in the Kosasa Community

Stepping Stones to the K – 12 Learning Commons

1841

Punahou School is founded as a self-sustaining farm school where boarders must contribute to the institution’s livelihood, including farming, building, sewing, repairs, etc.

1910

The study of manual training and domestic arts is formally incorporated into Punahou’s curriculum.

1921

J.B. Castle School of Manual Arts opens, producing an impressive list of student-led projects: the original Alexander Field bleachers; furniture and a solar water heater (the largest in the world at that time) for Wilcox Hall; Dillingham Hall’s switchboard (the most advanced in the territory at the time of its construction) and its 45-by-62-foot cyclorama; a 30-car garage; a campus telephone system; the first hydroplane ever constructed in the Islands; and a glider aircraft. The glider made a 35-minute flight and won the first glider pilot’s license issued in the Territory of Hawai‘i, signed by Orville Wright.

1925

The Punahou Farm School opens in Kaimuki, offering male boarders an agricultural training program and helping to provide food for the main campus in Manoa (the school closed in 1929 for financial reasons).

1929

Manual arts curriculum is instituted for middle-school students.

1961

A more modern shop is created in the basement of Castle Hall.

1979

Castle School of Manual Arts closes to make way for the Hemmeter Fieldhouse and Athletic Complex.

1999

Mamiya Science Center opens, with the Gates Family Science Workshop serving as a multipurpose, hands-on learning space for students K – 12.

2001

One-to-one laptop program instituted for grades 4 – 12.

2005

Case Middle School is completed, with three learning centers dedicated to multipurpose, hands-on student experiences, including the Charles and June Gates Learning Center which is now home to the robotics and engineering studio.

2011

K – 12 faculty brainstorming begins to imagine the future of the School’s library spaces, giving rise to the concept of a K – 12 Learning Commons.

2012

Faculty are broadly introduced to the design-thinking process and encouraged to incorporate it into lessons and institutional problem-solving, including the development of new campus facilities that reflect instructional vision.

2014

Planning gets underway for a redesign of the interior of the Gates Family Science Workshop to create an innovative engineering and design facility, thanks to a gift from former Hughes Aircraft president, Ken Richardson ’48.

2015

Prototyping for a variety of makerspaces begins in Castle Hall, Gates Family Science Workshop (Mamiya), Gates Learning Center (CMS), Cooke Library and Bishop Learning Center, among others.

2016

The first phase of the Sidney and Minnie Kosasa Community for Grades 2 – 5 opens, with studio classrooms designed around many of the same principles of transparency, flexibility and collaboration that will shape the design of the Junior School Learning Commons. Faculty introduce an Imagineering course to students in grades 2, 3 and 5.