As part of a pilot underway at Punahou, grades are all but gone in a handful of Academy classrooms, replaced by a mastery-based model of assessment, in which students get robust, frequent feedback of their progress based on skill sets.

By Mary Vorsino

In an Academy chemistry class, students huddle around laptops, creating videos to explain chemical processes at work. How does a raincoat repel water? Why does water boil at 95 degrees Celsius in Denver? How does a water droplet make a rainbow?

The talk centers on chemistry, how to explain concepts and creating videos that are engaging and clear. What isn’t being discussed is how they will be graded. In fact, the only time grades are mentioned is in reference to how they’ve largely disappeared.

That’s a fundamental shift – and one that Punahou and other schools across the country are carefully exploring to prepare students for college and beyond.

Technology has completely transformed education – how teachers teach, what students learn and what skills colleges and employers want to see in leading applicants. But grades have doggedly remained – a vestige of the Industrial Age – reducing a student’s progress, strengths and accomplishments to a single letter (and GPA on a transcript).

That’s become a significant limitation, one that presidents at leading college campuses and hundreds of top college preparatory schools across the country, including Punahou, say must change to ensure students can thrive in a world that values mastery of skills, initiative to apply those skills, and persistence over testing prowess and memorization.

The problem, many say, is not only that grades are inflated or oversimplify a student’s high school experience. Grades too often dictate how courses are designed and overemphasize successful completion or marking the right bubble, instead of truly learning skills.

“In education, very little has changed in how students are assessed, but it needs to change quite urgently,” Academy Principal Emily McCarren said, adding that the traditional high school transcript isn’t just less useful. It’s now getting in the way of students’ success.

That’s why, as part of a pilot underway at Punahou, grades are all but gone in a handful of Academy classrooms, replaced by a mastery-based model of assessment, in which students get robust, frequent feedback of their progress based on skill sets. In these pilot classes, teachers determine what skills are important, how students can learn them and how to assess the acquisition of these skills.

The initiative is part of a larger effort at Punahou and hundreds of other schools across the country to evolve our system of teaching, learning and assessment. Part of what has made this possible is the concept of a mastery transcript.

A mastery transcript, which includes digital links to student videos, reports and other presentations, is designed to articulate a student’s strengths and competency in key skills without using grades. But educators emphasize that it’s much less about re-thinking the high school transcript than allowing for innovation in the classroom.

“Assessment has profound importance – what’s measured gets done,” said Claremont McKenna College President Hiram E. Chodosh. “Thus, focusing on how we measure, why we do so and how to improve it is vital. A mastery transcript holds the promise of telling us what a student has learned, from the basic knowledge, literacies and numeracies to the higher-performance capabilities.”

Top Schools in Country Exploring Mastery Transcript

The Latin School of Chicago, San Francisco University High School, the Buckley School in Southern California and the Spence School in New York are among other leading U.S. independent schools piloting a mastery-based model.

The movement comes as hundreds of the nation’s top colleges are fundamentally changing how they evaluate applicants, including de-emphasizing the SAT or making it optional altogether. Employers likewise are making it clear that today’s students must be ready to think critically and creatively in the workplace.

Mastery transcript is not Punahou’s end goal, McCarren said, but the inevitable byproduct of fundamental changes in skill sets required by colleges and employers. Today, critical thinking is more important than encyclopedic knowledge, and working collaboratively is more valuable than memorizing a formula, she said.

Punahou’s newly formed Mastery Learning Team is now working with teachers and administrators to incorporate new models of teaching and design new types of transdisciplinary courses that meet graduation requirements, the first of which will debut in the 2019 – 2020 school year.

Among the new team-taught courses that have been approved: A class that delves into a deep examination of how bias is experienced in American history; one that focuses on issues of global sustainability; and another on Polynesian voyaging demonstrated by building a Punahou canoe.

Punahou Joins Mastery Transcript Consortium

In 2017, Punahou became a founding member of the Mastery Transcript Consortium, an organization composed of 225 U.S. schools that have partnered with top-ranked universities to develop a new digital mastery transcript, which won’t give colleges a cumulative GPA or be organized by courses. It still, however, will be readable by a college admissions office in two minutes or less, and it will differentiate a student’s performance across a series of mastery credits, from content areas (like STEM and the humanities) to skills, such as self-directed learning. A prototype is now being designed and will be available to schools as early as summer 2019.

Traditional transcripts, however, aren’t likely to go away any time soon, considering many colleges still require them. But different types of transcripts may be delivered to different schools, depending on the assessment criteria.

Instead of focusing on the transcript itself, however, the emphasis should be on “unleashing innovative teaching and learning and really being able to allow faculty and schools to innovate in a more significant way,” said Mark Milliron, co-founder of the education tech corporation, Civitas Learning, a former administrator at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and an advisor of the Mastery Transcript Consortium.

“This isn’t just a crazy idea from independent schools and from some innovators,” he added. “This is part of a much broader movement. The big foundations in the education world and the U.S. Department of Education are all investing in competency-based education.”

Punahou English teacher Michelle Skinner is piloting the mastery model in her ninth-grade courses, assessing students not just on subject knowledge, but on critical and creative thinking, listening and speaking, engagement and collaboration. The focus is on progress.

“A mastery framework allows for failure and setbacks that lead to learning,” she said. “Everything a student does for a course can lead to learning. But in the traditional system, we assign some sort of points to all those things. That can lead to a student being marked down for legitimate struggles with new information, whether or not the student learns and grows in the end. With mastery learning, we acknowledge and give space for those struggles.”

Students in Skinner’s classes also evaluate their own work, so they become more in charge of their own learning. In a recent class, while analyzing Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” she divided her ninth-graders into small groups and had them consider what “collaborating effectively” means. From there, students are asked to assess their own progress throughout the course, considering Skinner’s feedback.

Despite the promise of mastery learning, the transition won’t be simple or easily accepted by students and their parents. For years, Skinner said, students have been taught to track their grades. “We’re replacing grades with something more complex,” she added.

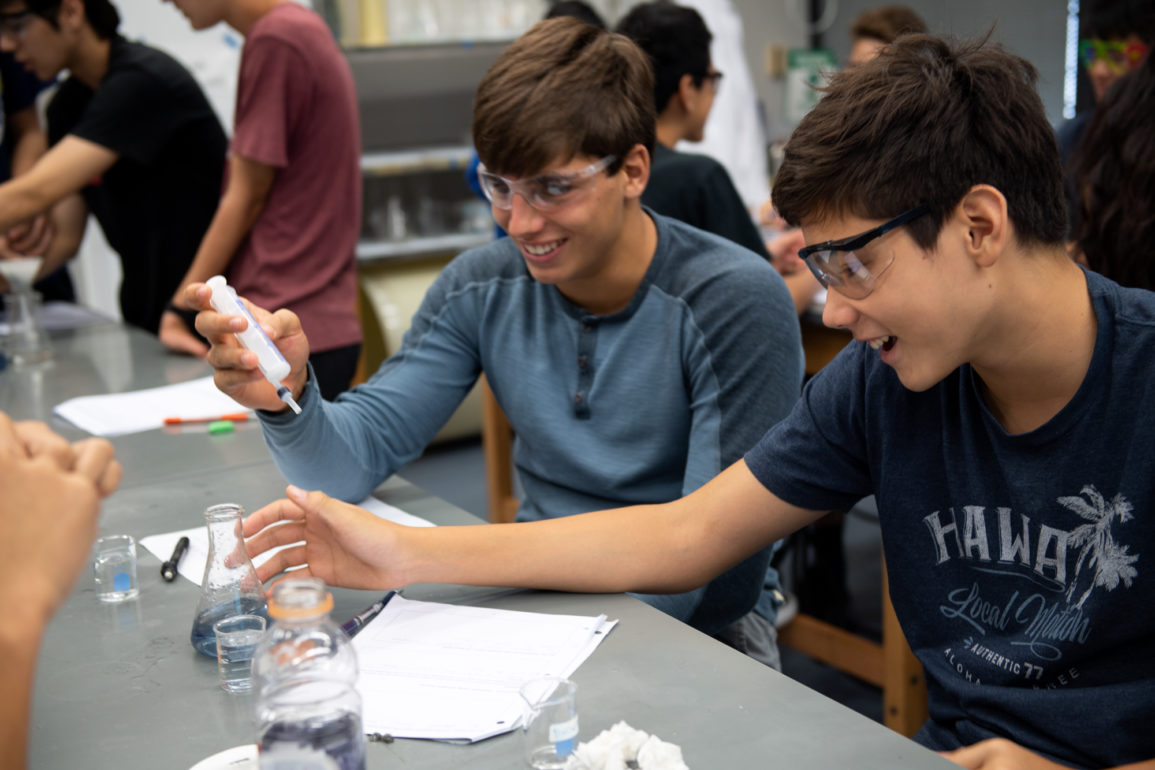

Academy science teacher Darcy Iams, who is piloting mastery-based learning in her chemistry class, said students need to be assured they won’t be penalized while figuring out how to meet new kinds of expectations.

Punahou’s faculty chemistry team identified 13 competencies for which to assess students. These include things like understanding the molecular scale, but also being a clear communicator and being persistent, which are important skills for scientists.

“It was a big change for everyone,” said Kacie Shimizu ’21, who is in Iams’ chemistry class. But, she added, once students immerse themselves in assignments, they’re not thinking about grades.

While mastery-based learning at Punahou is still in its infancy, members of the School’s Mastery Learning Team are working to acclimate faculty, parents and students to the new concepts.

“We’re helping people to understand the why,” said Sally Mingarelli, Punahou Academy assistant principal and teacher, who is helping oversee the chemistry pilot. “Our next step will be helping people to understand the how. And from there, we’ll be prepared to build a when. We’re not starting from the when. This is a movement in the build-up phase.”

But taking a proactive stance is vital considering the increasing number of colleges who are on board.

Stacy Caldwell, CEO of the Mastery Transcript Consortium, believes colleges will start getting a flood of schools using mastery transcripts within eight years. A number of elite colleges, including Harvard, Dartmouth and MIT, have already said they won’t disadvantage students who have “competency-based” transcripts.

As such, “Punahou is committed to making sure we continue to provide a cutting-edge education,” McCarren said. Mastery-focused assessment “represents a shared belief in our kids’ potential.”

Additional photo caption:

Top: Veronica Heen ’22 and Braydon Simmons ’22 recite lines in an English class taught by Michelle Skinner, who is piloting a mastery model in her ninth-grade courses.

More Stories on Mastery Learning

Colleges Driving Changes

Why Consider Mastery Learning?

President’s Desk: A Focus on Mastery