By Catherine Black ’94

On May 17, 2018, Punahou’s Board of Trustees announced the School’s next president: Dr. Michael Latham ’86, currently the vice president for academic affairs and dean of Grinnell College. He will become Punahou’s 17th president on July 1, 2019, following Jim Scott’s ’70 retirement.

On a November morning in 1985, on a rain-soaked hotel golf course in Lihu‘e, Kaua‘i, Mike Latham finished fourth overall at the state cross country meet, in the fastest time of his senior season. More important to him, however, was his team’s victory and the quiet satisfaction that they had won the state title together. Years of training, some marred by injury and illness, had led to that moment. As far back as when he was 12 years old, his sister Jules Latham ’87 recalls, Mike would roll out of bed before dawn on many a Sunday morning and run in solitude out of Haha‘ione Valley, across the streets of Hawai‘i Kai, often as far as Kāhala.

By the time he departed for college, Mike had completed the Honolulu Marathon three times. Running had become a significant part of his life, and it may be an appropriate metaphor for his intense commitment to the things that matter to him.

“Long distance runners are the kind of people whose incentive comes from within,” says social studies faculty Michael Georgi, who coached Mike in cross country and track at Punahou. “They’re not looking for glory, they’re incredibly dedicated and disciplined, and they tend to thrive on self-reflection and introspection.”

A Promising Start

Mike was 6 years old when the Lathams moved to Hawai‘i. His mother, Nancy, worked in the Hawai‘i State Department of Education for decades as a school counselor, curriculum specialist and principal. His father, Peter, was a career Navy officer and his grandfather had served as captain of a submarine during World War II, later commanding the submarine base at Pearl Harbor and marrying a Kaua‘i girl, finally settling on O‘ahu.

Mike and sister Jules grew up with this extended family, which included several Punahou graduates, and both entered the School in seventh grade. For Mike, it was the perfect environment to channel his extraordinary work ethic and unleash his intellectual curiosity. As Jules puts it: “Punahou gave him an outlet – it was a place where he could just put his head down and go.”

It didn’t take long for his peers and teachers to realize how intellectually gifted Mike was. “When asked to name my best student in 37 years at Punahou, I’ve never hesitated to name Mike,” says retired social studies faculty Jay Seidenstein. “What most impressed me were his almost unbelievably intelligent contributions to class discussions – he seemed to speak in carefully proofread paragraphs. His classmates and I were often awed by his responses, and yet he was careful not to intimidate them.”

Mike was in Seidenstein’s first AP U.S. History class, which involved four difficult multiple-choice tests per semester. Because it was his first year teaching the course, Seidenstein decided to take the tests himself to measure his own understanding of the material: “I did pretty well, but Mike outscored me on just about all of them. Every teacher has had students who they realize will soon know more about the subjects they teach than they themselves do – this was one of those cases.”

Mike would have excelled academically by dint of hard work alone, but he was truly motivated from within. “He’s just one of those high-octane thinkers who loves learning,” says Wren Wescoatt, a Kamehameha Schools graduate who competed with Mike in cross country and eventually became a close friend. Toward the end of their senior year, while most students were just trying to survive exams and get to graduation, Wescoatt remembers that he and Mike took an AP English exam on the same day. “Mike called me afterwards, eager to talk about one of the poems in the exam … I mean, who does that?” he laughs.

Mike credits his teachers with introducing him to the thrill of learning: “Every class in Jay Seidenstein’s course was built around an interpretive question or an open-ended problem. Whether we were discussing the origins of the American Revolution or the legacy of the Civil Rights movement, each problem Jay put on the table had these moral and ethical threads that inevitably led to questions of value or meaning. And that’s where history got really exciting for me, because it wasn’t just names, facts and dates anymore. You had to wrestle with the implications of your own thinking: What’s your perspective on this issue? And more importantly, why does that matter? What difference does it make? The fact that Punahou teachers always encouraged these kinds of questions was tremendously exciting for me.”

After graduating from Pomona College (one semester early, summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa), Mike went on to pursue a master’s degree and doctorate in history at the University of California, Los Angeles. It was at this time that he met his wife, Jennifer, a Russian literature graduate student at University of Southern California and an avid runner herself. She quickly realized that Mike wasn’t like other guys she’d dated. Of course he was brilliant, she says, but also incredibly kind. While walking the streets of L.A., the two would often buy a meal for someone in need. “You don’t see that in a lot of 26- or 27-year-olds – a way of looking at the world where there is a real sense of empathy and responsibility for others,” she says.

Mike’s compassion and sensitivity are remembered by many of his high-school peers as well. “I really looked up to him,” says classmate and friend Ken May ’86. Both ran cross country and track, and even though May was the top runner on their state championship team, he says that Mike was his inspiration. “Mike led by example; just being around him made you want to be a better person.”

Jamie Lui ’86 shared a number of classes with Mike and was part of the same group of friends that ran cross country and track. “As accomplished as he was academically and athletically, he never sought to be in the limelight,” she says. “He was patient and humble, always willing to help and genuinely happy for other people’s successes.”

Mike says he learned how to face the world with integrity and empathy from his parents. “I really am the son of two public servants,” he reflects. “That was what both my parents were about – this deep commitment to some cause beyond yourself. And a sense that this was your obligation, that you had been given a number of advantages and therefore had a responsibility to think about how your work would serve a larger purpose. There are a lot of ways you can measure a successful career, but I think for them, it was whether you’re doing what you can to improve the lives of other people in a tangible way.”

Punahou’s sense of place, its grounding in Hawai‘i’s culture, tradition and history, is a force for distinctive excellence and a major part of what distinguishes it from other schools.

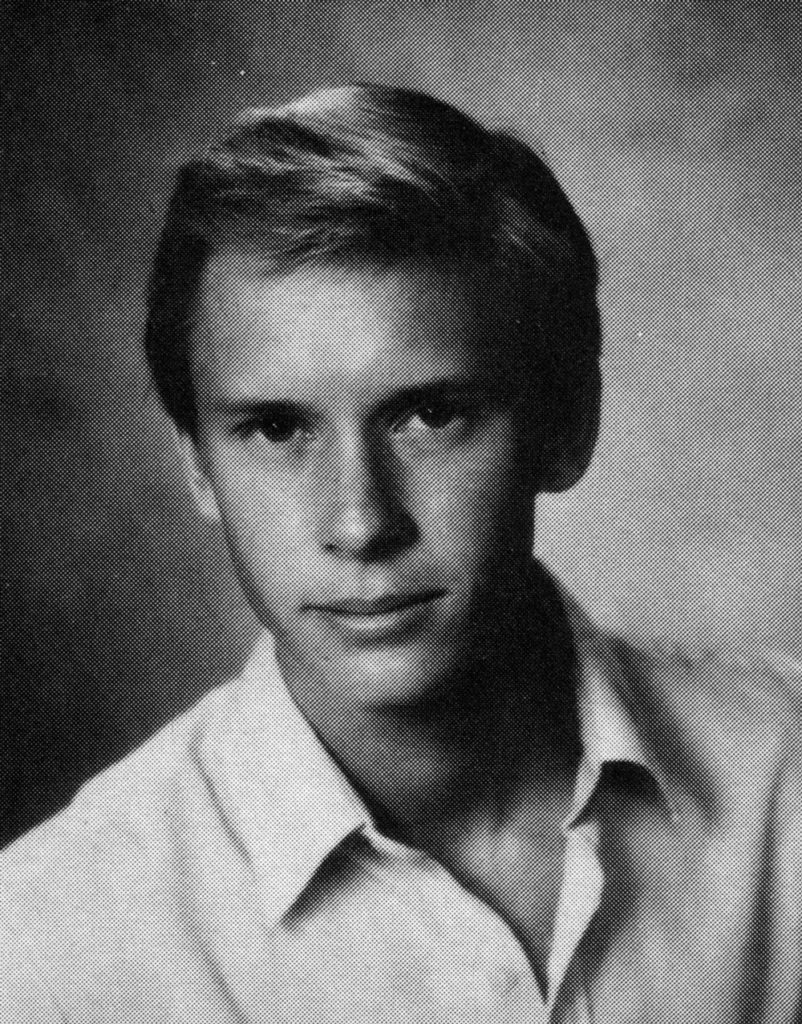

President-elect Mike Latham ’86

Finding His Stride

After college, Mike nevertheless wrestled with the tension between his interest in academia and the uncertainties of a career in it. “There was a moment where I was doing some really serious thinking about which path I was going to take. A part of me was drawn to a professional trajectory that was more predictable and financially secure, one that would remove a lot of the anxiety that emerges when you’re considering a Ph.D. in American history,” he says.

He spent some time working as a paralegal at a corporate law firm in San Francisco and realized that his vocation lay elsewhere. “I liked my colleagues and I loved San Francisco, but I didn’t have the same passion for the work. Teaching a history course at Aiea High School one summer, it turns out, did give me that excitement. I found that I loved the classroom and working with students. It gave me a sense of meaning I hungered for. But to learn that about myself, I had to take some time, I had to explore, and I had to pay attention to my own emotions and desires.”

Mike’s first teaching position was at Fordham University in the Bronx. A Jesuit institution with a deeply rooted social mission, Fordham was the perfect place to apply his formidable intellect to the types of broader civic questions that had always animated his learning. He thrived for 13 years as a professor, publishing two books and becoming a respected scholar of U.S. history and foreign relations, until reaching another pivotal decision that he calls the most difficult and most rewarding of his career: to move into administration as dean of the college.

Given his love of scholarship, this choice surprised many people around him. But as Mike had gradually become more involved in larger initiatives – whether as a member of the faculty senate or working on the university’s self-study for accreditation – he discovered that, “There were parts of me that were much happier dealing with these bigger questions about the mission of the institution, the goals of education, and how I was going to help advance those goals. Looking at a broad array of problems, engaging with a range of different people, thinking strategically … I discovered this was something I loved to do.”

Mike demonstrated his leadership ability as dean of Fordham’s College at Rose Hill and in 2014 accepted a post as vice president for academic affairs and dean of Grinnell College, a small liberal arts school with an equally strong commitment to questions of equity and social justice. Despite entering as a newcomer (his position had always been filled by candidates from within the faculty), Mike quickly became “by far the most respected and trusted person on campus, for faculty as well as students,” according to Grinnell’s chair of faculty, Professor Henry Rietz.

Students are hands down Mike’s inspiration. Every single issue for him, whether it’s about faculty, athletics, or governance, always comes down to what is going to best support student learning. He wants all students to be able to have the kinds of transformative experiences he did.

Jennifer Latham

Reflecting his own evolution as a student and teacher, Mike’s goal at the administrative level has always been to create educational experiences that awaken young people to their own personal sense of mission and purpose. As he reminded graduating students at Grinnell this year, “One of the greatest benefits of a liberal arts education is that, in a real and powerful way, it liberates you. Learning how to learn enables you to author your own life and to determine how you will respond to a world that sorely needs your energy, talents and compassion.”

His list of accomplishments in four short years at Grinnell is impressive, but there is one he singles out as particularly gratifying. “A lot of the research in education has shown that when students get involved in helping to create knowledge, it transforms their experience,” he explains. “They become far more invested in learning because they can actually see themselves contributing to and being an active part of discovery.”

The ambitious idea of facilitating a research experience for every single Grinnell student was initially met with skepticism, due to the sheer complexity of such a

systemic operational change. But Mike met individually with each of the college’s 26 departments before working through a series of intricate negotiations with the institution’s officials to ensure its financial viability. Today, every Grinnell student graduates having designed a significant research experience, mentored by a faculty member from their major.

“Students are hands down Mike’s inspiration,” says his wife, Jennifer. “Every single issue for him, whether it’s about faculty, athletics or governance, always comes down to what is going to best support student learning. He wants all students to be able to have the kinds of transformative experiences he did.”

“Mike’s leadership style is characterized by humility,” observes Rietz. “He’s a fantastic listener and collaborator, and he has a nurturing, ground-up approach that really gives people a sense that he values our campus culture, but also challenges us to look ahead and move forward. I think part of what makes him so effective is that, at heart, he’s a teacher. In a meeting, he’ll often begin by presenting some information or data, and then raise questions about what we should do to address the situation. Like an educator, he’s pursuing certain objectives, but he’s leading the group to

discover the solutions on their own.”

The Home Stretch

While the decision to leave higher education may seem like another unexpected turn in Mike’s career, those close to him understand just how much returning to Punahou means to him. Not only is it the place where his own educational journey began, but “Punahou’s sense of place, its grounding in Hawai‘i’s culture, tradition and history, is a force for distinctive excellence and a major part of what distinguishes it from other schools,” he says, adding that he has always felt most at home in Hawai‘i’s culturally diverse and unique natural setting.

Mike grows visibly animated when speaking of the opportunities to move education forward at the K – 12 level, pointing out that many of the challenges that colleges and universities are grappling with – from social, emotional and ethical learning to navigating an increasingly diverse and technologically disorienting world – can be better addressed when students are younger. Some of the most compelling opportunities, he emphasizes, are to be found in the work of the Junior School.

He is also adept at translating questions central to the educational enterprise into broader terms that reveal his philosophy of social change. When speaking about student diversity, for example, he explains that, “If education is really going to be an engine to address historical and structural inequalities in the United States, then you must create the most broadly representative kind of educational experience possible. You have to bring in people who have historically been underrepresented – for everybody’s benefit. This, to me, is one of the reasons why a school like Punahou could have a tremendous public impact.”

When tracing the arc of Mike Latham’s life, there is a clear thread that connects the intellectually curious and hard-working high-school student to the thoughtful leader who will be Punahou’s next president. While he no longer runs marathons, the distances he has crossed have transformed the remarkable resolve of that 12- year-old boy into a wholehearted dedication to his true calling.

“The education I received at Punahou prepared me very well for college,” Mike told faculty and staff gathered in Thurston Memorial Chapel to hear the news of his appointment. “But something deeper happened at Punahou, something that I think is really at the heart of the enterprise: I began to realize that the really important challenge I faced – and that I think every student faces – is not just to figure out what I was good at, but what I cared about, what I was willing to commit myself to. That required a process of reflection, discernment and serious soul searching that unfolded over time, but the answer to that question for me was education.”

“The big challenge for us as a school is designing the right educational experience to prepare our students for the world today and in the future,” said Punahou Trustee and Presidential Search Committee Chair Mark Fukunaga ’74 that same afternoon. “It is neither an easy nor predictable world, but one in which knowledge is becoming a commodity and disruption is the norm. Mike was the search committee’s unanimous choice to be Punahou’s next president, and we believe that he exemplifies the qualities of strategic leadership, intellectual innovation and community building that will shape the next era of Punahou’s history.”

Over the coming year, Punahou’s Trustees are committed to guiding this important change in leadership with attention and care. “The Board of Trustees looks forward to working with both President Jim Scott and President-elect Mike Latham and their families to assure a smooth transition,” says Punahou Trustee and Presidential Transition Committee Chair Connie Hee ’70 Lau. “As we prepare to welcome Mike, we will be also celebrating the work Jim has done to benefit a generation of Punahou students and position the School as a global thought leader for educational innovation and social responsibility. We invite our entire community – both in Hawai‘i and beyond – to join us.”