Novelist and editor Hanya Yanagihara ’92 doesn’t dabble. Her books are each genre-busting experiments that plunge readers into emotional maelstroms of moral ambiguity.

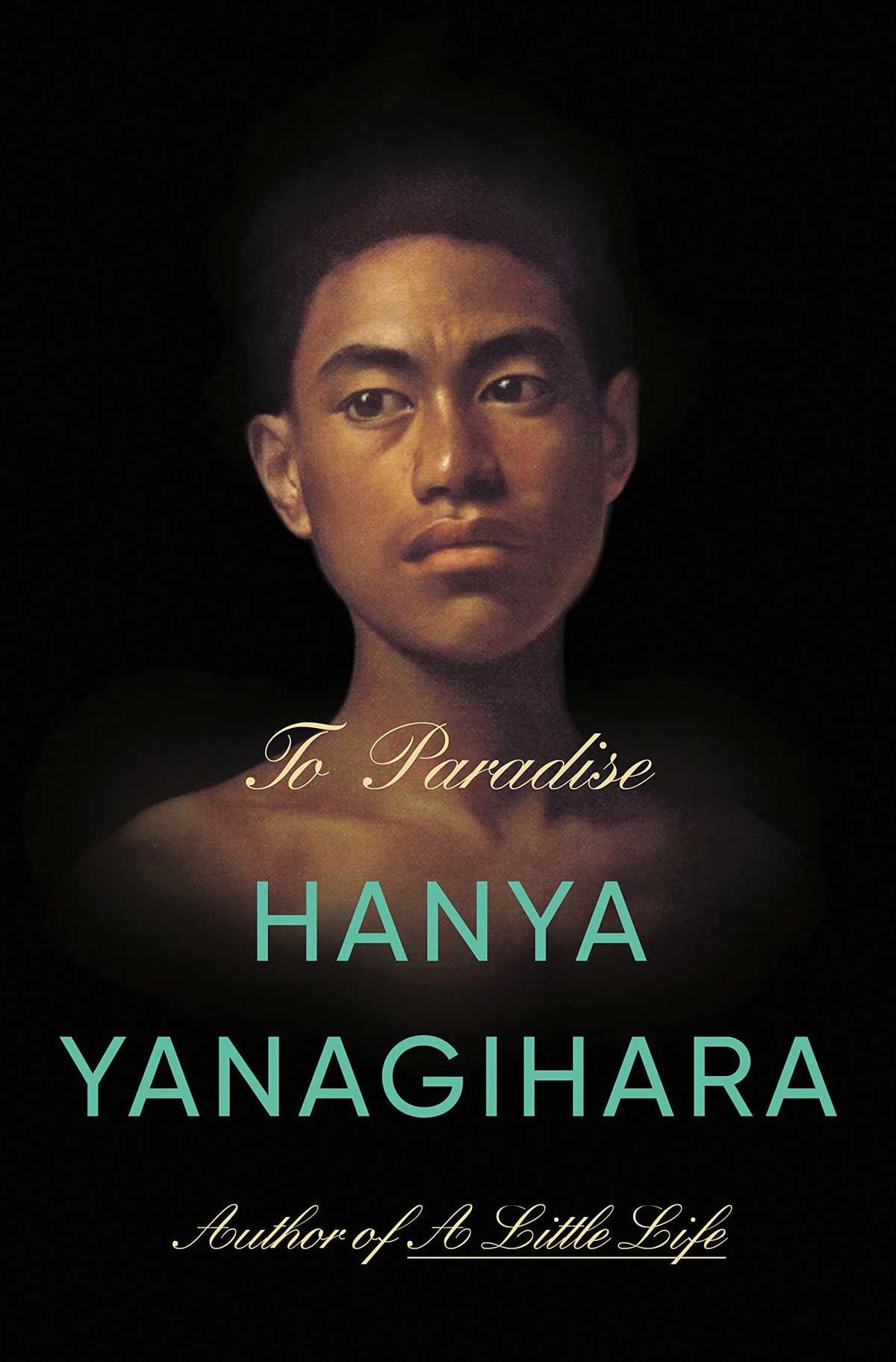

Doubleday paid more than $1 million for the rights to publish “To Paradise,” her third novel – which is really three books in one, set in alternate versions of New York three centuries apart. The 1893 version takes place in the fictional Free States, where people may – seemingly – love whomever they please. The 1993 thread follows a young Hawaiian man navigating the AIDS crisis, while the 2093 thread delves into a plague-riden future dystopia. She wrote much of it in Hawai‘i during the COVID-19 shutdown.

“I’m proud of it,” Yanagihara says. “I wanted to do something that felt hard and that felt challenging for me. I think every book should feel challenging in a different way.”

She has every reason to feel proud; “To Paradise” landed on The New York Times’ bestseller list in January 2022. It scored another big coup when former President Barack Obama ’79 put the book on his popular Summer Reading List 2022. Fellow author Edmund White declared it as good as “War and Peace.” This is hardly Yanagihara’s first brush with success.

Her preceding novel, “A Little Life,” hit the literary world like a stealth bomb in 2015. What starts as a story of four college friends, turns into a harrowing unveiling of the abuse suffered by one of the characters. New Yorker reviewer Jon Michaud praised the book’s “subversive brilliance,” but warned that “it can … drive you mad, consume you, and take over your life.” The Wall Street Journal called it “an epic study of trauma and friendship” – a benchmark against which all other books on the subjects will be measured.

While Yanagihara’s first novel, “The People in the Trees,” did well, the runaway success of the second was a surprise. “A Little Life” sold more than a million and a half copies in English, was shortlisted for both the Man Booker Prize and National Book Award, and won the 2015 Kirkus Prize. The author took it in stride, preferring to plot her own course rather than cater to her sudden cult-like following.

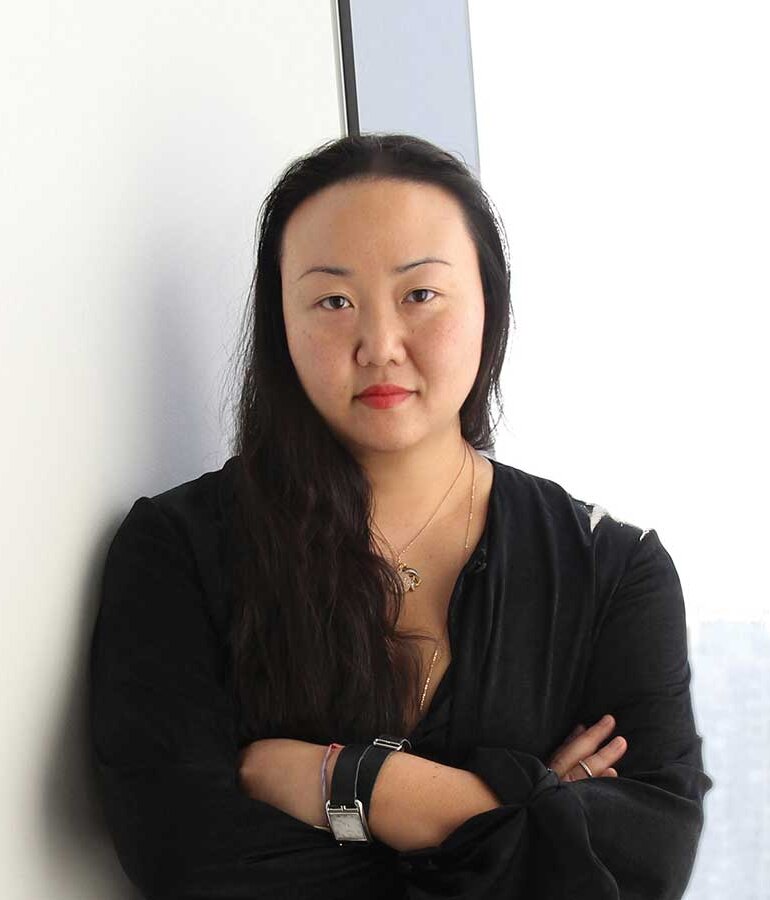

Yanagihara has a whiff of Garbo’s “I want to be alone,” mystery. She wears her hair parted down the middle – a steely look brightened by rosy lips and chunky gold jewelry. Her Manhattan apartment, featured in more than one magazine, reflects the same intensity punctuated by beauty. A double-sided bookshelf divides the one-room flat into private and public chambers. Artwork covers the living room walls floor-to-ceiling, with hot pink paint peeking through the gaps between the frames. The floors are glossy black.

Yanagihara settled in New York nearly three decades ago after a childhood of bouncing around. Her father, a physician who grew up in Hawai‘i, moved the family 15 times before Yanagihara entered high school. “If you move a lot, you learn that you can fit in,” she says. “You can make a life for yourself anywhere.”

But rural Texas proved rough for her as a ninth grader. Fed up with the racist bullying she experienced at school, Yanagihara told her parents: Send me to boarding school or back to Hawai‘i. Her parents agreed. She moved in with her grandparents in Hawai‘i Kai and enrolled in her father’s alma mater, Punahou.

“It felt like heaven getting back,” says Yanagihara. “It was revelatory to me that I was at a place where I could have friends, potentially go to prom, and not be tripped as I walked down the hallways. And if I were disliked, it would be for my personality and not my race.”

At Punahou, Yanagihara swam on the junior varsity team, worked in technical theater, and helped produce the school newspaper and yearbook. “It really felt in many ways more like a collegiate campus,” she remembers. “It was a place where you could spend all day.” She loved her teachers and the sophisticated curriculum. “We read a lot of contemporary British poetry – like Ted Hughes’ Crow – things that I would never have gotten into on my own.”

She moved to New York in 1995 after graduating from Smith College. She worked for a publishing house, then landed a job at Condé Nast Traveler, where she was the deputy editor and later editor-at-large. “I always knew I wanted to write,” she says. “I was always aware that it was an occupation.” Being on the receiving end of so many manuscripts taught her an important lesson. “It sounds so obvious, but it is never the most brilliant writers who get published,” she says. “It’s the people who finish.” Yanagihara is the rare writer who succeeds at both.

I wanted to do something that felt hard and that felt challenging for me. I think every book should feel challenging in a different way.”

– Hanya Yanagihara

Best-selling novels are merely her side-gig; in 2017 she became the editor-in-chief of T: The New York Times Style Magazine. Recently, the New Yorker gushed, “Thanks to her magpie intelligence, it has become a vibrant cabinet of curiosities.” The job came with a reliable – if rigorous – schedule and perks such as private museum visits and international travel.

As an international tastemaker, she gives voice and visibility to Asian Americans. Her job also affords her the opportunity to share Hawai‘i with the world. One of her star writers, Ligaya Rogers ’88 Mishan, is a fellow Punahou grad who pens thoughtful articles that reference Asian and Pacific Island culture. “I call her pieces ‘Trojan horse stories,’” says Yanagihara, “because they seem like they’re about a particular topic, and they’re actually about the great injustice and inequalities in the capitalist society and the food chain.” Yanagihara and Mishan have teamed up on stories about taro, crack seed and cooking with invasive species.

During the pandemic, Yanagihara produced a series of stories about how art and culture in general have responded to past plagues. “We did a really great story about posies – those little bouquets that people carried during the Black Death just to smell. The idea was that vapors would ward off the disease,” she says. Another article explored the loss of the European kiss. “If the double kiss becomes a thing of the past, what does it mean when certain cultural totems start disappearing because of health?”

When COVID-19 first emerged and her staff was sent home, they happened to be working on a travel issue dedicated to the Silk Road. “It was a very moving experience for me to edit that issue in the early stages of the pandemic,” she says. “To realize how frightening this road must have been for its travelers – they had very little protection, and there were many dangers along the way. And yet, they endured. You realize that even during the worst pandemics, trade continued, art kept being made, and the world kept moving forward.” It’s a lesson she took to heart, adding her own chapters to the human story.